Andreas N. Christy OMS-IV1,2, Jacob Ward OMS-IV1,2, Marlee Franden OMS-IV2,3, Kaila McCabe1,2,Shrey Mehta, MBBS 2,4, Robert L. Joyner, Jr. PhD, RRT, RRT-ACCS, FAARC2

1Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine

2TidalHealth Richard A. Henson Research Institute

3Rowan-Virtua School of Osteopathic Medicine

4M.P. Shah Medical College

Abstract

Introduction

Achilles tendon ruptures (ATR) are increasingly common in the geriatric population. Recent literature reports a 50% decline in operative procedures among individuals aged 30 to 70, despite a rising overall incidence of orthopedic surgeries. Evaluating standardized outcome measures, such as the Achilles Tendon Total Rupture Score (ATRS) and the American Orthopaedic Foot & Ankle Society (AOFAS) score, along with objective “return to baseline” metrics, is essential for guiding treatment decisions between operative and nonoperative management. This systematic review aims to synthesize current evidence on outcomes following both operative and nonoperative treatment modalities in patients aged 65 and older, to aid clinical decision making.

Methods

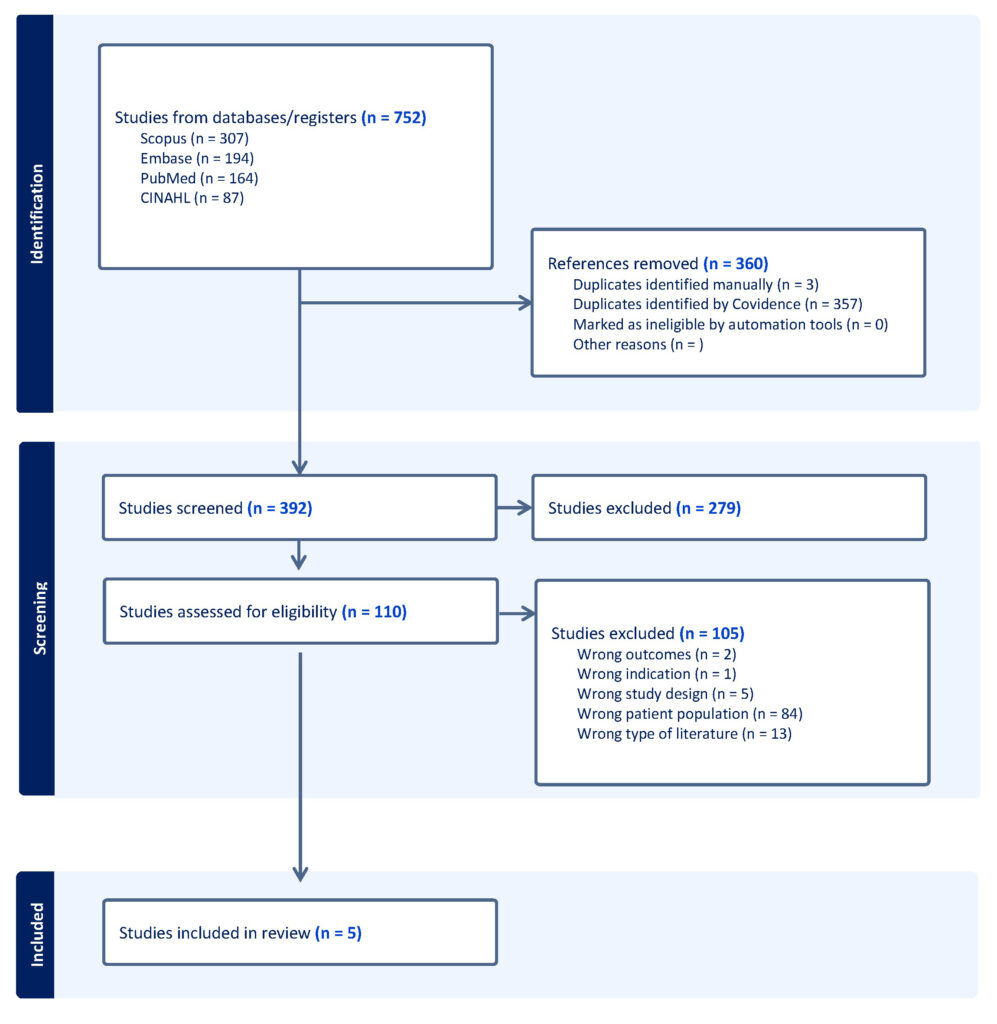

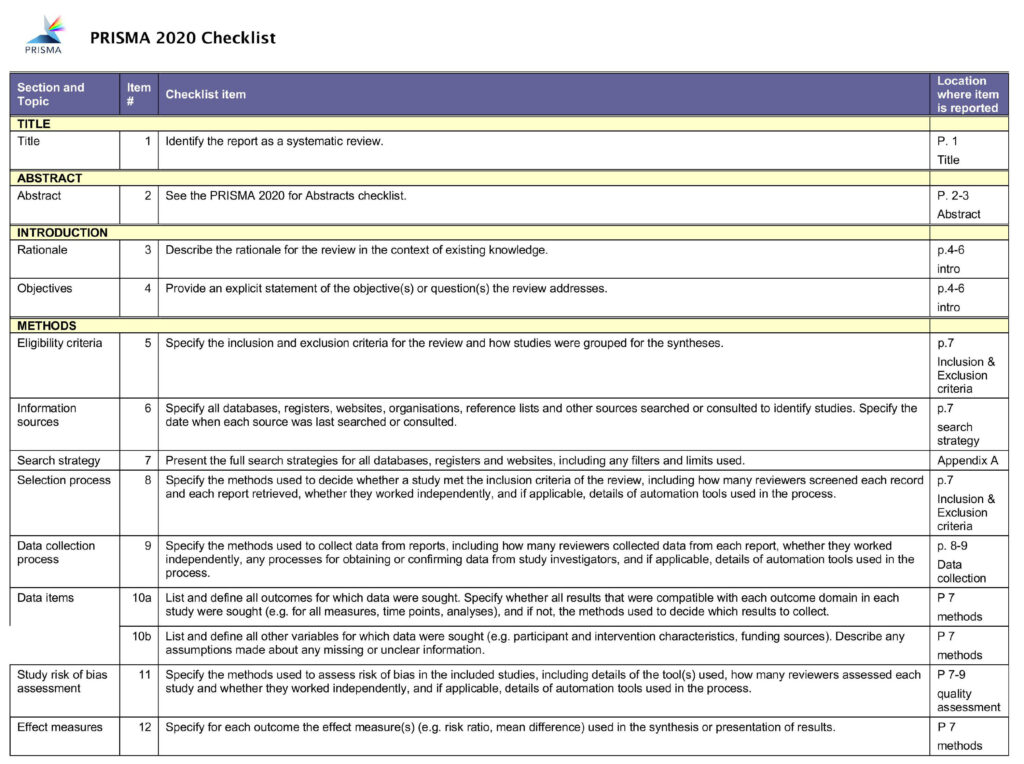

