Ibraheem Qureshi, BS, OMS-III1; Matthew Bernhard, BS, OMS-III1; Aidan Buzard, BS, OMS-II1; Matthew Heffelfinger, DO2; Elizabeth Morrison, MD2

1New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine, 101 Northern Blvd, Glen Head, NY 11545

2Nassau University Medical Center, 2201 Hempstead Tpke, East Meadow, NY 11554

DOI: 10.70709/k4twh2msnb

Abstract

Background

Orthopedic surgery remains male-dominated in research publications. This trend is documented in American journals but has not been compared with foreign journals. This study aimed to analyze the rates of female first authors, senior authors, and overall female authors in top orthopedic journals from the United States, United Kingdom (UK), Germany, and East Asia between 2019 and 2023.

Methods

A retrospective bibliometric review of articles published from 2019 to 2023 in orthopedic journals was conducted using the application Genderize. We determined the genders of first and last authors for each article. ANOVA and chi squared tests were used to assess continuous and categorical variables. Posthoc tests made specific comparisons between groups, and multivariate regression identified factors influencing female authorship.

Results

The United Kingdom had the highest rates of female authors(p<0.001). It also had the highest average and percentage of female authors per manuscript (p<0.001). The UK (OR:2.02;95%CI[1.80,2.27];p<0.001) and East Asia (OR:1.33;95%CI[1.10,1.60] p<0.001) had significantly higher odds of female first authors compared to the US. Germany had lower odds of female first and last authors compared to the US (OR 0.65;95%CI[0.50,0.82];p<0.001). All regions showed increased odds of female first authorship when paired with a female senior author(p<0.001).

Conclusions

The UK excels in promoting female authorship with the highest rates of female authors. This indicates greater inclusion of women. Other countries could reduce gender disparity by studying the UK’s culture and initiatives. All regions experience increased female first authorship under female senior leadership, highlighting the impact of women’s leadership role.

Key Words: Female, authorship, journal, publications, research

Level of Evidence: Level III Retrospective Comparative Study

Introduction

Despite women comprising 51% of American medical students, they remain significantly underrepresented in orthopedic surgery, with only 18.3% of orthopedic residents being female as of 20221,2. Historical analyses reveal similar disparities in research, with women accounting for just 1.7% of senior authors and 4.4% of first authors in orthopedic journals between 1987 and 20173. Research productivity is essential for career advancement in orthopedics, influencing residency placement, promotions, and leadership opportunities4–6. Orthopedic residency program leaders publish an average of 60.7 papers7. Following the USMLE Step 1 shift to pass/fail in 2022, publications have become a key factor distinguishing applicants, with matched orthopedic residents authoring an average of 8.2 scholarly works8. However, the underrepresentation of women in research risks further entrenching gender disparities in this male-dominated field.

While research disparities in other countries have not been comprehensively studied, existing evidence highlights pronounced gender imbalances in orthopedics globally. For example, less than 2.1% of women in Japan who applied to participate in spine surgery conferences over the past decade were accepted as speakers or program editors9. In a study examining 34 international journals across spine, neurosurgery, and orthopedics, women accounted for only 8.84% of editorial board members, with the lowest representation in spine journals (5.53%) and slightly higher rates in neurosurgery (8.58%) and orthopedic journals (10.77%)10 Furthermore, only 5.4% of editors-in-chief were women, underscoring the lack of female leadership in academic publishing globally10. This disparity in leadership may contribute to the lower rates of female authorship, particularly in countries with fewer women in senior roles, as leadership representation often correlates with broader inclusivity11,12. Understanding global rates of female authorship can provide valuable insights into the state of orthopedics in different regions.

The purpose of this study was to analyze female authorship in top orthopedic journals over five years from 2019 to 2023 and compare how far behind or ahead American journals are from gender equality compared to other regions. We aimed to compare female first author rates, senior author rates, and overall female author counts in 12 journals from the United States (US), United Kingdom (UK), Germany, and East Asia. We hypothesized the US would have the best female authorship rates compared to other regions.

