John Petrucci, OMS-IV1; David Beckett, DO1; Cornejo Ochoa, DO1; Craig T. Gillis, DO2

1Western University of Health Sciences College of Osteopathic Medicine of the Pacific-Northwest, Lebanon, OR

2Summit Orthopaedics, Lake Oswego, OR

DOI: http://doi.org/10.70709/0apjf0g0cd

Abstract

Case

Scapular winging is a shoulder disorder that results in the prominence of the scapula’s medial or lateral border leading to pain, loss of strength, and cosmetic irregularities. The most common type is medial scapular winging, caused by damage to the long thoracic nerve and dysfunction of the serratus anterior muscle. We present a case of postoperative medial scapular winging from a long thoracic nerve palsy in an 18-year-old female with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) after an arthroscopic Bankart repair and capsulorrhaphy for chronic shoulder instability.

Conclusion

We postulate that multiple factors, including an interscalene nerve block, intraoperative shoulder traction of 10 pounds, and inherent joint hypermobility secondary to EDS, either acting in combination with additive effects or independently contributed to this patient’s long thoracic nerve injury. Understanding the potential for altered shoulder mechanics in EDS patients is crucial for developing preventive strategies and optimizing outcomes in patients with hypermobility disorders.

Keywords: Medial scapular winging, long thoracic nerve palsy, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, interscalene block, postoperative arthroscopic neuropraxia

Introduction

Scapular winging is a relatively rare shoulder disorder that results in the prominence of the scapula’s medial or lateral border, leading to pain, loss of strength, loss of range of motion, and cosmetic irregularities (1). It occurs due to dysfunction of the dynamic stabilizing muscles that attach the scapula to the thorax (2). Various types of scapular winging exist. The most common type is medial scapular winging, resulting from damage to the long thoracic nerve (LTN) and dysfunction of the serratus anterior muscle (2,3). Lateral scapular winging is rarer and occurs from trapezius muscle dysfunction following spinal accessory nerve injury (3). Several causes of scapular winging have been reported, primarily involving traction, compression, or iatrogenic injuries to the long thoracic or spinal accessory nerves (1,2,3).

Patients with scapular winging tend to complain of vague posterior shoulder and neck pain with gradual development of winging (1,3,4). Patients may also develop complaints of shoulder instability and loss of shoulder abduction (2). Due to the vague nature and variety of presenting symptoms, a detailed history including sporting activities, surgical history, history of trauma, and medical conditions such as hypermobility disorders and thorough physical examination are an essential first step in diagnosing scapular winging. Physical examination should be done with complete visualization of the patient’s back for an obvious deformity. Winging can be exaggerated by having the patient flex their arm forward and limiting abduction to 90 degrees. Isolated serratus anterior strength can be assessed by having the patient perform push-ups with winging revealed immediately or after fatigue following 5-10 push-ups (5). Isolated strength testing of the trapezius can be performed by having the patient perform shrugs. Differentiating posterior instability from scapular winging can also be assessed by the elevation and external rotation tests (5). According to Meininger et al., persistent scapular winging with the shoulder flexed to 90 degrees with external rotation suggests complete paralysis of the serratus anterior muscle (5).

We present this case of postoperative medial scapular winging with a long thoracic nerve palsy in an 18-year-old female following arthroscopic Bankart repair and capsulorrhaphy for chronic shoulder instability. We explore the interplay of preexisting hypermobility due to Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), intraoperative shoulder traction, and preoperative interscalene nerve block as potential contributors to medial scapular winging.

Statement of Informed Consent

Informed consent for publication of this case report and associated images was obtained from the patient.

