Trent Davis, BS (Medical Student)1; Justin T Butler, DO (Adult Hip and Knee Reconstruction Fellow)2; Samuel D. Stegelmann, MD (PGY-2 Resident)3; Kevin Brown, BA (Medical Student)4; Amy Singleton, DO (PGY-3 Resident)5; Logan M Druessel, DO (Research Fellow)5; Richard M Miller, DO (Program Director)5

1Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, Athens, OH

2The CORE Institute Specialty Hospital, Phoenix, AZ

3Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Medical City Denton, Denton, TX

4University of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences, Toledo, OH

5 Department of Orthopedics, Mercy Health, St. Vincent Medical Center, Toledo, OH

DOI: http://doi.org/10.70709/vsa7kr

Abstract

Background

Participation in outpatient clinics is an essential component in the curriculum of many orthopedic surgery residency programs, yet surgeons’ perceptions of their usefulness remain relatively unclear.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the perceived value of the orthopedic surgery resident-run clinic (RRC) compared to an attending’s personal clinic (APC), and how these experiences affected one’s readiness for clinical practice.

Methods

A web-based questionnaire (via SurveyMonkey) was distributed in 2022 to practicing and retired orthopedic surgeons via the American Osteopathic Academy of Orthopedics. A total of 118 participants reported on 24 items regarding training background and experiences in RRC and/or APC.

Results

More respondents felt that aspects of APC were helpful to current practice (98.2% vs 91.3%, p = 0.038), and more identified aspects of RRC where they needed more experience (40.44% vs 58.8%, p = 0.018). The three most beneficial aspects of APC and RRC included physical exam skills (91.7% vs 85.0%), making a diagnosis (79.8% vs 81.3%), and patient communication/empathy (70.6% vs 63.8%). The three most reported aspects that respondents needed more experience with were understanding billing, coding, and insurance (28.4% vs 45.0%), formulating a treatment plan (14.7% vs 15.0%), and efficiency per encounter (9.2% vs 20.0%).

Conclusions

Our findings reveal that participation in both RRC and an APC during residency is highly valued by orthopedic surgeons, and helpful for their transition to clinical practice. However, areas for improvement were more commonly identified with RRC, which highlights opportunities for continued development of resident education.

Abbreviations

ACGME, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; APC, attending’s personal clinic; RRC, resident-run clinic; AOAO, American Osteopathic Academy of Orthopedics; APP, advanced practice providers; DO, Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine

Keywords: Orthopedic surgery; Clinic; Resident; Attending; Residency; ACGME

Introduction

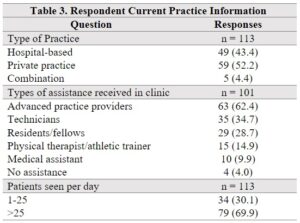

Competency-based education has emerged in the 21st century as a focus in orthopedic surgery residency programs.1 In the United States, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) introduced several initiatives to incorporate competency-based education into the residency accreditation process, defining 6 core competencies essential to resident education (Table 1). These core competencies are broken down into orthopedic-specific sub-competencies to further assess clinical and operative milestones. One crucial aspect influencing the preparedness for orthopedic practice is the ability to independently function in an outpatient clinic.2,3 In a survey distributed by the American College of Surgeons, program directors stated that relative to graduating residents ten years prior, current residents were less prepared in clinical decision-making (51%), and clinical skills (48%).3. Analysis of the benefits and drawbacks of different clinic structures will help orthopedic residency programs supplement deficient competencies.

A large portion of orthopedic surgery residency education is spent in outpatient clinics,4 which enables residents to develop many ACGME competencies and clinical skills. Two common clinic structures used by orthopedic surgery residencies include a resident-run clinic (RRC) or an attending’s personal clinic (APC). The utility of RRC has been well-documented in other surgical subspecialties, such as general surgery,5-7 plastic surgery,8,9 urology,2 and hand surgery.10 Despite studies in other specialties, there is a lack of literature detailing the perceived value of clinic during orthopedic surgery residency training and how this experience affects an orthopedic surgeon’s preparedness for clinical practice. As clinical experiences comprise a significant portion of the curriculum in many residency programs, gaining insight into how clinic influences a resident’s transition to clinical practice and ability to meet ACGME milestones prior to graduation can aid residency programs by identifying subject areas that may need improvement.