Methods

A retrospective bibliometric review was conducted to analyze articles published from 2019 to 2023 in several journals from the US, UK, Germany, and East Asia. The journals included were the American Journal of Sports Medicine (US), Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery (US), Journal of Arthroplasty (US), British Journal of Sports Medicine (UK), The Bone and Joint Journal (UK), Knee Surgery and Related Research (UK), Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy (Germany), Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery (Germany), Journal of Knee Surgery (Germany), Asian Spine Journal (East Asia; South Korea), Journal of Spine Surgery (East Asia; China), and Journal of Orthopaedic Translation (East Asia; Singapore).

These journals were selected on their SCImago journal rank (SJR), clinical orthopedic content, and completeness in data. The SJR score is determined by the average number of weighted citations received in a year by articles published in the journal over the previous three years13,14. Unlike the Impact Factor (IF), which considers citations over a two-year period, the SJR also accounts for the prestige of the citing journal, making it a suitable metric for our analysis13,14. The top three journals were then selected for each country. The East Asia region was created due to the lack of multiple highly rated journals in an individual country. Therefore, the top three overall journals from the Eastern Asian region were selected.

Data was extracted from PubMed and compiled into a data frame, including the year, title, country, and full list of authors. Articles without authors or with incomplete first names were excluded. The dataset was cleaned and analyzed using R (version 4.1.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), and a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Gender identification was performed using Genderize.io (Roskilde, Denmark), a web-based tool that predicts gender based on an extensive repository of over 250,000 names from 242 countries. Authors were categorized as male, female, or undetermined. Names were classified as female if the probability returned by the tool was greater than 70%, a threshold aligned with studies using more liberal criteria4,5,15–17. Articles with undetermined names were excluded.

The number and percentage of female first and last authors were calculated for each journal and each year. Chi-squared tests were used to compare categorical variables, while ANOVA and t-tests were employed to compare author rates between journals and years. Post hoc Fisher’s and Tukey tests were conducted for pair-wise comparisons to identify specific group differences if the overall ANOVA result was statistically significant. The Bonferroni method was used to adjust p-values for multiple comparisons. These statistical methods provided a comprehensive understanding of the comparisons between different countries, with the US serving as primary reference when possible. Finally, multivariate regressions were used to identify factors influencing female authorship.

Results

Authorship Demographics

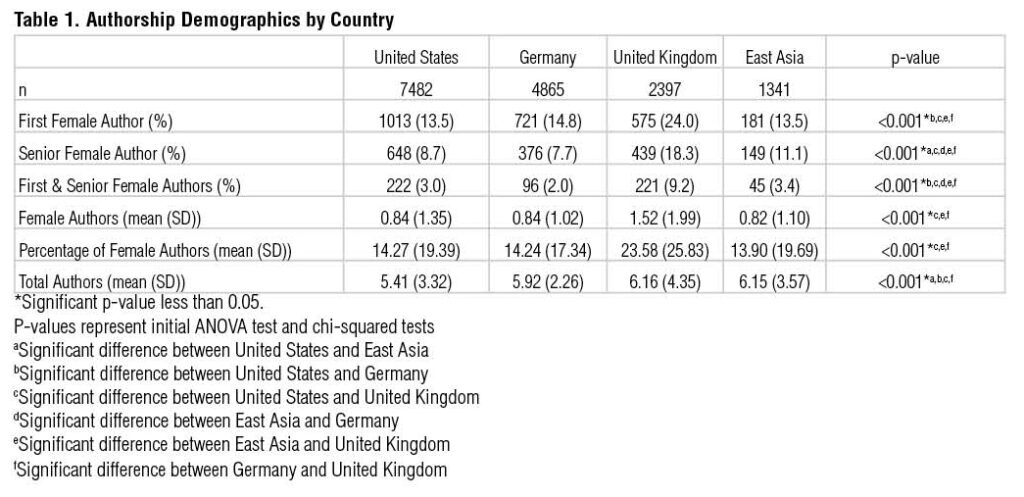

A total of 19,181 articles were returned by PubMed search, of which 16,085 articles met the inclusion criteria in this study. The UK had a significantly higher percentage of first female authors (24%) compared to the US, Germany, and East Asia (Table 1). The US and East Asia had the lowest rates of 13.5% each. The UK had a significantly higher percentage of senior female authors (18.3%, p<0.001) than the other 3 regions. The US and Germany, had the lowest rates of 8.7% and 7.7%, respectively. The UK had a significantly higher percentage of combined first and senior female authors (9.2%, p<0.001). East Asia and the US (3.4% and 3.0%) had a significantly higher percentage of combined first and senior female authors compared to Germany (2.0%, p<0.001). The UK also had the highest average female authors and percentage of female authors per manuscript (1.52 and 23.58%, p<0.001).