Case Presentation

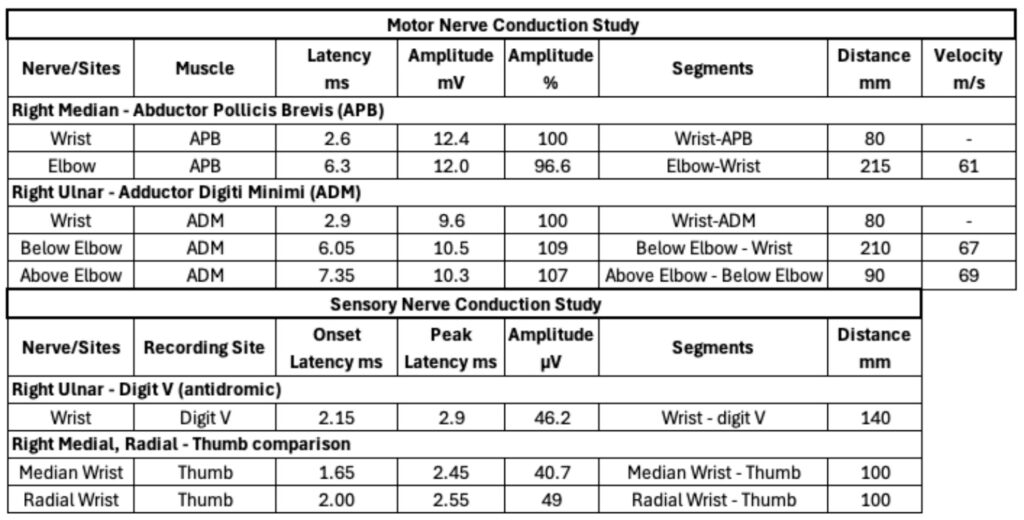

An 18-year-old female with EDS underwent arthroscopic Bankart repair with capsulorrhaphy in November 2021 for recurrent atraumatic shoulder instability. The surgery was performed in the lateral decubitus position with 10 lbs of longitudinal traction. The patient noticed scapular winging in March 2022 after rehabbing her shoulder with physical therapy over the previous four months. At her nine-month post-op visit in August 2022 she was noted to have scapular winging. She was advised to continue with physical therapy focusing on scapular biomechanics and serratus anterior strengthening. A nerve conduction study (NCS) and electromyography (EMG) were performed to evaluate for LTN injury in May 2023. The NCS revealed no abnormalities in motor or sensory conduction at the medial, ulnar, or radial nerves (Table 1). The EMG portion of the test revealed 3+ fibrillation potentials, positive sharp waves, and some polyphasic motor units at the serratus anterior muscle consistent with a LTN palsy. The patient was subsequently evaluated by neurosurgery in August 2023. They explained to the patient that a majority of injuries resolve within two years, but a small percentage do not experience full resolution. It is not noted what specific surgery they discussed with the patient, but they recommended repeating NCS/EMG in March 2024 and continuing physical therapy prior to further pursuing surgical intervention. There was no follow up visit with neurosurgery found in the notes reviewed. The patient’s last visit with physical therapy was in December 2023 and at that time her Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) questionnaire revealed a disability/symptom score of 56.82 out of 100, with lower scores signifying lower disability.

Table 1. Upper extremity nerve conduction study conducted approximately 18 months post-op. The sensory and motor portions of the study revealed normal onset latency, peak latency, amplitude, and conduction velocities.

The patient presented to our clinic in May 2024 for a second opinion of her ongoing shoulder and periscapular pain and right medial scapular winging. On physical examination, the surgical incisions were well healed and there was no obvious clinical atrophy of the shoulder girdle musculature. Active external rotation was limited to 50 degrees with her arm at her side. She demonstrated appropriate shoulder abduction to 160 degrees and forward flexion to 170 degrees while standing. Special testing demonstrated equivocal apprehension without sulcus sign or load and shift appreciated. The wall push-off test displayed obvious medial scapular winging. There was no glenohumeral instability. She was neurovascularly intact distally bilaterally. Right shoulder radiographs collected on the day of the visit showed no fractures or arthritic changes. Previous drill holes were noted at the anterior aspect of the glenoid.

A repeat NCS/EMG was obtained in May 2024 to assess neuromuscular healing. The updated study showed no evidence of ongoing acute nerve denervation, and the LTN showed disorganized volitional motor units with early recruitment consistent with motor unit reorganization. Given reinnervation patterns seen on repeat NCS/EMG, we decided to continue with physical therapy in June 2024 to improve scapular biomechanics and strengthen the serratus anterior muscle, with a plan to reevaluate symptoms in 6-12 months. However, the patient has not returned for follow-up.

Discussion

We propose that multiple factors, including an interscalene nerve block, intraoperative shoulder traction of 10 pounds, and inherent joint hypermobility secondary to EDS, either acting in combination with additive effects or independently contributed to this patient’s LTN injury. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for developing preventive strategies and optimizing patient outcomes.

The patient’s interscalene block may be a critical factor in her development of scapular winging. A study of 197 long thoracic nerve palsy cases found that 22 began after locally invasive procedures such as first rib resection and mastectomy with axillary dissection, and 10 cases began after anesthesia, likely related to arm positioning, but none of which described a postoperative arthroscopic neuropraxia (6). A meta-analysis investigating complications following peripheral nerve blocks by Sondekoppam et al. found that long-term adverse effects are rare, occurring between 2.4-4 in 10,000 blocks, but short-term adverse events lasting up to two weeks occur more frequently at rates of 8.2%-15%. Axillary brachial plexus, interscalene, femoral, and sciatic carried a higher risk than others (7).

Additionally, the combination of 10 pounds of traction and the shoulder capsule tightening following capsulorrhaphy could have contributed to this patient developing scapular winging. Upper extremity traction ranging from 10-30 pounds was shown to lead to C5 nerve tension in a magnetic resonance study of five patients by Woodroffe et al (8). The long thoracic nerve has spinal roots of C5, C6, and C7, making it possible to be affected by traction, as described in the above study. It has also been reported that repetitive nerve traction may lead to vascular intimal injury (9). Additionally, we found one case report of a patient with EDS who developed complex scapular winging from spinal accessory and long thoracic neuropathies following a total shoulder arthroplasty (10). This particular patient had an undiagnosed genetic propensity for nerve palsies from pressure and stretch secondary to hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies (HNPP). It was discovered that the patient’s physical therapist had not been stabilizing the scapula while forcefully stretching the upper extremity, likely producing more scapulothoracic motion than glenohumeral motion, leading to stretch injuries to the spinal accessory and long thoracic nerves (10).