In the present study, we sought to characterize practicing orthopedic surgeons’ participation in RRC and/or an APC during residency and its perceived helpfulness in improving clinical skills. We secondarily aimed to compare recalled helpfulness of RRC and APC between practicing physician subgroups (clinic frequency, volume, and assistance type during residency as well as the practicing surgeon’s post-graduate training, current practice setting, and years in practice).

Material and Methods

Setting & Participants

This cross-sectional, questionnaire-based study was conducted with members of the AOAO and all physicians on their mailing list. The survey was distributed via email by a representative of the AOAO. The email included a link to a web-based anonymous self-assessment questionnaire (SurveyMonkey, Momentive, San Mateo, CA). The initial email was sent on August 20, 2022, with a reminder email sent on September 8, 2022. Responses were accessed two months after the reminder email was sent. Responses were included if the respondent was a currently practicing or retired orthopedic surgeon and had at least 1 year of experience as a practicing physician.

Interventions

The survey was developed at a single institution, using feedback from orthopedic surgery residents and program faculty to explore key aspects of clinic that were felt to have applications in an orthopedic surgeon’s practice. The survey consisted of 24 questions, with information collected on demographics, experience with an RRC, experience with an APC, and characteristics of current practice. Survey questions are provided in supplemental attachment.

Outcomes Measured

Demographic data collected included: year of graduation from residency; geographic region and specific program in which they completed their residency; whether they completed a fellowship; the specific fellowship completed; and years in clinical practice. The recalled frequency and number of patients seen in clinic determined patient volume. Participants recalled if the clinic type was helpful or if they required more experience for each orthopedic ACGME core and sub-competencies during his or her residency training. The final questions asked about the setting (i.e., hospital-based vs private), assistance received (i.e., nurse practitioners/physician assistants, residents, etc.), and volume of current clinic days. Furthermore, respondents were asked if they would participate in RRC and/or APC again during residency.

Data Analysis

Individual responses were collected for all respondents. Categorical data was analyzed using chi square tests or Fisher’s exact tests. Subgroup analysis was performed pertaining to clinical experiences, which grouped respondents by fellowship training (fellowship vs no fellowship), practice setting (hospital vs private practice), years in practice (≤15 years vs >15 years), days spent in clinic per week (1 day vs >1 day), and patients seen per clinic day (≤10 vs >10). Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 9.4.1 (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Background Respondent Information

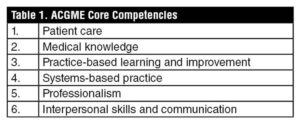

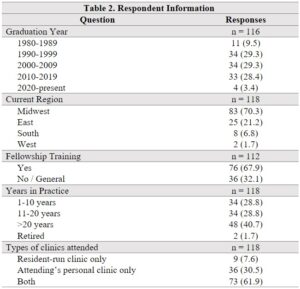

A total of 126 responses were received. Eight were excluded due to incompletion, resulting in 118 responses for analysis. Background information and current practice information are shown in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. Graduation year from orthopedic surgery residency program ranged from 1980 to 2021, with 54.2% of respondents reporting more than 15 years of practice. Most respondents attended programs in the Midwest (70.3%, 83/118), and most completed a fellowship following their residency training (67.9%, 76/112) (Fig. 1). The clinical setting of the respondents’ current practice varied, including 52.2% (59/113) in private practice, 43.4% (49/113) who were hospital-employed, and 4.4% (5/113) whose practice was a combination of hospital-based and private. The most frequent types of assistance received during clinic were from advanced practice providers (APPs, 62.4%, 63/101), technicians (34.7%, 35/101), and residents or fellows (28.7%, 29/101). Additionally, 69.9% (79/113) of respondents reported seeing more than 25 patients per day in their current clinical practice.

Data presented as n (%).

Data presented as n (%). Hospital-based practice includes hospital-based independent practitioners, hospital-based groups, and hospital-based academic faculty. Private practice includes independent practitioners and private group practices. Advanced practice providers (APPs) includes either nurse practitioners and/or physician assistants.

Figure 1. Fellowship training among respondents.