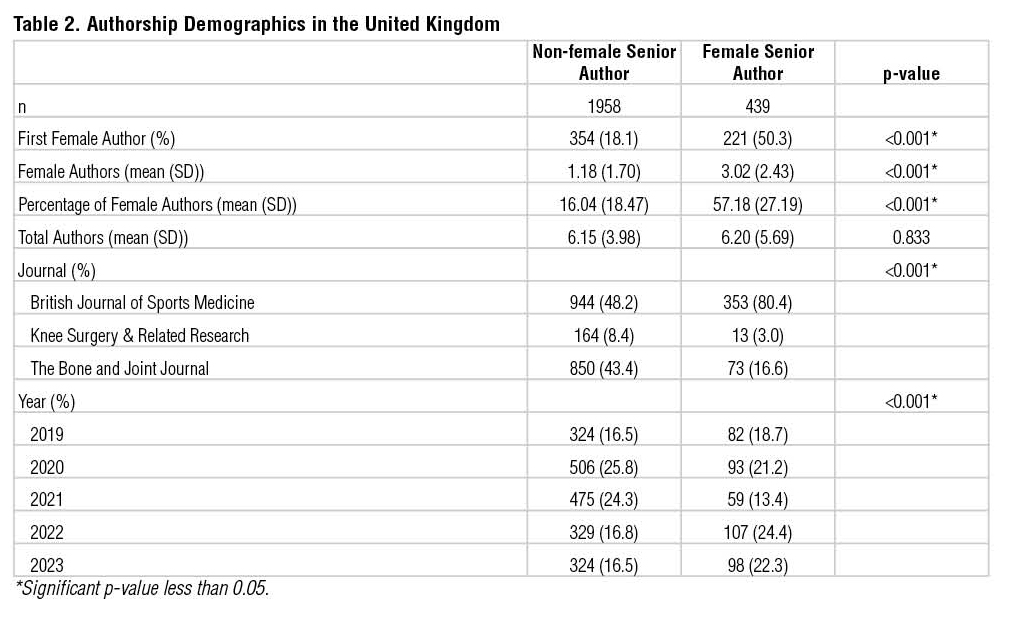

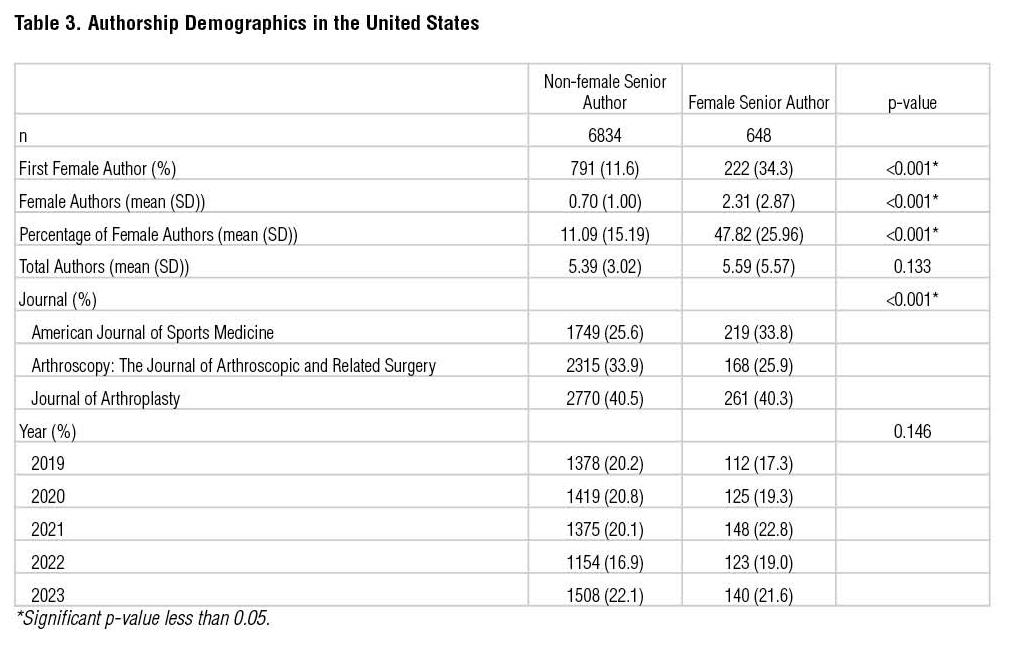

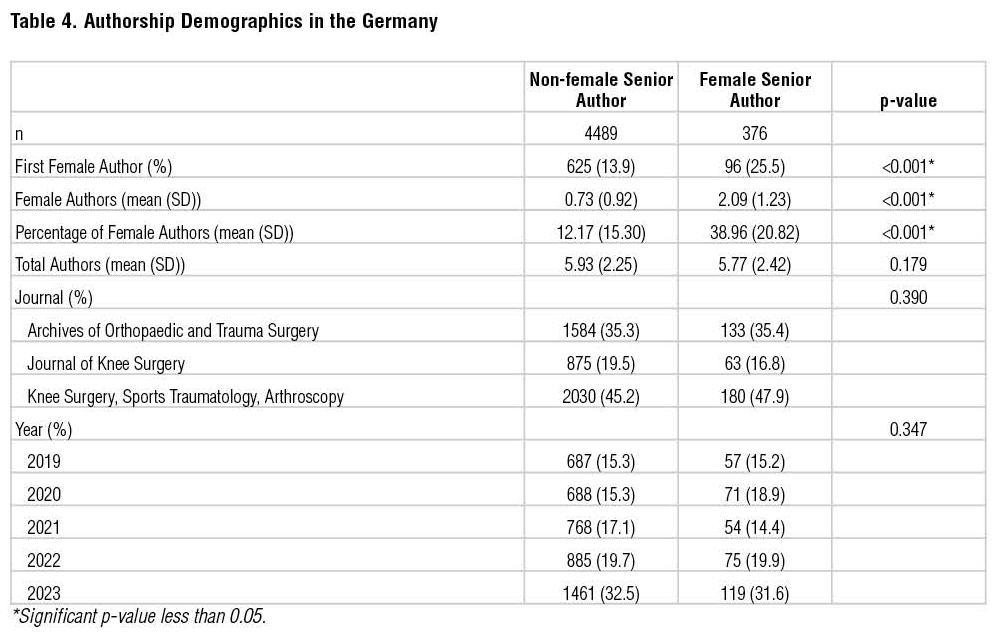

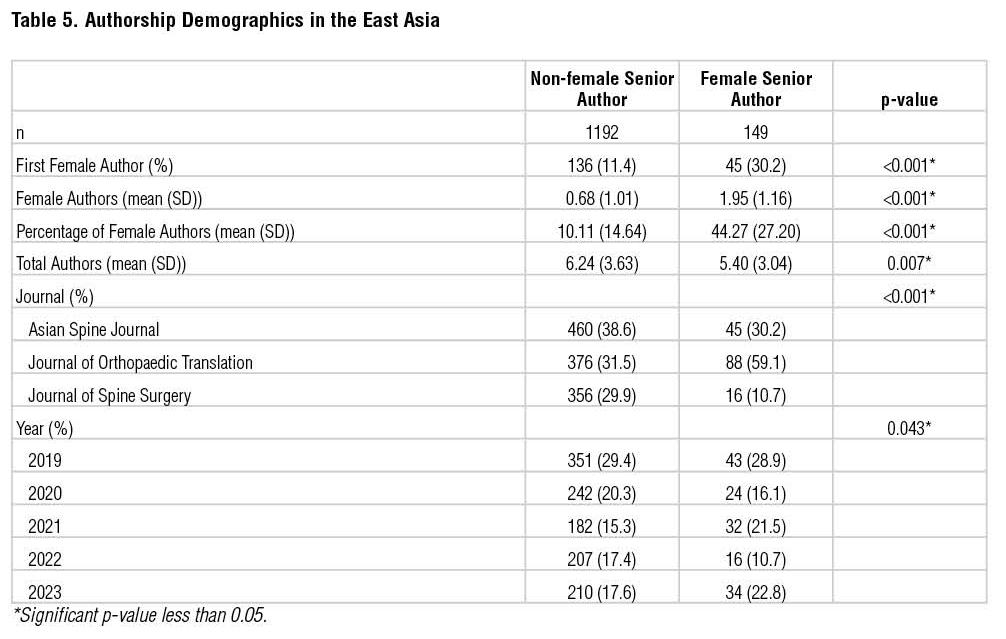

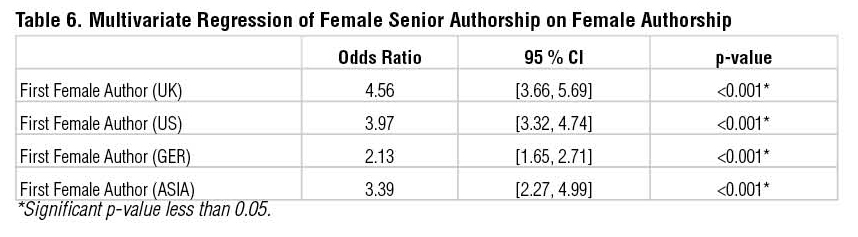

Impact of Female Leadership

Female senior authorship in all four regions showed significantly higher percentages of female first authors (p<0.001), total female authors (p<0.001), and percentage of female authors per manuscript (p<0.001) (Table 2, 3, 4, 5). Female senior authorship in the UK (OR: 4.56; 95% CI [3.66, 5.69]; p<0.001), the US (OR: 3.97; 95% CI [3.32, 4.74]; p<0.001), Germany (OR: 2.13; 95% CI [1.65, 2.71]; p<0.001), and East Asia (OR: 3.39; 95% CI [2.27, 4.99]; p<0.001) showed significantly greater odds for first female authorship (Table 6).