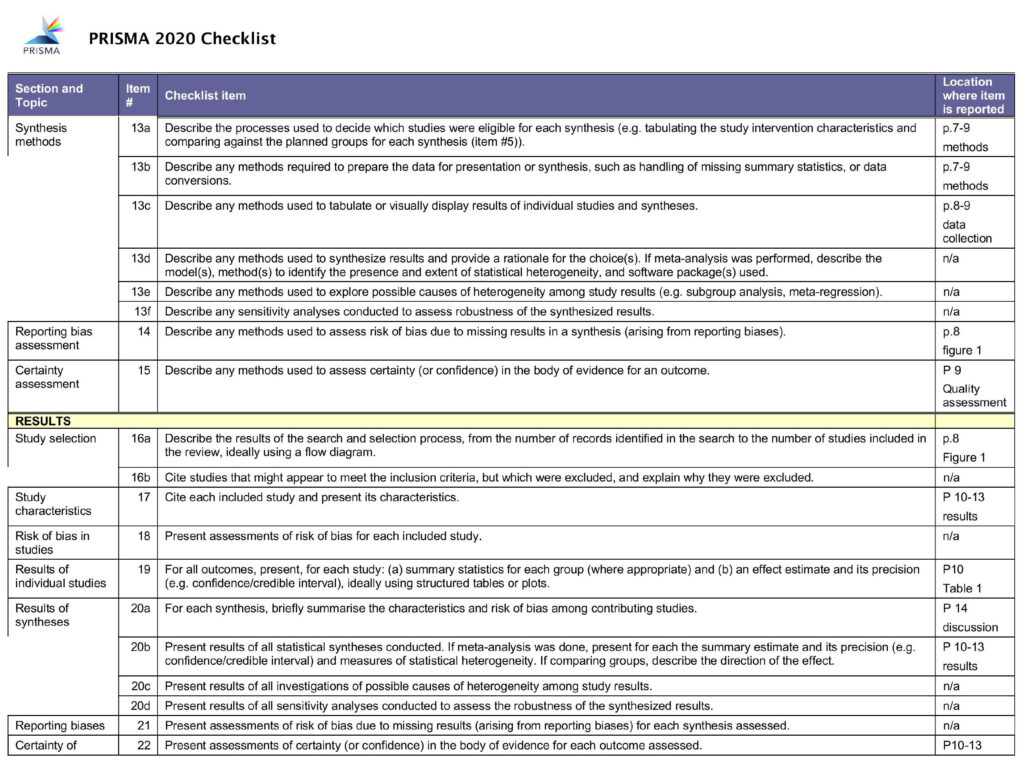

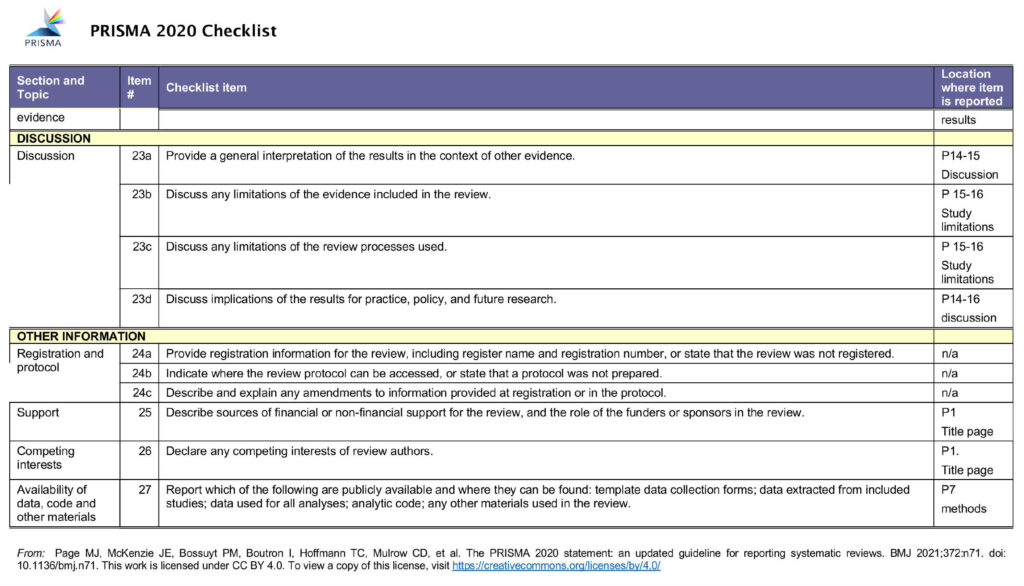

A comprehensive literature search was performed using the following literature databases: PubMed, Embase, SCOPUS, and CINAHL. The search was conducted under the direction of a research librarian. Analogous search strategies were employed across all databases, with filters applied to include only English language studies involving patients aged 65 or older, published between December 2018 and December 2024. The review followed PRISMA 2020 guidelines and was managed using Covidence software (Melbourne, Australia). Of the 752 studies identified, 392 remained after removing duplicate studies, and five met the criteria for data extraction. Two independent reviewers extracted data, requiring a consensus decision for inclusion. Study quality was assessed using the Downs and Black checklist.

Results

Five studies, involving 18 patients, met inclusion criteria. 13 patients underwent operative treatment and five received nonoperative management. Post treatment, 16 patients demonstrated improved ATRS or AOFAS scores; two patients lacked reported outcome scores. 17 patients returned to their pre-rupture functional baseline, while one operative patient reported ongoing restrictions. Overall, the quality of evidence was rated as low to moderate.

Conclusions

In patients aged 65 and older, both operative and nonoperative treatments for Achilles tendon rupture appear to yield comparable outcomes in terms of patient satisfaction and return to baseline function. Given the low to moderate quality of available evidence, further high-quality studies are warranted to strengthen treatment recommendations.

Keywords: Achilles tendon rupture, elderly, operative, nonoperative, outcomes

Introduction

The Achilles tendon is the largest, strongest, and most prone to rupture tendon in the body. Achilles tendon ruptures (ATR) are estimated to occur in 8 in 100,000 individuals annually, with a rising incidence in geriatric patients.1 Factors most associated with rupture in the 65 and over population are age-related changes to tissues, obesity, and chronic inflammatory diseases.1,2 Therefore, selecting the correct treatment plan with the highest likelihood of regaining baseline function in this population is of great importance and is the topic of this systematic review.