Clinic Participation during Residency

Most respondents participated in both an RRC and an APC during residency (61.9%, 73/118), while 7.6% (9/118) participated in only RRC and 30.5% (36/118) participated in only an APC. Overall, a higher proportion of respondents attended an APC compared to an RRC (92.4%, 109/118, vs 69.5%, 82/118, p < 0.0001). Most spent only 1 day per week in either an APC (53.7%, 58/108) or RRC (77.8%, 63/81), although a higher proportion of respondents spent more than 1 day per week in an APC compared to RRC (46.3%, 50/108, vs 22.2%, 18/81, p = 0.0007). Additionally, a higher proportion saw more than 10 patients per clinic day in an APC compared to an RRC (67.6%, 73/108, vs 39.5%, 32/81, p = 0.0002) (Table 4).

Data presented as n (%).

RRC, resident run clinic; APC, attending’s personal clinic; EMR, electronic medical record.

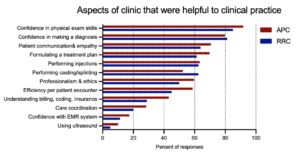

Helpful Aspects of Clinic

Most respondents identified helpful aspects of both types of clinics, although a higher proportion reported helpful aspects of an APC compared to an RRC (98.1%, 107/109, vs 91.3%, 73/80, p = 0.039). The three most common helpful areas were the same for both clinic types, which included confidence in physical exam skills (91.7% APC, 100/109, vs 85.0%, 68/80, RRC), confidence in making a diagnosis (79.8%, 87/108, APC vs 81.3%, 65/80, RRC), and patient communication skills and empathy (70.6%, 77/108, APC vs 63.8%, 51/80, RRC) (Fig. 2). Among the specific areas, a significantly higher proportion of respondents found an APC helpful in understanding billing, coding, and insurance (43.1%, 47/109, vs 28.8%, 23/80, p = 0.049), and efficiency per encounter trended in the same direction (58.7%, 64/109, vs 45.0%, 36/80) p = 0.077) (Table 4).

Figure 2. Respondent answers to specific areas of their clinic experience that were helpful to their current clinical practice.

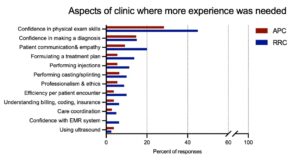

Areas where More Experience was Needed

A higher proportion of respondents identified aspects of RRC where they needed more experience compared to an APC (58.8%, 47/80, vs 40.4%, 44/108, p = 0.018). The three most common areas between both clinic types were again the same, which included understanding billing, coding, and insurance (45.0%, 36/80, RRC vs 28.4%, 31/108, APC), formulating a treatment plan (15.0%, 12/80, RRC vs 14.7%, 16/108, APC), and efficiency per patient (20.0%, 16/80, RRC vs 9.3%, 10/108, APC) (Fig. 3). A significantly higher proportion felt that an RRC did not fulfil their experience regarding understanding billing, coding, and insurance (p = 0.031), and casting and splinting (6.3%, 5/80, RRC vs 0%, 0/109, APC, p = 0.013). Additionally, efficiency per encounter trended in the same direction (20.0%, 16/80, RRC vs 9.3%, 10/108, APC, p = 0.053) (Table 4).

Figure 3. Respondent answers to aspects of their clinic experience that needed more attention.

Subgroup Analysis

A higher proportion of fellowship-trained respondents felt they needed more experience with aspects of an APC (48.6%, 34/70, vs 26.5%, 9/34, p = 0.036). However, no other significant differences among responses were found related to the volume or frequency of clinic during residency, current practice setting, assistance from APPs or residents/fellows, and years in practice (Table 5).

If respondents were to complete residency again, 86.8% (101/116) reported that they would participate in both RRC and APC during their training. Overall, a similar proportion said they would attend an RRC compared to an APC (90.4%, 104.86/116, vs 96.5%, 111.94/116, p = 0.106).

Data presented as n (%). Hospital-based practice includes hospital-based independent practitioners, hospital-based groups, and hospital-based academic faculty. Private practice includes independent practitioners and private group practices. Advanced practice providers (APPs) includes either nurse practitioners and/or physician assistants. RRC, resident run clinic; APC, attending’s personal clinic; APP, advanced practice providers

Discussion

The results of the current study provide important insights into the skills and experience developed through RRCs and APCs. Our findings reveal that participation in either an RRC or an APC during residency is highly valued by orthopedic surgery attendings, and that most found aspects of both clinics to be helpful to their current practice. However, responses on aspects needing more attention address areas of an RRC that programs can focus on to improve the resident experience.