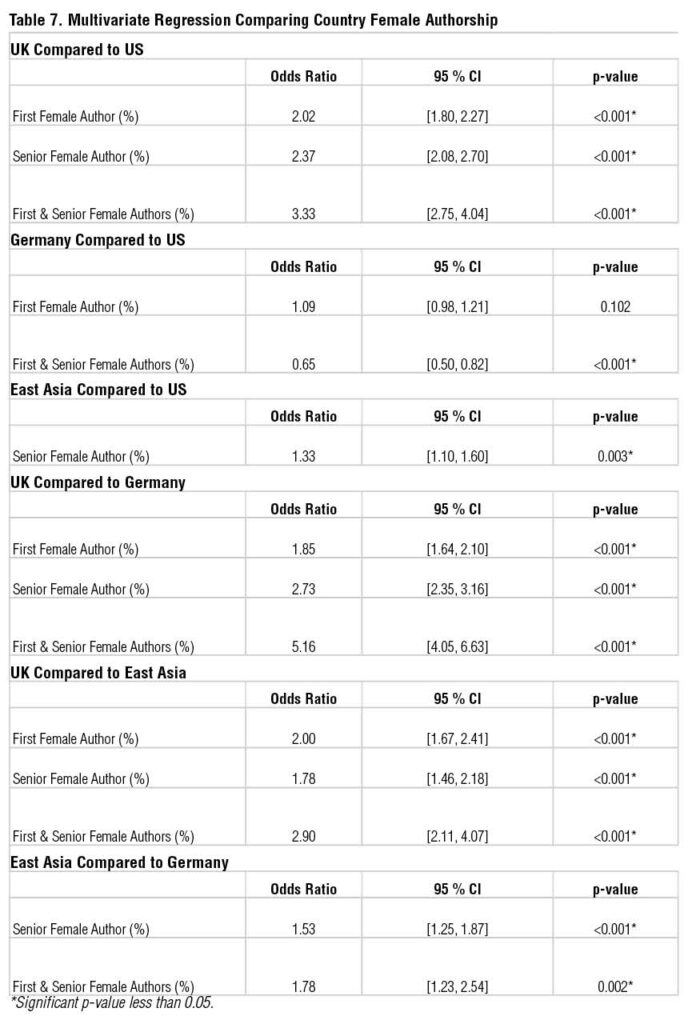

Comparison of Female Authorship Odds by Country

The UK had significantly higher odds of first female authorship compared to the US (OR: 2.02; 95% CI [1.80, 2.27]; p<0.001), Germany (OR: 1.85; 95% CI [1.64, 2.10]; p<0.001), and East Asia (OR: 2.00; 95% CI [1.67, 2.41]; p<0.001) (Table 7). Most importantly, the UK had significantly higher odds of senior female authorship compared to the US (OR: 2.37; 95% CI [2.08, 2.70]; p<0.001) and East Asia had significantly higher odds of senior female authorship than the US (OR: 1.33; 95% CI [1.10, 1.60]; p = 0.003). Furthermore, the UK also had significantly higher odds of combined first and senior female authorship compared to the US (OR: 3.33; 95% CI [2.75, 4.04]; p<0.001). Lastly, Germany showed significantly decreased odds of combined first and senior female authorship compared to the US (OR: 0.65; 95% CI [0.50, 0.82]; p<0.001).

Discussion

The most important finding of this study is that the UK leads in promoting female authorship with the highest rates of female first, last, and combined authorship compared to the US. The UK had 24.0% of articles with first female authors, 18.3% of articles with first senior authors, 9.2% of articles with first and senior female authors, average female author per article at 1.52, average percentage of female authors per article at 23.58%. The US in comparison 13.5% of articles with first female authors, 8.7% of articles with first senior authors, 3.0% of articles with first and senior female authors, average female author per article at 0.84, average percentage of female authors per article at 14.27%. The UK uniformly leads across the board in female rates, while the US is the lowest or tied for the lowest in first female authorship rates, average female authors per article, and average percentage of female authors per article.