Management of scapular winging remains challenging, with conservative measures such as physical therapy often being the first line of treatment (11). The prognosis for patients with medial scapular winging varies, with many experiencing persistent symptoms despite treatment. Regular follow-up and multidisciplinary care are essential to address the multifaceted needs of these patients. In this case, the absence of acute nerve denervation on follow-up nerve conduction studies suggests some degree of nerve recovery. Surgery could be considered for patients with persistent pain, functional impairment, or cosmetic deformity not improved with physical therapy or activity modification. Irreversible nerve injury would also be an indication to consider surgery (12, 13, 14). Surgical options may include long thoracic nerve decompression/neurolysis, tendon transfers such as the Eden-Lange procedure for spinal accessory nerve palsy, or scapulothoracic fusion (12, 13, 14, 15). This patient has completed a full year of a physical therapy program targeting scapular biomechanics and serratus anterior strengthening with improvement, and the plan is for her to continue for at least one more year to maximize her recovery prior to any sort of surgical consideration. This case highlights the importance of considering how hypermobility disorders may affect outcomes after surgery and how peripheral nerve blocks and traction can potentially lead to nerve injuries.

References:

- Lee S, Savin DD, Shah NR, Bronsnick D, Goldberg B. Scapular winging: Evaluation and treatment: AAOS exhibit selection. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2015;97(20):1708-1716. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.O.00727

- Gooding BWT, Geoghegan JM, Wallace WA, Manning PA. Scapular winging. Shoulder Elbow 2013;6:4-11. doi:10.1111/sae.12033

- Srikumaran U, Wells JH, Freehill MT, Tan EW, Higgins LD, Warner JJP. Scapular winging: A great masquerader of shoulder disorders. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014;96-A:1-13. doi:10.2106/JBJS.M.01031

- Galano GJ, Bigliani LU, Ahmad CS, Levine WN. Surgical treatment of winged scapula. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(3):652-660. doi:10.1007/s11999-007-0086-2

- Meininger AK, Figuerres BF, Goldberg BA. Scapular winging: an update. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(8):453-462. doi:10.5435/00124635-201108000-00001

- Vastamäki M, Kauppila LI. Etiologic factors in isolated paralysis of the serratus anterior muscle: A report of 197 cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1993;2(5):240-243. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(09)80082-7.

- Sondekoppam RV, Tsui BC. Factors Associated With Risk of Neurologic Complications After Peripheral Nerve Blocks: A Systematic Review. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(2):645-660. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000001804

- Woodroffe RW, Helland LC, Bryant A, et al. Intraoperative Shoulder Traction as Cause of C5 Palsy: Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. World Neurosurg. 2020;136:e393-e397. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2020.01.024

- Kauppila LI. The long thoracic nerve: Possible mechanisms of injury based on autopsy study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1993;2(5):244-248. doi:10.1016/S1058-2746(09)80083-9

- Skedros JG, Phippen CM, Langston TD, Mears CS, Trujillo AL, Miska RM. Complex Scapular Winging following Total Shoulder Arthroplasty in a Patient with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. Case Rep Orthop. 2015;2015:680252. doi:10.1155/2015/680252

- Kuhn JE, Plancher KD, Hawkins RJ. Scapular Winging. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1995;3(6):319-325. doi:10.5435/00124635-199511000-00002

- Roulet S, Bernier D, Le Nail LR, et al. Neurolysis of the distal segment of the long thoracic nerve for the treatment of scapular winging due to serratus anterior palsy: a continuous series of 73 cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2022;31(10):2140-2146. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2022.02.039

- Maire N, Abane L, Kempf JF, Clavert P; French Society for Shoulder and Elbow SOFEC. Long thoracic nerve release for scapular winging: clinical study of a continuous series of eight patients. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2013;99(6 Suppl):S329-S335. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2013.07.010

- Nath RK, Lyons AB, Bietz G. Microneurolysis and decompression of long thoracic nerve injury are effective in reversing scapular winging: long-term results in 50 cases. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:25. Published 2007 Mar 7. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-8-25

- Sharareh B, Hsu JE, Matsen FA 3rd, Warme WJ. Which Components of the Simple Shoulder Test Show Improvement After Scapulothoracic Fusion for Recalcitrant Scapular Winging? Clinical Results at a Minimum of 5 Years of Follow-up. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2023;481(12):2392-2402. doi:10.1097/CORR.0000000000002673