Despite a lack of literature documenting RRCs in orthopedic surgery, other subspecialties have demonstrated that these can be effective learning environments. For instance, literature in plastic surgery has shown that aesthetic clinics have helped residents surpass ACGME caseload requirements, while maintaining complication rates that are equivalent to faculty and national averages.11-15 These clinics have gained popularity in recent years, as the number of institutions providing an aesthetic RRC increased from 33% in 2014 to 47% in 2017.16 Plastic surgery residents have consistently reported that clinic positively contributed to their education.12,17,18 Similarly, Wojcik et al.7 evaluated the experiences in a resident-run minor surgery clinic, finding that it increased general surgery residents’ perceived ability to independently perform procedures. Overall, the success of an RRC in other subspecialties suggests that it could be a valuable tool for enhancing the education of orthopedic surgery residents as well.

Our findings demonstrate similar sentiments towards clinic participation as previous studies, although unlike these studies, our respondent group of practicing orthopedic surgeons provided insight on their preparedness for clinical practice. In total, 91.3% found RRC helpful and 90.4% stated they would participate in RRC if they were to do residency again. At least 60% of respondents found RRC to enhance their physical exam skills, confidence in making a diagnosis, procedural skills (including casting/splinting and injections), patient communication, and their ability to formulate a treatment plan. These findings indicate that RRC provides an opportunity for autonomous, hands-on learning, which allows residents to develop an array of skills that are critical as an attending physician. From the perspective of the ACGME orthopedic surgery milestones, participation in RRC fosters critical development in all six core competencies and several sub-competencies. Additionally, RRC can promote interpersonal team building and comradery by enabling residents to work together in a similar setting.

This study also identifies areas of RRC that may need more attention to maximize a resident’s preparedness for clinical practice, as a significantly higher proportion of respondents felt that there were aspects of RRC that they needed more experience with. Understanding billing, coding, and insurance was the most common area among both clinic types where respondents felt they needed more experience, and it was also the main discrepant area between the two (28.4% for APC vs 45.0% for RRC, p = 0.022). This indicates that more experience in this area is needed regardless of clinic type, but it is especially important in RRC where residents may not receive the same degree of direct mentorship for this practical knowledge. Familiarity with billing, coding, and insurance has previously been identified in literature as a deficient area among orthopedic surgery residents. Varacallo et al.19 found that while senior residents reported higher self-perceived comfort levels, there were no differences between senior and junior residents on baseline examination scores that tested basic documentation, coding principles, and identification of Medicare fraud. Their findings suggest that resident awareness of a deficiency may be lacking later in residency. Furthermore, the authors provided a high-yield 45-minute teaching session, which significantly improved examination scores among all resident levels. Based on the findings of our study, it may be necessary to implement a similar method of targeted, high-yield education to ensure that residents have a sufficient understanding of billing, coding, and insurance for clinical practice, especially for programs that use RRC.

Efficiency per patient encounter also appeared to benefit more from an APC. The respondents trended towards indicating that an APC helped with efficiency per patient encounter more frequently than an RRC, and that they needed more experience with improving their efficiency per patient encounter in an RRC than an APC. However, the results were statistically non-significant. This finding may be related to the higher proportion of respondents that saw more than 10 patients per clinic day in an APC compared to RRC (68.2% vs 39.5%, p = 0.0001). Of note, the ACGME revised guidelines from 2022 require at least one half day of clinic per week and two outpatient half days of clinic per week with at least 10 patients seen per session, so these minimum requirements were not consistently met by the included respondents, however these guidelines were implemented after most respondents graduated from residency. Furthermore, we found no significant differences in perceptions of clinic helpfulness or areas requiring more experience between respondents that saw more, or less, than 10 patients per clinic day. The number of patients seen in clinic may be influenced by external factors, such as the number of residents in clinic at a time, the total number of patients presenting to clinic that day, or whether the clinic was a full day or half day. It is important to note that our questionnaire did not document full days or half days in clinic, which should be considered when interpreting the number of patients seen per day. The lower clinical volume associated with RRC may be unavoidable in some situations, but seeing fewer patients in RRC can hopefully provide a more methodical way for residents to learn from experience, with more time for reflection between encounters. However, low volume likely detracts from the amount of education and efficiency received in clinic, and further research on how clinical volume affects preparedness for practice is needed to elucidate this relationship.

