Naem Mufarreh DO1, Jaron Lohmeyer DO1, Alex Davis OMS-IV2, Charles Spieser DO1, Michael R McDermott DO1, Natalie Bauer MD1,3

1Kettering Health Grandview Orthopedic Surgery, Dayton Ohio

2Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, Athens, Ohio

3Orthopedic Associates of Southwest Ohio, Dayton Ohio

DOI: 10.70709/TS8759-RF

Abstract

The intraoperative discovery of hyperpigmented bone is a rare and poorly documented phenomenon with limited literature to guide diagnosis and management. While the most reported cause of osseous hyperpigmentation is long-term minocycline use, other potential etiologies include ochronosis from alkaptonuria, injury-related sequestrum, metallosis from implants, and metastatic disease. Accurate identification of the underlying cause is critical, as certain conditions may compromise bone structural integrity and impair healing.

We report a case of a 34-year-old female presenting with left wrist pain diagnosed as Kienböck’s disease. Intraoperatively, her carpal bones and distal radius exhibited a striking purplish-blue pigmentation. This case highlights the need for a systematic approach to intraoperative bone hyperpigmentation, including thorough medication and family history reviews, metabolic disorder testing, and consideration of metastatic disease. We outline a differential diagnosis and diagnostic options for evaluating patients with intraoperative bone discoloration to guide future surgeons in decision-making when they come across this rare phenomenon.

Keywords: Blue, pigmented, bones, differential, diagnosis

Introduction

Intraoperative discovery of hyperpigmented bone is a rare occurrence with limited literature and case report documentation. Literature reviews revealed that the most reported cause of osseous hyperpigmentation is long-term minocycline use. Other differential diagnoses of hyperpigmented blue-grey or black bones include ochronosis secondary to alkaptonuria, injury related sequestrum, metallosis from implanted material and metastatic disease. It is important to find the etiology of bone hyperpigmentation because the structural integrity of the bone could be compromised, and the ability of the bone to heal could be inhibited (1).

Case Report

A 34-year-old female presented for an initial evaluation of left wrist pain. Her past medical history included asthma, ADHD, anxiety/depression/bipolar. She is a lifelong nonsmoker. Past surgical history included diagnostic right ankle arthroscopy with peroneal tendon corticosteroid injection in 2014, Colectomy in 2016, and bilateral carpal tunnel releases in 2022. Her medications include dextroamphetamine-amphetamine, bupropion, albuterol, fluticasone proprion-salmeterol, Famotidine, and escitalopram. She has no history of minocycline or tetracycline use per chart review. Her family history includes hypertension in her mother, hyperlipidemia and heart disease in her paternal grandfather.

Two months prior to her orthopedic evaluation the patient had an oncology evaluation due to leukocytosis. Oncology opinion was mild, intermittent leukocytosis due to intermittent, mild neutrophilia and mild eosinophilia. Hemoglobin and platelet counts have been normal. Further testing included FISH for BCR-ABL which was normal, and repeat CBC and Smear review were unremarkable. The oncologist stated that “there is no strong indication for a more aggressive evaluation, including a bone marrow biopsy.”

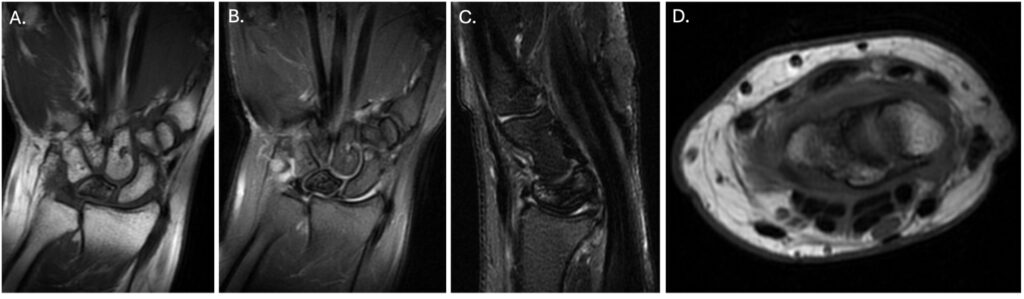

Radiographic imaging studies of the left wrist demonstrated normal intercarpal alignment, normal metacarpal alignment, and negative ulnar variance (Figure 1). There was no evidence of any fractures, and without evidence of CMC dislocation. No evidence of bony lesion or soft tissue abnormalities. An MRI of the left wrist was compromised secondary to motion, but it demonstrated cystic degeneration consistent with avascular necrosis of the scaphoid, confirming the diagnosis of Kienbock’s disease (Figure 2). There was a deformity of the proximal aspect of the lunate with what appeared to be a step off deformity at the lunate face of the radius. There was no ligament or tendon abnormality.