Our findings were similar if not better than those found in the current literature. In Germany, women accounted for only 6.1% of orthopedic articles in a German university department18. In the official journal of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association, only 6.5% of first authors were female, and 3.5% senior authors were female19. We found higher rates of female first, senior authorship, and overall involvement in East Asia and Germany. This may be due to the wider scope of our study compared to the ones in Germany and Japan which only looked at a select journal and university. These results show a broader context of the situation in the respective regions.

The gender disparity in orthopedic surgery remains a significant challenge, with female representation notably lower across various professional levels in both the United Kingdom and the US. However, the UK still has markedly better rates than the US. In the UK, 21 percent of orthopedic trainees are women, compared to 18.3 percent in the US, but this representation dwindles at the consultant level, with only 7.3 percent female consultants in the UK and 6 percent in the US1,20–22. These figures reflect broader trends in professional visibility as well: over the past 15 years, only 10.2 percent of speakers at British Orthopaedic Association (BOA) meetings were women, and this figure drops to 6.8 percent for the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS)23,24. Membership statistics reinforce these differences, with women making up 11 percent of BOA membership compared to just 6.5 percent in the AAOS25,26.

Recognizing these challenges, the NHS has implemented initiatives like the Supported Return to Training program, which offers mentorship and coaching to female trainees as they navigate the demands of balancing career and family life20. Additionally, the Royal College of Surgeons, in collaboration with the NHS, created the Women in Surgery network to address the unique needs of female surgeons27. Despite these efforts, projections suggest that gender parity in orthopedic surgery may still be decades away—around 50 years in the UK compared to an estimated 200 years in the US28,29. These stark timelines underscore the need for sustained and proactive measures to close the gender gap in orthopedic surgery. Other countries including the US can learn from British initiatives which are nationally backed and integrated to help women succeed in medicine, especially in demanding specialties.