The positive reviews of an APC likely indicate the strengths of mentorship in refining clinical skills and knowledge, especially pertaining to physical exam skills, diagnosis, and treatment. The extent of faculty involvement in RRC varies by institution, which may affect the quality of this experience. Results of prior studies in other medical and surgical specialties emphasize the importance of having attendings who are invested in the residents’ education.8,9,20 Stepczynski et al.20 found that among medical residency programs, residents who identified faculty as role models were more likely to be satisfied with their clinic experiences. Yet, resident autonomy has been shown to increase resident confidence and competence.21 Therefore, fostering an environment that enables autonomy under the guidance of dedicated attendings appears to be the ideal environment for resident development.22

A main limitation of the present study is the relatively small sample size of orthopedic surgeons. This survey was disseminated via the AOAO, which limited distribution to predominantly DO-educated orthopedic surgeons. This introduced selection bias, but it was thought that one’s medical education and training background would not have a significant impact on their perspective as a practicing orthopedic surgeon. The graduation year among respondents ranged from 1980 to 2021, which introduced some degree of recall bias related to the time since graduation from residency. The number of clinic days per week did not account for half-day or full-day clinics, and it is possible that the number of half-day clinics varied between clinic types. This may have been a confounding variable that affected the number of patients seen per day in clinic. By relating questions to ACGME competencies, many surgical sub-competencies were omitted because they did not apply to a clinical setting. Thus, we did not comprehensively evaluate the impact of clinic on each sub-competency.

Future directions for this topic include studies that evaluate how RRC affects patient safety and satisfaction. This has been carried out in non-orthopedic surgical specialties,2,6,22-26 yet no similar studies have focused on RRC in orthopedic surgery. Such a study could provide a more holistic evaluation of RRC to ensure that both patient care and resident educational value are optimized.

Conclusions

The results of the present study provide novel evidence that RRC and APC are valued by practicing orthopedic surgeons for improving confidence in physical exam skills, confidence in making a diagnosis, and patient communication skills and empathy. A greater proportion indicated they needed more experience with an aspect of RRC than an APC; with billing, coding, and insurance as the most identified unfulfilled aspect for both clinic structures. By addressing these potential deficits, a more complete educational experience for the resident can be developed, to assist them in future clinical practice.

Tables

- Table 1. ACGME Core Competencies

- Table 2. Background information of respondents

- Table 3. Current practice information of respondents

- Table 4. Answers pertaining to clinic experience in residency

- Table 5. Subgroup analysis of clinic volume, post-graduate training, and setting of current practice

Figures

- Figure 1. Fellowship training among respondents.

- Figure 2. Respondent answers to specific areas of their clinic experience that were helpful to their current clinical practice.

- Figure 3. Respondent answers to aspects of their clinic experience that needed more attention.

References

- Van Heest AE, Armstrong AD, Bednar MS, et al. American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery’s Initiatives Toward Competency-Based Education. JB JS Open Access. 2022;7(2).

- Witherspoon L, Jalali S, Roberts MT. Resident-run urology clinics: A tool for use in competency-based medical education for teaching and assessing transition-to-practice skills. Can Urol Assoc J. 2019;13(9):E279-E284.

- Damewood RB, Blair PG, Park YS, Lupi LK, Newman RW, Sachdeva AK. “Taking Training to the Next Level”: The American College of Surgeons Committee on Residency Training Survey. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(6):e95-e105.

- Camp CL, Martin JR, Karam MD, Ryssman DB, Turner NS. Orthopaedic Surgery Residents and Program Directors Agree on How Time Is Currently Spent in Training and Targets for Improvement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(4):915-925.

- Wojcik BM, Fong ZV, Patel MS, et al. The Resident-Run Minor Surgery Clinic: A Pilot Study to Safely Increase Operative Autonomy. J Surg Educ. 2016;73(6):e142-e149.

- Wojcik BM, McKinley SK, Amari N, et al. A comparison of patient satisfaction when office-based procedures are performed by general surgery residents versus an attending surgeon. Surgery. 2019;166(1):116-122.

