Steven Bennett, DO1; Brendan Kelly, OMS-III2; Madison Messmer, DO1; Samuel Shepard, DO1; Gavin Scott, DO1; Michael R. McDermott, DO1; H. Brent Bamberger, DO1

1Kettering Health Grandview Orthopedic Residency, Dayton, Ohio

2Des Moines University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Des Moines, IA, USA

DOI: 10.70709/85TR-9123

Background

Leadership is a critical element in achieving both personal and professional success, particularly in healthcare where team collaboration is essential. A strong leader who can effectively communicate, assign roles, and delegate responsibilities is often the driving force behind a successful team. However, leadership skills are notably lacking among frontline physicians, largely due to the insufficient emphasis on leadership development in medical training. Some programs have begun incorporating leadership training for their residents and students, finding it valuable, recommending other programs to adopt similar initiatives.

Purpose

To standardize leadership training in medical education, we first must distinguish leadership from management. With this in mind, the purpose of this study is to define leadership in the clinical setting, and assess how medical trainees perceive it and its potential integration into their training.

Methods

A survey was sent to residents of a community-based training hospital. The de-identified survey consisted of 10 multiple-choice and multiple-answer questions defining leadership, interest in leadership training, confidence in personal leadership, and perceived necessity for formal leadership training. Demographics such as year in training, specialty, and gender were also collected for analysis. Data was collected and analyzed through SurveyMonkey.