This study has several limitations that should be considered. First, it used a 70% probability cutoff for gender identification, a more lenient threshold than the 90% cutoff used in some other studies, which could influence accuracy 4,5,15–17. Additionally, the study did not address potential xenophobic biases in publication outcomes, though prior research suggests that non-white names may correlate with lower NIH funding30. While Genderize.io is a robust database, it lacks coverage for every possible name, which may have affected some gender identifications. The study’s scope is limited by its focus on 12 orthopedic journals over a five-year period, which may not fully capture trends across the field. Furthermore, the current proportion of women actively working on unpublished research projects remains unknown. Lastly, although these journals accept submissions from international authors, they largely represent the research priorities, funding structures, and gender dynamics of the regions they are based in due to their editorial boards, primary readership, and publication practices. These contextual factors should be kept in mind when interpreting the findings.

Conclusion

The UK is the most successful in promoting female authorship within academic journals. With the highest rates of female first, last, and combined authorship, women in the UK are more included compared to their colleagues in the USs, Germany, and East Asia. Other countries can learn from studying the culture and initiatives of the UK to decrease the gender disparity in their own countries. Notably, all regions experience significant increases in female first authors under female senior leadership, highlighting the universal impact of prioritizing women’s leadership roles.

References

- The Association of American Medical Colleges. Report on Residents: 2021-22 Active Residents. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/students-residents/interactive-data/report-residents/2022/table-b3-number-active-residents-type-medical-school-gme-specialty-and-gender.

- Van Heest A. Gender Diversity in Orthopedic Surgery: We All Know It’s Lacking, but Why? Iowa Orthop J. 2020;40(1):1-4.

- Brown MA, Erdman MK, Munger AM, Miller AN. Despite Growing Number of Women Surgeons, Authorship Gender Disparity in Orthopaedic Literature Persists Over 30 Years. Clin Orthop. 2020;478(7):1542-1552. doi:10.1097/CORR.0000000000000849

- Zhuge Y, Kaufman J, Simeone DM, Chen H, Velazquez OC. Is There Still a Glass Ceiling for Women in Academic Surgery? Ann Surg. 2011;253(4):637-643. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182111120

- Hart KL, Boitano LT, Tanious A, et al. Trends in Female Authorship in High Impact Surgical Journals Between 2008 and 2018. Ann Surg. 2022;275(1):e115-e123. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000004057

- Ngaage LM, Ngadimin C, Harris C, et al. The Glass Ceiling in Plastic Surgery: A Propensity-Matched Analysis of the Gender Gap in Career Advancement. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;146(3):690-697. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000007089

- Elkadi SH, Donaldson S, Krisanda E, Kessler MW. Trends in Medical Training and Leadership at Academic Orthopedic Programs. Cureus. Published online September 13, 2022. doi:10.7759/cureus.29100

- Toci GR, Elsner JA, Bigelow BF, Bryant BR, LaPorte DM. Medical Student Research Productivity: Which Variables are Associated with Matching to a Highly Ranked Orthopaedic Residency Program? J Surg Educ. 2021;78(2):512-518. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.08.024

- Morimoto T, Kobayashi T, Yamauchi K, et al. Gender Diversity of the Japanese Society for Spine Surgery and Related Research Annual Meetings from 2013 to 2022. Spine Surg Relat Res. 2024;8(1):91-96. doi:10.22603/ssrr.2023-0186

- Ramos MB, Criscuoli de Farias FA, Einsfeld Britz JP, et al. Representation of Women on Editorial Boards of Medline-Indexed Spine, Neurosurgery, and Orthopedic Journals. Int J Spine Surg. 2022;16(2):404-411. doi:10.14444/8223

- Jackson VA, Palepu A, Szalacha L, Caswell C, Carr PL, Inui T. “Having the Right Chemistry”: A Qualitative Study of Mentoring in Academic Medicine. Acad Med. 2003;78(3):328-334. doi:10.1097/00001888-200303000-00020

- Keane AM, Larson EL, Santosa KB, et al. Women in Leadership and Their Influence on the Gender Diversity of Academic Plastic Surgery Programs. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;147(3):516-526. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000007681

- Jones T, Huggett S, Kamalski J. Finding a way through the scientific literature: indexes and measures. World Neurosurg. 2011;76(1-2):36-38. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2011.01.015