The current evidence-based management of ATR aims to secure the tendon in a shortened position and prevent tendon lengthening throughout the recovery period.1 Management can be operative or nonoperative in any population with ATR. Svedman et al. estimated a recent decline in operative treatments in the 30 to 70-year-old population by 50%.3 Nonoperative management of the acute injury phase begins with routine sports injury care, such as rest, ice, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) therapy. Acute care has traditionally been followed by a 6-8 week period of rigid immobilization. However, recent literature reports early functional rehabilitation and strength training as essential in stimulating mechanisms of remodeling and collagen repair to limit atrophy of involved tissue.4,5 Ongoing research lacks consensus on implementing adjunct biologic therapies, such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP), bone marrow aspirate (BMAC), growth factors, scaffolds, and stem cells in nonoperative and operative management.6

Operative management of geriatric patients is indicated but can be more difficult as this population is at a higher risk for complications due to their advanced age and increased prevalence of comorbid conditions.7 Managing chronic ruptures, defined by a time to diagnosis greater than 4-6 weeks after the initial injury, is also more difficult to surgically repair, due to the retraction of tissues creating a gap between the ends of the tendon, preventing primary repair.8 Despite these concerns, the incidence of orthopedic-specific procedures within this population is climbing. Patients over 65 who have undergone a comprehensive pre-surgical screening are viable candidates for open and minimally invasive surgical repair. The recent literature regarding ATR in this population has focused on bone anchor fixation, side-locking loop suture repair, semitendinosus, and flexor hallucis longus tendon transfers.9-12

A return to baseline functioning after an ATR is achievable within the geriatric population. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are routinely used in the pre- and post-operative setting to assess clinical outcomes in managing ATRs. The most used standardized measures, the Achilles Tendon Total Rupture Score (ATRS) and the American Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Society Ankle-Hindfoot Score (AOFAS), exhibit high reliability, validity, and sensitivity in the geriatric population.13 Both scores utilize questionnaires to evaluate subjective outcomes, each with a maximum score of 100, indicating full functionality and no residual symptoms. A minimum score of 0 indicates notable limitations in functionality with severe residual symptoms.13,14 Lower scores indicate poorer functionality. Patient Acceptable Symptom State (PASS) data have been published for the ATRS, and reported thresholds were 49 at 6 months post-injury, 57 at 1 year, and 52 at 2 years. The threshold for Treatment Failure (TF) is 30, 33, and 35.15 The ATRS has been shown to have high reliability, validity, and sensitivity for the geriatric population.13

The purpose of this systematic review was to compile the current evidence on the outcomes following operative and nonoperative management of ATR in the 65 years and older population and to assist in decision making for the treatment of this population.

Methods

Due to the lack of randomized controlled trials in this patient population, this systematic review includes analysis of case reports and retrospective case series, which provided patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) and return to baseline data in both operative and nonoperative treatment of Achilles tendon ruptures during the last 5 years.

Search Strategy:

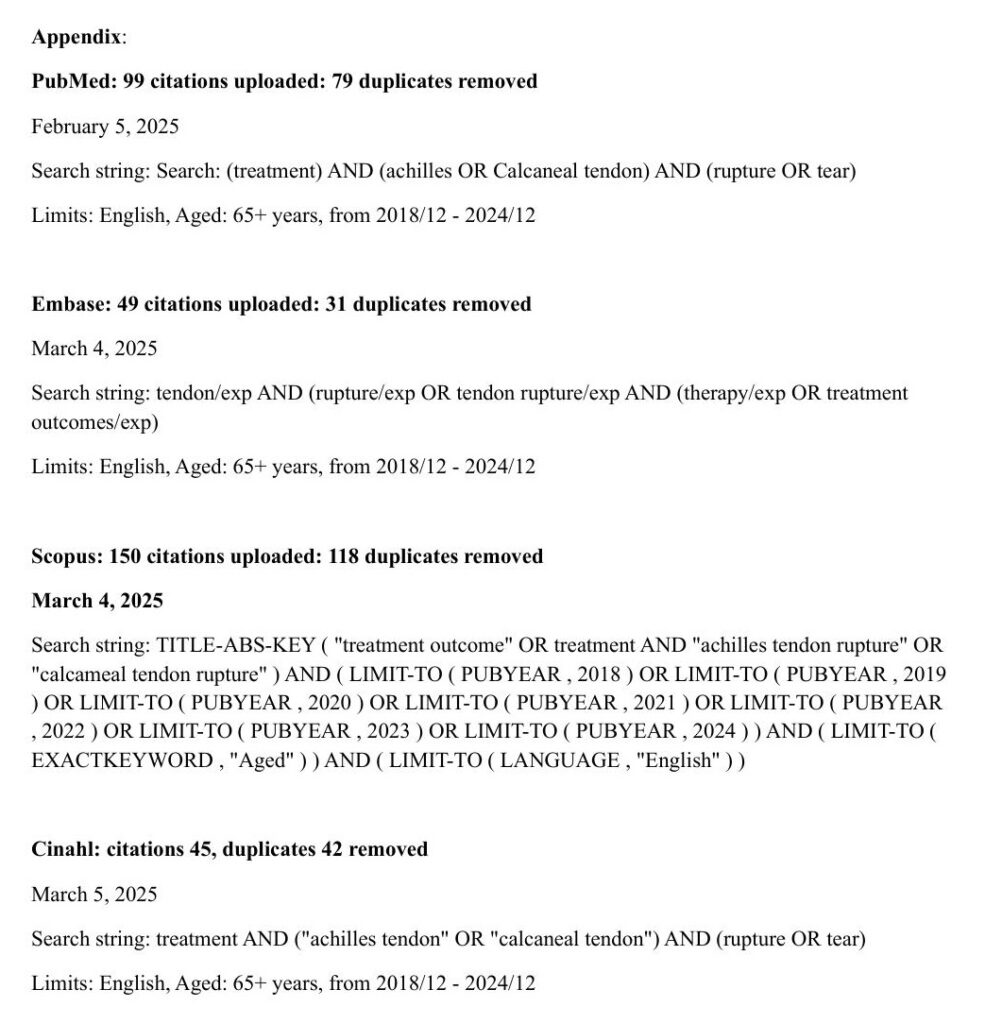

A comprehensive literature search was performed using the following literature databases: PubMed, Embase, SCOPUS, CINAHL. The search was conducted under the direction of a research librarian. Analogous search strings were used in all databases. All complete search strings are available in Appendix A. When possible, limits were placed to include only English language, patient age ≥ 65 years, and from 2018/12 – 2024/12.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria:

Inclusion criteria were the following: age 65+, full thickness unilateral Achilles tendon rupture with attempted management; operative or nonoperative.

Exclusion criteria included any Achilles tendon injury other than full thickness unilateral rupture, patient age <65 years old, history of connective tissue disorder, medication-associated tendinopathy, and incorrect study design (cadaver, abstracts, economics). All reviews and meta-analyses were excluded.

Data Collection:

This systematic review was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines, and using Covidence software (Melbourne, Australia).16 All identified studies went through subsequent rounds of screenings and review for inclusion or exclusion by at least two authors including: Title and Abstract, Full Text review, and Data Extraction. Each study was evaluated by two of six independent reviews in each round of screening. All opinion conflicts were adjudicated in meetings that included all authors and required a unanimous decision for resolution.

Our search identified 752 studies, with 392 studies remaining after duplicate studies were removed. There were 110 studies remaining after the Title and Abstract screening. After full text screening, five studies remained and were included in the data extraction phase. The data was extracted by two independent reviewers (i.e., authors), requiring a consensus decision for inclusion.

Quality Assessment:

The Downs and Black checklist is a 27 item quality assessment tool used in assessing study quality by quantifying characteristics such as quality of reporting, external validity, internal validity, and statistical power.17 Scores range from 0-27; Each of our five included studies were assessed for quality using the Downs and Black checklist.

Results

Subject Data:

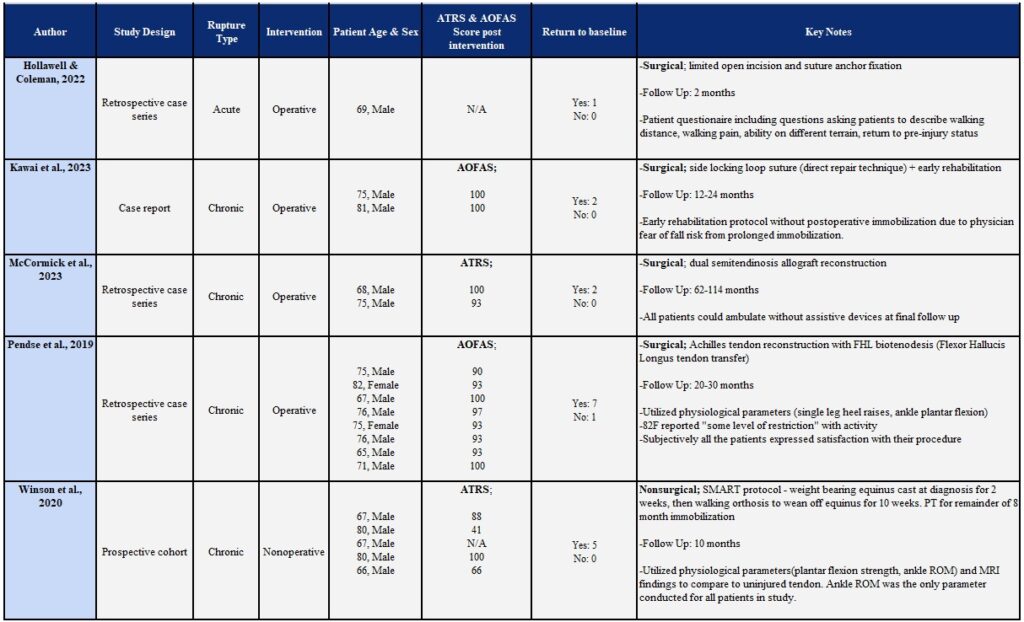

Data on 18 subjects with Achilles tendon rupture was extracted from the studies included. Of these subjects, 16 were male and 2 were female. All subjects were above the age of 65, with ages ranging from 65 to 82 years old. Acute Achilles tendon rupture was diagnosed in 1 participant, with the remaining 17 subjects having a diagnosis of chronic Achilles tendon rupture. Chronic rupture in this paper was regarded as an injury with a time to diagnosis of 4 weeks or greater. Regarding treatment, 13 of these subjects underwent surgical reconstruction and the remaining 5 were managed conservatively with the Swansea Morriston Achilles Rupture Treatment (SMART) protocol.

Patient Reported Outcome Measures

Operative

One study participant underwent surgical repair with limited open incision and suture anchor fixation. No score or outcome measure was reported for this subject. No complications were reported during recovery.9 Two subjects underwent a direct surgical repair technique involving side locking loop sutures. Both subjects reported an AOFAS score of 100 one year later for the first subjects and two years later for the second.10 Eight subjects underwent flexor hallucis longus tendon transfer for Achilles tendon repair. Preoperative AOFAS scores were 49, 56, 58, 58, 56, 56, 58, and 60. AOFAS scores were again collected at 20-30 months after the surgery. Postoperative AOFAS scores were 90, 93, 100, 97, 93, 93, 93, 100, respectively. All subjects reported satisfaction with the procedure and their recovery. Only one of the subjects included in the data set had superficial cellulitis as a complication. It was successfully treated with oral antibiotics.12 The last two subjects in this category were treated with dual semitendinosus allograft reconstruction. ATRS scores were collected at final follow up, which was at 62 months after surgery for one subject and 114 months after surgery for the other. ATRS scores were 93 and 100, respectively. No complications were reported.11

Nonoperative

Nonoperative management data was extracted from participants who took part in the SMART protocol for their injury.18 This protocol involved physiotherapist supervision for 10 weeks in the Achilles clinic. Subjects were treated with 2 weeks of weight bearing equinus cast followed by walking orthosis to gradually transition from the equinus. After orthosis removal, all participants were referred for rehabilitation with physical therapy under strict protocol. Study participants were followed and reviewed for at least eight months after immobilization or until the subject had reached a desired activity level. ATRS were reported at the start of the protocol and at long-term follow-up. The initial ATRS scores reported were 72, 17, 51, 80 and 63. At the long term follow up, the ATRS scores reported were 88, 41, not reported, 100, and 66, respectively. One subject was lost to follow up, which left one score not reported. In this study, no re-ruptures or skin complications were reported.

Return to Baseline

Operative:

Return to baseline was assessed at different intervals for each study involving surgical repair. The study participant who underwent surgical repair with limited open incision and suture anchor fixation returned to pre-injury status at 69 days post-operation.9 For the two subjects that underwent direct repair with side locking loop sutures, both study participants reported no symptoms or dysfunctions in daily activities when their AOFAS was collected.10 At their follow-up 20-30 months post-operation, all but one of the subjects treated with flexor hallucis longus tendon transfer reported the ability to return to pre-injury level of activity.12 The study participant who underwent dual semitendinosus allograft reconstruction had their follow ups at 62 and 114 months after surgery. At these times, both subjects were able to ambulate without assistive devices.11

Nonoperative:

The study evaluating nonoperative management did not comment on the participant’s perceived return to baseline for those treated with the SMART protocol.18 The results did comment, however, on strength testing, ankle range of motion, and MRI examination at follow up. Ankle range of motion was conducted on all study participants in the study, and there was no significant difference between the injured and uninjured ankles in plantarflexion or dorsiflexion. Only 18 out of the 19 study participants underwent MRI imaging and strength testing. When comparing the injured and uninjured side, the mean difference in plantarflexion strength was significant at 21.9%. There was no significant difference found between tendon lengths of the injured and uninjured ankles on MRI. Ankle range of motion testing was used to determine return to baseline since it was the only measured parameter including all participants. Therefore, all five subjects in the reported data returned to baseline. The study reported that all study participants would choose to undergo nonoperative treatment again regardless of scores, if put in a similar circumstance.