Results

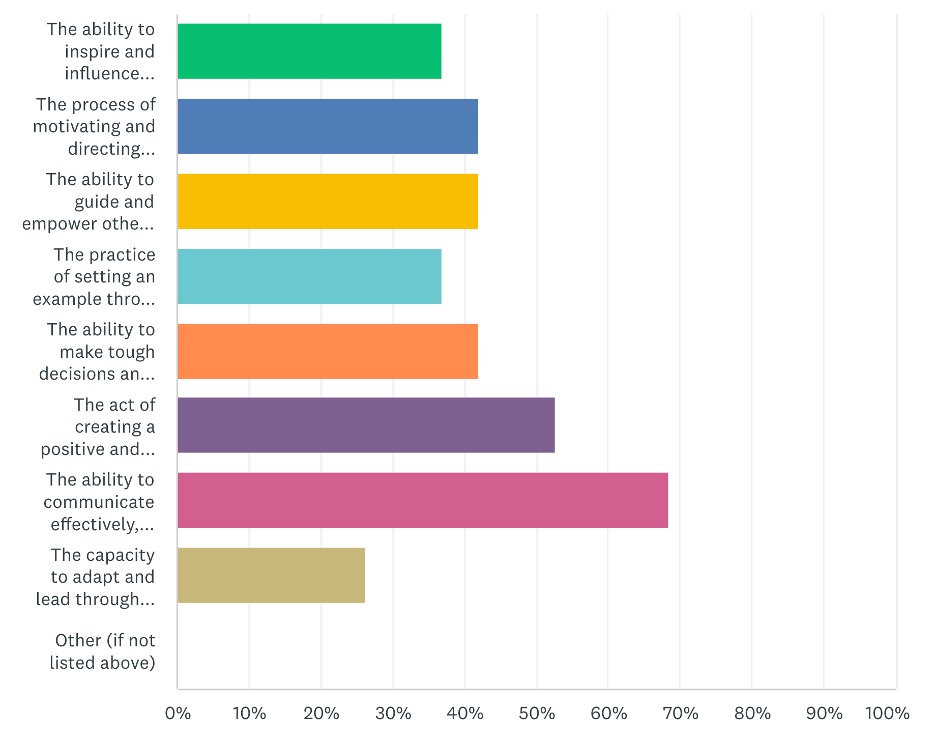

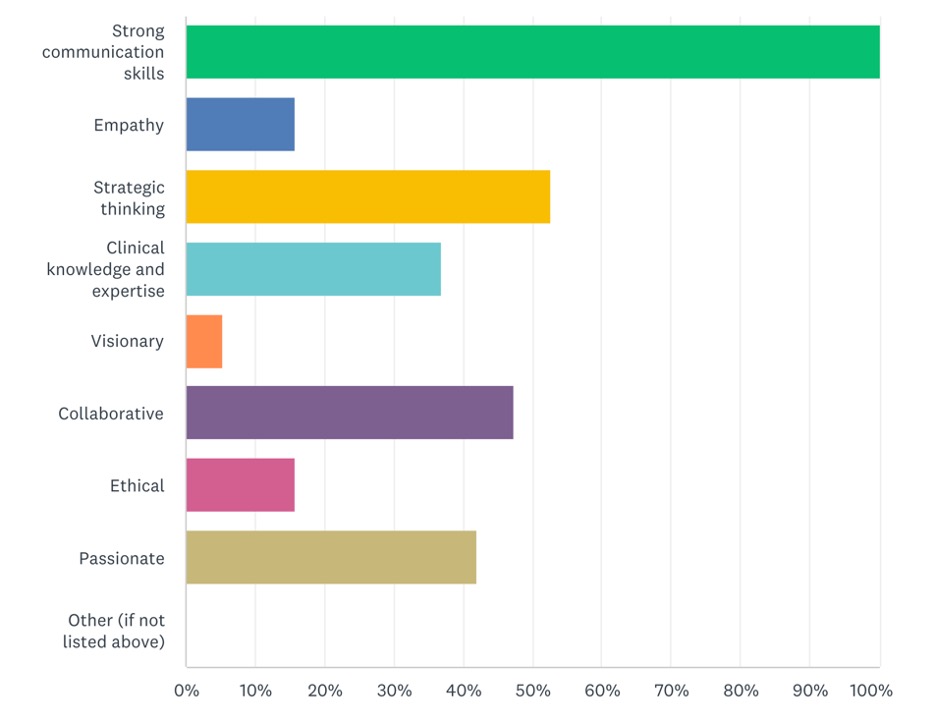

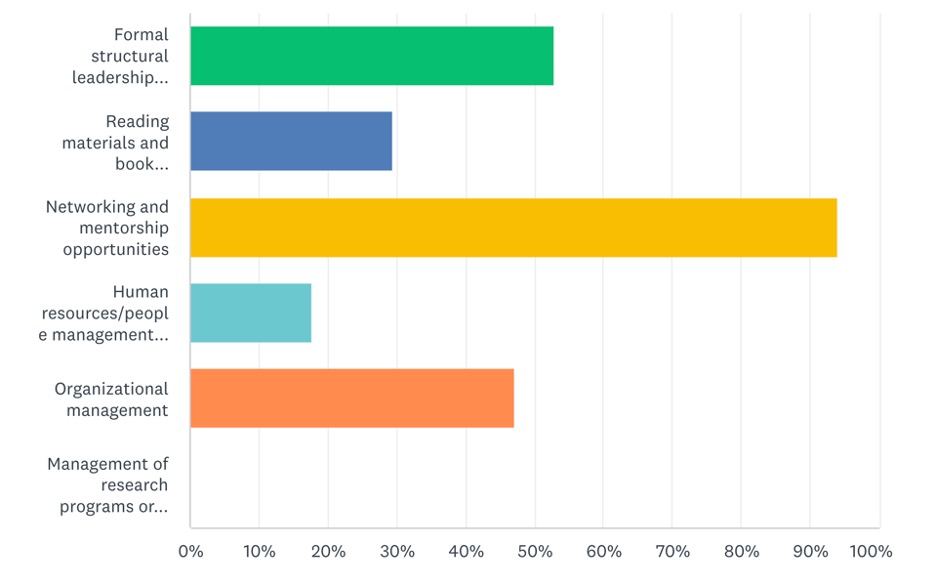

Twenty-one (21) responses were received, consisting of eleven (11) male and ten (10) female participants. The respondents ranged from first postgraduate year (PGY-1) residents to those finishing their residency (PGY-5), with the largest number of respondents in postgraduate year 3. The specialties with the highest number of responses were Family Medicine and Orthopedic Surgery , each accounting for 19% of total respondents. 100% (21/21) of respondents stated some attending physicians were better leaders than others, with 66.7% (14/21) stating the most important characteristic of these leaders is the ability to communicate effectively, listen actively, and build strong relationships with others. 24% (5/21) of respondents stated they did not believe medical school and residency alone prepared them to be adequate leaders with 43% (9/21) stating leadership training should be incorporated into residency programs and 24% (5/21) stating leadership training should be incorporated into all phases of medical training, including as attending physicians.

Conclusions

Nearly all respondents agreed that leadership training should be a part of medical education, with over half emphasizing its value in improving networking and mentoring in their roles as physicians. Respondents highlighted communication and relationship-building as key leadership traits, and noted their medical education lacked direct preparation in these areas. Leadership skills are vital for success in healthcare, and should be prioritized in medical training.

Keywords: Leadership, Medical Education, Leadership skills, Communication, Residency

Introduction

Leadership skills are an integral component in the development of personal and professional success. Multiple factors make a healthcare team successful, and the majority stem from having a strong leader who can efficiently communicate and delineate roles and responsibilities. Effective physician leadership improves patient outcomes by creating a collaborative work environment, promoting safe clinical practices, and facilitating the development of skills and outcomes (1). Leadership skills benefit patient outcomes, and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 presumes that physicians have the necessary leadership and managerial skills to operate a functional clinic (2). In addition to this, the American Council for Graduate Medical Education has identified the competencies of professionalism, systems-based practice, and communication as crucial aspects of physician training (3). Growing evidence shows that a dearth of any of these domains may result in patient harm(4).