- Roldan-Valadez E, Salazar-Ruiz SY, Ibarra-Contreras R, Rios C. Current concepts on bibliometrics: a brief review about impact factor, Eigenfactor score, CiteScore, SCImago Journal Rank, Source-Normalised Impact per Paper, H-index, and alternative metrics. Ir J Med Sci. 2019;188(3):939-951. doi:10.1007/s11845-018-1936-5

- Bernardi K, Lyons NB, Huang L, et al. Gender Disparity Among Surgical Peer-Reviewed Literature. J Surg Res. 2020;248:117-122. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2019.11.007

- Bernardi K, Lyons NB, Huang L, et al. Gender Disparity in Authorship of Peer-Reviewed Medical Publications. Am J Med Sci. 2020;360(5):511-516. doi:10.1016/j.amjms.2019.11.005

- Lerchenmüller C, Lerchenmueller MJ, Sorenson O. Long-Term Analysis of Sex Differences in Prestigious Authorships in Cardiovascular Research Supported by the National Institutes of Health. Circulation. 2018;137(8):880-882. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032325

- Preut J, Frosch KH, Debus ES, Grundmann RT. Bibliometrische Analyse von Forschungsgebieten, Publikationshierarchie und Autorengeschlecht der deutschen universitären Unfallchirurgie und Orthopädie. Z Für Orthop Unfallchirurgie. 2023;161(05):516-525. doi:10.1055/a-1735-4110

- Saka N, Chiang CM, Ogawa T, et al. Trend of female first authorship in Journal of Orthopaedic Science, the official journal of the Japanese orthopaedic association from 2001 to 2021: An observational study. J Orthop Sci. Published online March 2023:S0949265823000775. doi:10.1016/j.jos.2023.03.007

- Ahmed M, Hamilton LC. Current challenges for women in orthopaedics. Bone Jt Open. 2021;2(10):893-899. doi:10.1302/2633-1462.210.BJO-2021-0089.R1

- Malik-Tabassum K, Lamb J, Seewoonarain S, et al. Women in trauma and orthopaedics: are we losing them at the first hurdle? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2023;105(7):653-663. doi:10.1308/rcsann.2022.0112

- Peterman NJ, Macinnis B, Stauffer K, Mann R, Yeo EG, Carpenter K. Gender Representation in Orthopaedic Surgery: A Geospatial Analysis From 2015 to 2022. Cureus. 2022;14(7):e27305. doi:10.7759/cureus.27305

- Krahelski O, Gallivan S, Hing C. How well are women represented at orthopaedic conferences? Bull R Coll Surg Engl. 2020;102(8):382-386. doi:10.1308/rcsbull.2020.206

- Nwosu C, Wittstein JR, Erickson MM, et al. Representation of Female Speakers at the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Annual Meetings Over Time. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2023;31(6):283-291. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-D-22-00615

- Hing C, Pattison G, Gregory R, et al. Diversity and inclusion in trauma and orthopaedics in the UK. J Trauma Orthop. 2020;8(1):52-54.

- Ramos T, Daban R, Kale N, et al. Women in Leadership in State and Regional Orthopaedic Societies. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2022;6(4):e21.00317. doi:10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-21-00317

- Hoyle A, Walsh A, Chatterji S, McNeill H, Davis N. Mentorship for female orthopaedic surgeons. Are we behind the curve? Britishh Orthopaedic Association. March 8, 2021. Accessed October 20, 2024. https://www.boa.ac.uk/resource/mentorship-for-female-orthopaedic-surgeons-are-we-behind-the-curve.html

- Acuña AJ, Sato EH, Jella TK, et al. How Long Will It Take to Reach Gender Parity in Orthopaedic Surgery in the United States? An Analysis of the National Provider Identifier Registry. Clin Orthop. 2021;479(6):1179-1189. doi:10.1097/CORR.0000000000001724

- Newman TH, Parry MG, Zakeri R, et al. Gender diversity in UK surgical specialties: a national observational study. BMJ Open. 2022;12(2):e055516. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055516

- Ginther DK, Schaffer WT, Schnell J, et al. Race, Ethnicity, and NIH Research Awards. Science. 2011;333(6045):1015-1019. doi:10.1126/science.1196783