Matthew C Augusta, DO1; Gabriel DeOliviera, MS32; Timothy J Westbrooks, MD3; Brandon R Scott, MD3

1University of Kentucky Department of General Surgery

2University of New England College of Osteopathic Medicine

3University of Kentucky Department of Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine

DOI: 10.70709/4jzxbc4lxv

Abstract

Background

Traumatic acute carpal tunnel syndrome (ACTS) occurs in 4.5-9% of distal radius fractures, predominantly in women. Rapid diagnosis of ACTS with expedient operative release and fixation is critical to prevent permanent debilitating median nerve complications. It is important to perform serial examinations and provide adequate patient education while in the emergency department.

Case

A 75 y/o right hand dominant female who is dependent on a walker for ambulation with past medical history of hypertension, Parkinson’s disease, and deep vein thrombosis presented to the emergency department with left wrist pain after falling onto an outstretched left hand. On examination, she had bruising about the dorsal wrist. Initial two-point discrimination was less than 6mm in both the ulnar and radial distributions yet greater than 10mm in the median. Her digits were warm and well perfused. Radiographs demonstrated a dorsally displaced distal radius fracture with shortening and volar shear. Closed reduction under conscious sedation was performed yielding improved alignment on post-reduction films. Serial examinations revealed worsening median nerve function. She underwent emergent surgical carpal tunnel release and fixation with immediate postoperative improvement.

Discussion

While most distal radius fractures in patients greater than 65 can be managed nonoperatively, it is crucial to assess the fracture and goals of each patient individually, especially with radiographic findings concerning for median nerve compression. Delaying surgery, high energy trauma, injury severity, and fracture type have been associated with poor patient outcomes. The treatment of ACTS requires expedient surgical intervention. While there are similar functional scores and patient reported outcomes between hardware used, dorsal bridge plating has been shown to allow earlier weight bearing for walker dependent patients. This case report was written to highlight the importance of early recognition of ACTS in distal radius fractures, especially in the elderly who are often discharged quickly after closed reduction and splint application.

Keywords: Distal radius fracture, elderly, acute carpal tunnel syndrome, dorsal bridge plating

Introduction

The incidence of traumatic acute carpal tunnel syndrome (ACTS) has been reported to be 4.5-9% in distal radius fractures, with 73% of these occurring in women (1,2). ACTS is a progressive median nerve compression leading to loss of two-point discrimination. Traumatic ACTS often results from hemorrhage into the carpal tunnel, edema from a fracture, or decrease in carpal tunnel volume from impinging fragments of the fracture (3). Rapid diagnosis of ACTS requires expedient operative release with concomitant operative fixation of the fracture to reduce complications like chronic median nerve dysfunction and complex regional pain syndrome (4,5). Nonoperative management with closed reduction and splinting is still the prevalent treatment for distal radius fractures in patients over 65; however, each clinical encounter should be evaluated on an individual basis based on radiographic findings, patient factors, and physical exam (6,7). As patients can develop ACTS, it is important to continue serial examinations while in the emergency department as well as adequate patient education (3).

Case Presentation

A 75 y/o right hand dominant female with past medical history significant for hypertension, Parkinson’s disease on pharmacotherapy, and deep vein thrombosis presented to the emergency department with left wrist pain after falling onto an outstretched left hand while getting out of bed. She ambulates with a walker at baseline. On initial examination, she felt that her left hand and wrist were “asleep” and very painful. She had paresthesias in the median and ulnar distributions. She had a closed wrist deformity with bruising about the dorsal wrist. Initial two-point discrimination was less than 6mm in both the ulnar and radial distributions yet greater than 10mm in the median. Her digits were warm and well perfused with less than two- second capillary refill. She had limited motor function secondary to pain and kept her digits in a flexed position.