Despite this fact, there is a severe lack of leadership skills in frontline physicians that can be attributed to numerous reasons, the most important being that leadership training is simply not incorporated enough into the medical curriculum (1). If the medical field is to move the needle for leadership, we must get away from the notion of physicians being “accidental leaders” and towards the deliberate action of leading (5). The most effective way of doing this is through systematic leadership training (6). Current literature on the topic provides evidence that leadership development training helps organizations achieve their goals through performance enhancement and successful planning (7,8). For leadership training to gain popularity among residency and medical school curricula, a common definition of leadership must be met. This definition must be both actionable and measurable for formal training to hold the greatest efficacy. Among leadership literature, substantial heterogeneity remains when defining and measuring leadership in the medical field (6). This has led to an equally detrimental heterogeneity when it comes to leadership training programs. Objectivity is particularly lacking in training assessments which may contribute to the failure of its widespread adoption (6). Most analyses of training success have relied on surveys sent to participants assessing their changed opinions of personal leadership attributes (6). The subjectivity of these findings begs the question of their robustness. Fortunately, some, such as the VHA Coaching and Leadership Initiative, have set examples of how success can be objectively quantified through disease management and patient satisfaction(9).

Despite physicians inherently being put into leadership roles in both residency and as attending physicians, leadership training is not a formal requirement for trainees. Leadership skills vary among medical residents and attending physicians which directly impacts patient care and medical teams. The authors sought to understand the thoughts of medical residents/fellows on leadership training and if they felt that this should be incorporated into their education. The findings of this study may function as a call for residencies and medical schools to invest in formalized interdisciplinary leadership training as an effective model for improved patient outcomes.

Methods

This study was found to be exempt by our International Review Board. In March of 2023, a survey was sent via email to all residents at our institution, consisting of 10 multiple-choice and multiple-answer questions defining leadership, interest in leadership training, confidence in personal leadership, and perceived necessity for formal leadership training. Demographics such as year in training, specialty, and gender were also collected from the survey. Data was collected and analyzed through SurveyMonkey.