- Wojcik BM, McKinley SK, Fong ZV, et al. The Resident-Run Minor Surgery Clinic: A Four-Year Analysis of Patient Outcomes, Satisfaction, and Resident Education. J Surg Educ. 2021;78(6):1838-1850.

- Chen J, Lee E, El Eter L, Cooney CM, Broderick KP. A Systematic Review on the Implementation and Educational Value of Resident Aesthetic Clinics. Ann Plast Surg. 2022;89(2):152-158.

- Morris MP, Toyoda Y, Christopher AN, Broach RB, Percec I. A Systematic Review of Aesthetic Surgery Training Within Plastic Surgery Training Programs in the USA: An In-Depth Analysis and Practical Reference. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2022;46(1):513-523.

- Day KM, Zoog ES, Kluemper CT, et al. Progressive Surgical Autonomy Observed in a Hand Surgery Resident Clinic Model. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(2):450-457.

- Brandel MG, DʼSouza GF, Reid CM, Dobke MK, Gosman AA. Analysis of a Resident Aesthetic Clinic: Process for Rhinoplasty, Resident Experience, and Patient Satisfaction. Ann Plast Surg. 2017;78(5 Suppl 4):S175-s179.

- Walker J, Payne B, Clemans-Taylor BL, Snyder ED. Continuity of Care in Resident Outpatient Clinics: A Scoping Review of the Literature. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(1):16-25.

- Pyle JW, Angobaldo JO, Bryant AK, Marks MW, David LR. Outcomes analysis of a resident cosmetic clinic: safety and feasibility after 7 years. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;64(3):270-274.

- Qureshi AA, Parikh RP, Myckatyn TM, Tenenbaum MM. Resident Cosmetic Clinic: Practice Patterns, Safety, and Outcomes at an Academic Plastic Surgery Institution. Aesthet Surg J. 2016;36(9):Np273-280.

- Qureshi AA, Parikh RP, Sharma K, Myckatyn TM, Tenenbaum MM. Nonsurgical Facial Rejuvenation: Outcomes and Safety of Neuromodulator and Soft-Tissue Filler Procedures Performed in a Resident Cosmetic Clinic. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2017;41(5):1177-1183.

- Kraft CT, Harake MS, Janis JE. Longitudinal Assessment of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery Training in the United States: The Effect of Increased ACGME Case Log Minimum Requirements. Aesthet Surg J. 2019;39(4):NP76-NP82.

- Pu LL, Thornton BP, Vasconez HC. The educational value of a resident aesthetic surgery clinic: a 10-year review. Aesthet Surg J. 2006;26(1):41-44.

- Weissler JM, Carney MJ, Yan C, Percec I. The Value of a Resident Aesthetic Clinic: A 7-Year Institutional Review and Survey of the Chief Resident Experience. Aesthet Surg J. 2017;37(10):1188-1198.

- Varacallo MA, Wolf M, Herman MJ. Improving Orthopedic Resident Knowledge of Documentation, Coding, and Medicare Fraud. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(5):794-798.

- Stepczynski J, Holt SR, Ellman MS, Tobin D, Doolittle BR. Factors Affecting Resident Satisfaction in Continuity Clinic-a Systematic Review. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(8):1386-1393.

- Fillmore WJ, Teeples TJ, Cha S, Viozzi CF, Arce K. Chief resident case experience and autonomy are associated with resident confidence and future practice plans. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71(2):448-461.

- LaPorte DM, Tornetta P, Marsh JL. Challenges to Orthopaedic Resident Education. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2019;27(12):419-425.

- Oliver JB, Kunac A, McFarlane JL, Anjaria DJ. Association Between Operative Autonomy of Surgical Residents and Patient Outcomes. JAMA Surg. 2022;157(3):211-219.

- Resnick AS, Disbot M, Wurster A, Mullen JL, Kaiser LR, Morris JB. Contributions of surgical residents to patient satisfaction: impact of residents beyond clinical care. J Surg Educ. 2008;65(3):243-252.

- Taylor AL, Aravind P, Bhoopalam M, et al. A 10-Year Review of Surgical Outcomes at the Johns Hopkins and University of Maryland Resident Aesthetic Clinic. Aesthet Surg J Open Forum. 2022;4:ojac074.

- van der Leeuw RM, Lombarts KM, Arah OA, Heineman MJ. A systematic review of the effects of residency training on patient outcomes. BMC Med. 2012;10:65.