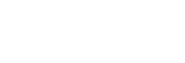

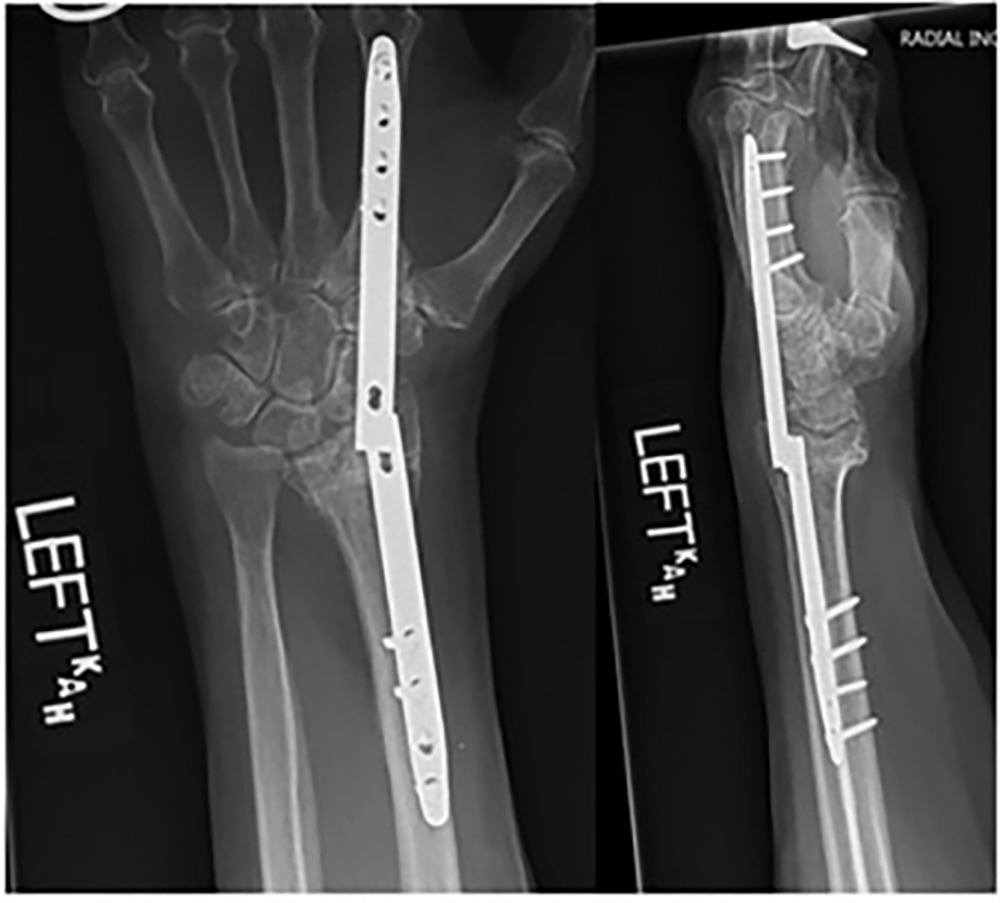

Radiographs demonstrated a dorsally displaced intra-articular distal radius fracture with shortening, volar shear, and intra-articular comminution further visualized on CT scan (Figures 1-2).

She underwent a closed manipulative reduction and was placed into a sugar tong splint under conscious sedation. Her post-reduction films demonstrated improved radiocarpal alignment (Figure 3).