Results

Twenty-one (21) residents responded to the survey from 9 different specialties: Anesthesia, Emergency Medicine, Diagnostic Radiology, Internal Medicine, Family Medicine, General Surgery, Neurology, Obstetrics and Gynecology, and Orthopedic Surgery. Most responses were from residents in their third year of training (9), male (11), and either in orthopedic surgery (4) or family medicine (4) training. When asked to define leadership in a clinical setting, most 66.7% (14/21) chose the ability to communicate effectively, listen actively, and build strong relationships with others [Figure 1]. This emphasis on communication skills was echoed when participants were asked to describe defining characteristics of leading attendings within their residency [Figure 2].

All responses indicated that some attending physicians in their residency were better leaders than others. 47.6% (10/21) either disagreed or strongly disagreed when asked if medical school and/or residency had adequately prepared them for leadership roles. While most reported the current state of medical school and residency curriculum as inadequate in preparing physicians to lead, responses indicated that formal training in the way of networking and mentorship opportunities would likely be efficacious [Figure 3]. 24% (5/21) of respondents stated they did not believe medical school and residency alone prepared them to be adequate leaders, with 43% (9/21) stating leadership training should be incorporated into residency programs and 24% (5/21) stating leadership training should be incorporated into all phases of medical training, including as attending physicians.

Almost all respondents (20/21) believed that they understood what it means to be a leader of a team or community. 90.5% (19/21) of the respondents perceived themselves as leaders among their peers and patients. Only two (9.5%) believed that medical school and/or residency adequately prepare physicians for the leadership responsibilities bestowed upon them as attending physicians. To prepare for these leadership roles, two (9.5%) responded that formal leadership training should be provided during medical school only, eight (38.1%) indicated training should be during residency alone, and seven (33.3%) believed that training belongs in medical school, residency, and independent practice. Two (9.5%) respondents do not see formal training as a beneficial use of their time in medical school, residency, or independent practice.

Discussion

Formal leadership development training programs are proven modalities for improved patient outcomes as well as physician self-assessed knowledge and expertise (6,9). However, the current degree of heterogeneity among assessed outcomes begs the question of generalizability. If we are to approach a level of standardization in leadership training programs we first must define leadership and discern it from management. Often, literature on leadership uses the terms management and leadership synonymously, however, this ignores the reality that not all who find themselves in explicit managerial positions are adequate leaders. The definition defined by our survey parallels that of Kumar et al. in that leadership is the ability of an individual to guide a group toward a common goal. Leaders, in contrast to managers, tend to motivate through the use of words and actions rather than the use of financial incentives or punishment to reign control over subordinates (10). Our survey found that attending physicians who are perceived as stronger leaders were often more skilled in their communication and listening.

As depicted by our survey, the desire of current medical residents to receive formal leadership training is growing. Nearly all of the respondents to our survey indicated that leadership training would be a benefit to their medical curriculum. We believe that a gauge of interest is essential prior to the initiation of a leadership training program. The reason for this is that the participants must be prepared to implement the skills learned in their training in their everyday practice. While our collection of resident physicians indicated a high degree of interest in formal training, this desire for training may not be shared by more seasoned attending physicians. One of the greatest limitations of current leadership literature is the lack of objective outcome assessment to legitimize their findings (6). Most leadership development curriculum claims to be transformative for healthcare and capable of quantifiably improving patient outcomes, yet these outcomes are not measured (6,10,11). Increasing busy physicians’ desire to invest both time and energy into formal training is going to require evidence of the training’s efficacy. Fortunately, examples of objectivity in training programs have been published, such as Whitman’s analysis of skills and knowledge in chief surgical residents after seminar and lecture sessions (12).

Every orthopedic surgeon has been shaped by a mentor who demonstrated exceptional leadership, yet not every surgeon takes the step to become a great leader themselves. Leadership in orthopedics demands more than technical skill; it requires clear and empathetic communication, emotional resilience, and an unwavering commitment to putting others—colleagues, staff, and patients—first. These traits are not optional; they are essential.