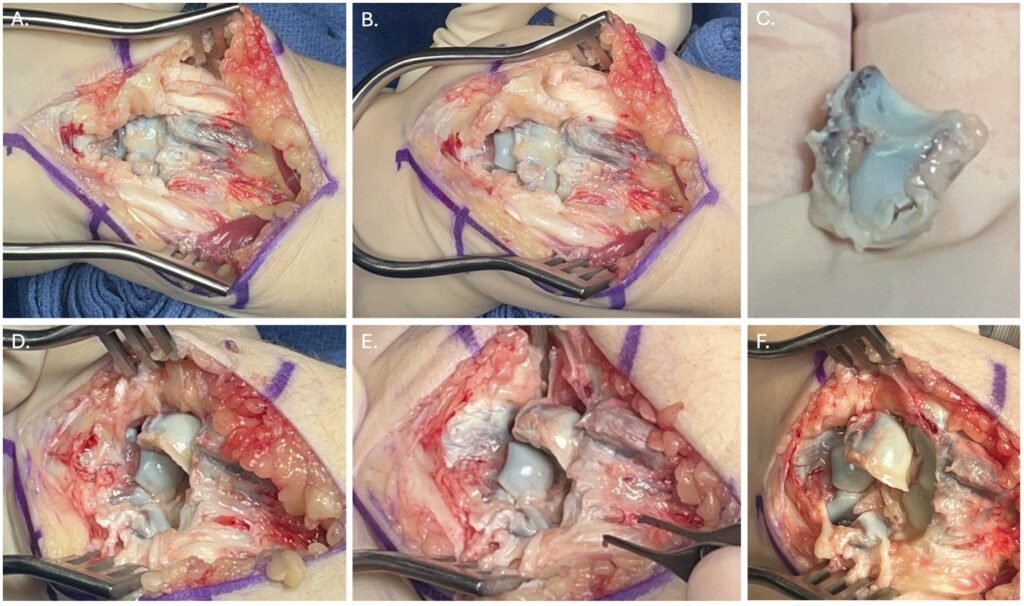

Physical examination featured pain with terminal wrist flexion and extension as well as gripping objects and load/weightbearing. After failure of nonoperative treatment including physical therapy, the patient was scheduled for left wrist denervation, lunate excision with scaphocapitate fusion. Intra-operatively the articular surface and periosteum of all carpal bones as well as the distal radius surfaces appeared purplish/blue. Specimens were sent intra-operatively for histological examination. Histological examination of the lunate of the left wrist bone featured avascular necrosis, consistent with clinical impression of Keinbock’s disease, with no other noticeable abnormalities. Decalcification was performed on this bone sample. During surgery the intra-medullary canal of the lunate was examined and found to be necrotic. The surgeon had concerns for the health of the carpal bones and a failure of healing if a scaphocapitate fusion was performed so a proximal row carpectomy was performed.

Four months after surgery, the patient is doing well, has no post-operative complications, and the radiographic images are shown in Figure 4. The patient is currently in the process of being worked up for an underlying cause of the pigmentation.