Discussion

The findings of this review suggest that elderly patients, aged 65 and older, with Achilles tendon ruptures can achieve positive outcomes through both operative and nonoperative treatment modalities. Among the 18 subjects analyzed, 13 underwent operative management and demonstrated functional recovery. Kawai et al. and Pendse et al. evaluated two and eight subjects respectively, using AOFAS scores, all of which ranged from 90 to 100, indicating full functionality without complications.10 McCormick et al. assessed two subjects using the ATRS, similarly reported high levels of function.11 No score was reported for the single operative subject in the Hollawell & Coleman case series. All but one of the study participants were reported to have returned to baseline function.9 Pendse et al. reported one subject who experienced restrictions in their ability to perform daily activities.12

Nonoperative treatment using the SMART protocol was documented in the remaining study participants by Winson et al., with all five available for initial follow up.18 Four of the study participants showed improved ATRS scores over time, while one study participant did not return to provide a follow-up score. All participants reported satisfaction with their outcome. Notably, each expressed willingness to pursue nonoperative care again if faced with a similar injury. Data regarding the return to baseline was primarily based on physiological parameters and MRI findings compared to the uninjured side. The only data that we can accurately comment on is ankle range of motion, due to it being the only parameter providing data on all study participants. Strength testing was performed, demonstrating comparable strength of the injured side to the uninjured on average. Only 18 of 19 study participants were able to complete this testing, however. Due to the unknown identity of the study participant that did not complete testing, we cannot say with certainty that this individual was not one of those included in our data, therefore, only ankle range of motion was utilized as return to baseline data.

While the studies used different outcome measures and had some variability in methodology, both operative and nonoperative treatments resulted in satisfactory return to function in patients 65 and older.

This review focused strictly on patients within the geriatric population as defined by Medicare in the United States, excluding any studies where data was averaged across broader age groups to reduce confounding. Though promising, these findings are based on limited available data, underscoring the need for further research.

Existing literature highlights the paucity of data on Achilles tendon ruptures in the geriatric population, likely due to concerns surrounding surgical risks. Comorbidities, degenerative tissue changes, and increased complication rates often drive patients toward conservative treatment, or away from treatment entirely.19 Additionally, geriatric patients may choose to forgo treatment due to lower baseline functional demands compared to younger, more active individuals. As the mean age of the global population continues to rise, the incidence of Achilles tendon rupture in older adults will follow suit,20 making this an increasingly relevant clinical issue. There is a pressing need for standardized treatment guidelines specifically directed towards this age group.

Study Limitations

The adherence to PRISMA 2020 guidelines contributed to a structured and replicable review process. By establishing inclusion criteria a priori, this review aimed to minimize selection bias inherent to this type of study. Our study addresses a novel question by focusing on a population that is seemingly rarely considered in large-scale trials regarding this injury type. Through the incorporation of individualized patient data from case studies and case series, meaningful data was able to be collected despite there being limited large scale trials available. This method of data acquisition is not typical for a systematic review, adding a unique element to the data provided. While the use of these studies allowed for meaningful insights in the absence of randomized controlled trials, it also limited the strength of evidence to low and moderate quality. Variability in surgical techniques, outcome measures, injury types, and diagnosis timelines further constrained our ability to perform subgroup analysis or apply findings broadly.

Conclusion

The primary endpoint, patient reported outcome measures, suggests comparable outcomes between operative and nonoperative treatment options in this population. For the secondary endpoint, most study participants returned to their baseline activity level, though recovery timelines varied by treatment type.

From a clinical perspective, our findings support nonoperative treatment for an Achilles tendon rupture as a viable option for elderly patients who are not ideal surgical candidates. While both treatment approaches indicate a return to function, the timeline and road to recovery should be discussed with patients during shared decision-making. Importantly, our findings highlight a noticeable gap in high-quality data for this growing population.

Elderly patients, aged 65 years and older, can achieve high levels of satisfaction and functional return to pre-rupture baseline following both operative and nonoperative management for an Achilles tendon rupture. These results, while limited, suggest that individualized treatment planning can be effective in this population.

Future Research

These findings provide some data, yet it is evident that there is a deficit of high-quality research for this expanding population of elderly patients. To address this gap, large scale, multicenter database reviews are needed to increase the data pool, with a focus on standardized treatment protocols and consistent long term follow-up reporting. Future research should aim to rigorously compare operative and nonoperative outcomes targeting elderly patients with Achilles tendon ruptures.