As orthopedic surgeons, we are inherently placed in positions of influence as we advance in our careers. Embracing and refining our leadership skills is not just an opportunity—it is a responsibility. Strong leadership fosters better patient outcomes, cultivates healthier work environments, and transforms hospital culture. There is a need to address the current state of of leadership training.

One of the questions that remains unanswered is whether leadership training should begin in medical school or residency. All of the studies assessed within this review discussed training programs for resident physicians and/or attending physicians, not medical students. While many medical schools are beginning to incorporate interdisciplinary leadership training into their didactic years curriculum, there is a paucity of literature analyzing its effect on patient care. To answer this question of when to begin training more comparative analyses are required.

The current study is not without its limitations. We were limited in the number of responses which diminished our quality of evidence. In addition to this, all responses were from residents, decreasing the intended diversity of added medical students and attending physician opinions. Confirmation with larger, more diverse respondents is warranted to increase the quality of evidence. To our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind where medical trainees were asked their definition of leadership and what traits leaders within their program possess. This is an important addition to the body of leadership training literature due to the current heterogeneity in leadership definitions and the lack of evidence supporting various definitions.

Conclusion

The purpose of this survey was to understand the way medical trainees think about leadership, if and how it can be incorporated into training, and if they feel they have adequate leadership skills. Nearly all respondents stated they believe leadership training should be incorporated into the medical curriculum. Over half stated the most important skill they would like to learn is being able to network and mentor others effectively. All respondents believed certain attending physicians were better leaders than others and stated this was primarily due to their ability to communicate and develop positive relationships with others. Strong leadership is an essential component of an orthopedic surgeon, and there needs to be a stronger emphasis on leadership medical training.

References

- Blumenthal DM, Bernard K, Bohnen J, Bohmer R. Addressing the leadership gap in medicine: residents’ need for systematic leadership development training. Acad Med. 2012;87(4):513-522. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31824a0c47

- Bohmer R. M. (2010). Managing the new primary care: the new skills that will be needed. Health affairs (Project Hope), 29(5), 1010–1014 https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0197

- Moore JM, Wininger DA, Martin B. Leadership for All: An Internal Medicine Residency Leadership Development Program. J Grad Med Educ. 2016 Oct;8(4):587-591. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-15-00615.1. PMID: 27777672; PMCID: PMC5058594.

- Rosenstein, A. H., & O’Daniel, M. (2008). A survey of the impact of disruptive behaviors and communication defects on patient safety. Joint Commission journal on quality and patient safety, 34(8), 464–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34058-6

- Collins-Nakai R. (2006). Leadership in medicine. McGill journal of medicine : MJM : an international forum for the advancement of medical sciences by students, 9(1), 68–73.

- Frich, J. C., Brewster, A. L., Cherlin, E. J., & Bradley, E. H. (2015). Leadership development programs for physicians: a systematic review. Journal of general internal medicine, 30(5), 656–674. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-3141-1

- Burke MJ, Day RR. A cumulative study of the effectiveness of managerial training. J Appl Psychol. 1986;71:232–45. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.71.2.232.

- Collins DB, Holton EF., III The effectiveness of managerial leadership development programs: a metaanalysis of studies from 1982 to 2001. Hum Resour Dev Q. 2004;15:217–48. doi: 10.1002/hrdq.1099.

- Green PL, Plsek PE. Coaching and leadership for the diffusion of innovation in health care: a different type of multi-organization improvement collaborative. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2002 Feb;28(2):55-71. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(02)28006-2. PMID: 11838297.

- Kumar, B., Swee, M. L., & Suneja, M. (2020). Leadership training programs in graduate medical education: a systematic review. BMC medical education, 20(1), 175. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02089-2

- Straus, S. E., Soobiah, C., & Levinson, W. (2013). The impact of leadership training programs on physicians in academic medical centers: a systematic review. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 88(5), 710–723. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828af493

- Whitman N. (1988). A management skills workshop for chief residents. Journal of medical education, 63(6), 442–446. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-198806000-00003