Discussion

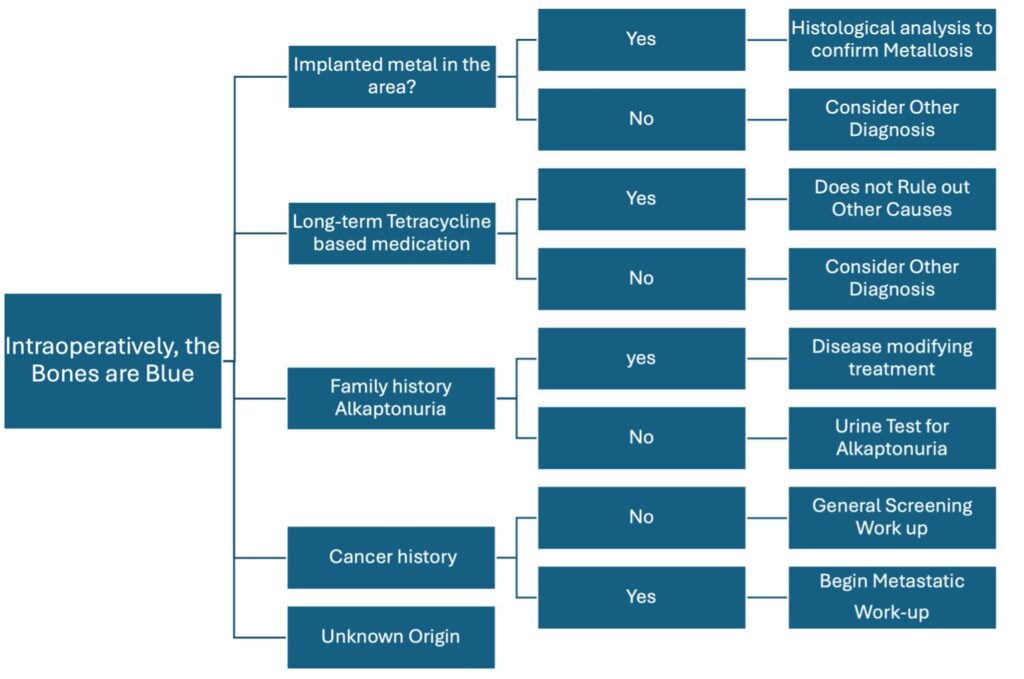

To date, there are no clear papers that help describe the differential diagnosis for when blue pigmentation is seen intraoperatively and the next steps to consider. While the exact cause in this case has not yet been identified, the authors of this paper felt it was necessary to share the current findings with the community and help define a path for surgeons to follow when this is encountered. The differential diagnosis of blue or black bone hyperpigmentation includes ochronosis secondary to alkaptonuria, injury related sequestrum, metastatic disease, and long-term minocycline or tetracyline use (1).

Ochronosis is a condition that causes bone hyperpigmentation from alkaptonuria (AKU). An autosomal recessive mutation resulting in the accumulation of polymerized homogentisic acid (HGA) from a deficiency of homogentisate 1,2 dioxygenase (HGD) activity. The accumulation of HGA can cause destruction of connective tissue resulting in joint disease. Diagnosis can be made with a urine test, if a patient’s urine is alkalinized or allowed to stand the homogenstisic acid metabolizes to a melanin-like substance and the urine will appear brown or black (5). Family history or personal history of early-onset osteoarthritis can also raise suspicion for AKU in patients.

Minocycline, a semi-synthetic tetracycline antibiotic, turns black when oxidized, causing discoloration of the skin, lips, nail, teeth, bones, and other visceral structures (1,2). Minocycline-induced bone pigmentation does not have any impact on bone healing capability (3). Patient history of Tetracycline-class antibiotics does not exclude other causes such as metastasis. (6, 7).

Suwannarat et al. in 2004 published a case study with 5 patients that presented with pigmentary changes of the ear and degenerative changes in the spine and large joints. They were diagnosed with alkaptonuria, but they had normal urine HGA levels. It was reported that all five patients had a history of extended minocycline use for rheumatologic and dermatologic disorders (4).

We suggest a prospective differential diagnosis if blue pigmented bones are found intraoperatively (figure 5).

Conclusion

When hyperpigmented bones are found intraoperatively a detailed history and clinical examination should be performed in a retrospective fashion. A full medication history should be obtained and evaluated. Specifically, the use and duration of tetracycline-class medications should be discussed. Physical examination may reveal pigmentation of dentition or skin. Recent injuries or trauma to the affected area should be evaluated. Family history questioning should include metabolic disorders like alkaptonuria and consider offering the patient a diagnostic urine test. A metastatic work-up including CBC, CMP, and chest x-ray should be included. If metastatic work-up is suggestive, bone scan and other radiologic evaluation should be considered. A perioperative histological examination where focal pigmentation is present should be included for possible bony metastatic disease.

References

- McCleskey,PE, Littleton KH. Minocycline-induced blue-green discoloration of bone. J Bone Joint Surg. 2004;86(1):146-148.

- Rumbak, M. J., Pitcock, J. A., Palmieri, G. M., & Robertson, J. T. (1991). Black bones following long-term minocycline treatment. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine, 115(9), 939–941.

- Chubb DWR, Finkemeyer JP, Bush KL. Etiology of Craniofacial Bone Hyperpigmentation and an Algorithm for Addressing Intraoperative Discovery. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8(8):e3061. Published 2020 Aug 17. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000003061

- Suwannarat P, Phornphutkul C, Bernardini I, Turner M, Gahl WA. Minocycline‐induced hyperpigmentation masquerading as alkaptonuria in individuals with joint pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(11):3698‐3701

- Aquaron R. Alkaptonuria: a very rare metabolic disorder. Indian J Biochem Biophys. 2013;50(5):339‐344. Web of Science.

- Hilton HB. Skeletal pigmentation due to tetracycline. J Clin Pathol. 1962;15:112–115.

- Rall, D.P., Loo, Ti Li, Lane, M., and Kelly, M.G. J. Nat. Cancer Inst,. 1957; 19, 87