References

- Ivanova VS, Sieu Tong KP, Neagu C, King CM. Current Concepts in Achilles Tendon Ruptures. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. Jan 2024;41(1):153-168. doi:10.1016/j.cpm.2023.09.001

- Briggs-Price S, Mangwani J, Houchen-Wolloff L, et al. Incidence, demographics, characteristics and management of acute Achilles tendon rupture: An epidemiological study. PLoS One. 2024;19(6):e0304197. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0304197

- Svedman S, Marcano A, Ackermann PW, Fellander-Tsai L, Berg HE. Acute Achilles tendon ruptures between 2002-2021: sustained increased incidence, surgical decline and prolonged delay to surgery-a nationwide study of 53 688 ruptures in Sweden. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2024;10(3):e001960. doi:10.1136/bmjsem-2024-001960

- Park SH, Lee HS, Young KW, Seo SG. Treatment of Acute Achilles Tendon Rupture. Clin Orthop Surg. Mar 2020;12(1):1-8. doi:10.4055/cios.2020.12.1.1

- Morelli V, James E. Achilles tendonopathy and tendon rupture: conservative versus surgical management. Prim Care. Dec 2004;31(4):1039-54, x. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2004.07.009

- Shapiro E, Grande D, Drakos M. Biologics in Achilles tendon healing and repair: a review. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. Mar 2015;8(1):9-17. doi:10.1007/s12178-015-9257-z

- Theodorakis N, Nikolaou M, Hitas C, et al. Comprehensive Peri-Operative Risk Assessment and Management of Geriatric Patients. Diagnostics (Basel). Sep 27 2024;14(19)doi:10.3390/diagnostics14192153

- Maffulli N, Via AG, Oliva F. Chronic Achilles Tendon Rupture. Open Orthop J. 2017;11:660-669. doi:10.2174/1874325001711010660

- Hollawell S CM. Achilles tendon repair with limited incision and anchor fixation: Case series results. Foot & Ankle Surgery Techniques Reports & Cases. 2022;2(2)doi:10.1016/j.fastrc.2022.100175

- Kawai A, Morimoto S, Morio F, Tachibana T, Iseki T. Chronic Achilles tendon rupture in elderly treated with a combination of the side-locking loop suture technique and early rehabilitation protocol: two cases report. J Surg Case Rep. Jun 2023;2023(6):rjad339. doi:10.1093/jscr/rjad339

- McCormick BP, Trent S, Haislup BD, Bolster D, Bubnash K, Miller SD. Dual Semitendinosus Allograft Reconstruction of Chronic Achilles Tendon Ruptures: Operative Technique and Outcomes. Foot Ankle Int. Jan 2023;44(1):48-53. doi:10.1177/10711007221138239

- Pendse A, Kankate R. Reconstruction of chronic achilles tendon ruptures in elderly patients, with vascularized flexor hallucis longus tendon transfer using single incision technique. Acta Orthop Belg. Mar 2019;85(1):137-143.

- Opdam KTM, Zwiers R, Wiegerinck JI, et al. Reliability and validation of the Dutch Achilles tendon Total Rupture Score. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. Mar 2018;26(3):862-868. doi:10.1007/s00167-016-4242-7

- Van Lieshout EM, De Boer AS, Meuffels DE, et al. American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) Ankle-Hindfoot Score: a study protocol for the translation and validation of the Dutch language version. BMJ Open. Feb 27 2017;7(2):e012884. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012884

- Cramer A, Ingelsrud LH, Hansen MS, Holmich P, Barfod KW. Estimation of Patient Acceptable Symptom State (PASS) and Treatment Failure (TF) Threshold Values for the Achilles Tendon Total Rupture Score (ATRS) at 6 Months, 1 Year, and 2 Years After Acute Achilles Tendon Rupture. J Foot Ankle Surg. May-Jun 2022;61(3):503-507. doi:10.1053/j.jfas.2021.09.026

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. Mar 29 2021;372:n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71

- Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. Jun 1998;52(6):377-84. doi:10.1136/jech.52.6.377

- Winson DMG, MacNair R, Hutchinson AM, Owen NJ, Evans R, Williams P. Delayed Achilles tendon rupture presentation: Non-operative management may be the SMART choice. Foot (Edinb). Mar 2021;46:101724. doi:10.1016/j.foot.2020.101724

- Abduljawad SM, Almonla Y, Bin Sahl A, Balvinder R, Pillai A. Factors That Determine the Outcomes of Surgical Versus Conservative Management in Achilles Tendon Ruptures: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Cureus. Nov 2024;16(11):e74338. doi:10.7759/cureus.74338

- Sonohata M, Okamoto T, Uchihashi K, et al. Subcutaneous Achilles tendon rupture in an eighty-year-old female with an absence of risk factors. Orthop Rev (Pavia). Mar 20 2010;2(1):e11. doi:10.4081/or.2010.e11