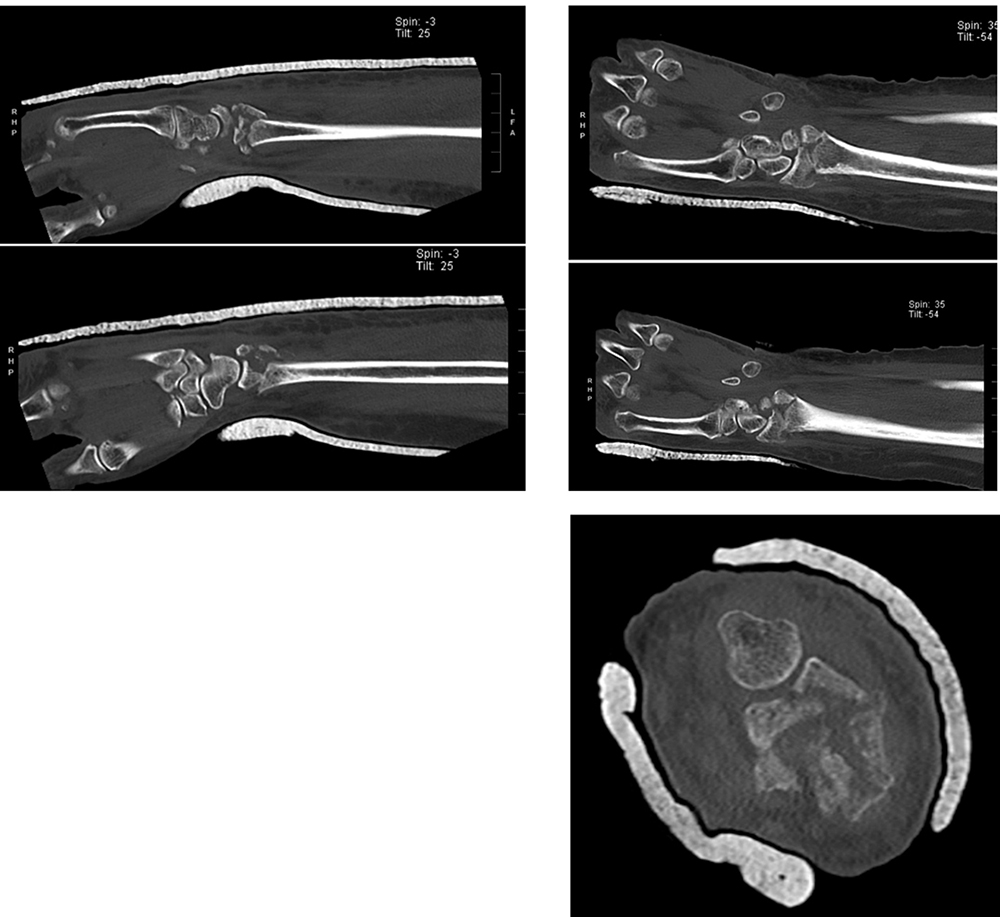

She was admitted to the orthopedic trauma service with plans for operative intervention. She was monitored with serial neurovascular examinations. The next morning, she began to have increased burning pain and numbness in the median nerve distribution. Her splint was loosened, and her wrist was elevated in an attempt to decrease the swelling. On repeat examination one hour later, there were increased paresthesias and burning isolated to the median nerve. She was taken to the operating room for emergent carpal tunnel release and operative fixation of her distal radius fracture with a dorsal spanning bridge plate. After the open carpal tunnel release, a dorsal approach was made over the second metacarpal. The dorsal spanning plate was passed proximally along the distal radius. Fluoroscopy was used to restore radial inclination and radial height with the bridge plate as well as restoration of length alignment and rotation via ligamentotaxis (Figure 4). A dorsal spanning plate was chosen based on the fracture pattern and instability as well as her need for a walker for ambulation.

Postoperatively she had immediate improvement in her subjective paresthesias as well as her two-point discrimination and motor function of her digits. Over the next several days, her two-point discrimination returned to baseline and symmetric to the contralateral. She was discharged to a subacute rehab facility. At her three-month follow-up, she was doing well. She did note that she started to have more motion at the wrist over the past week.

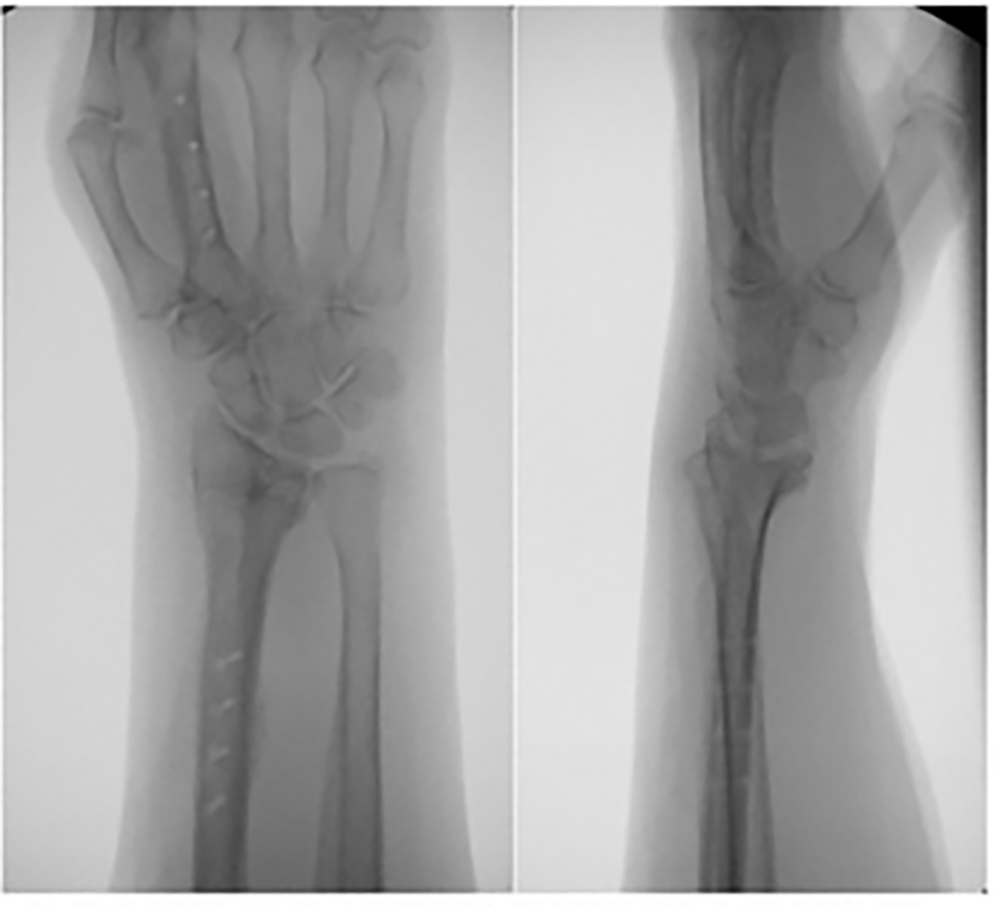

Radiographs demonstrated that the plate had broken, but she had satisfactory radiocarpal healing (Figure 5).

She had the dorsal plate removed one month later (Figure 6). Her postoperative range of motion was decreased 20% compared to the contralateral. She was discharged with a physical therapy plan to continue improving range of motion and strength.

Discussion

A review of PubMED and the University of Kentucky InfoKAT with the key words “distal radius fracture,” “elderly,” and “acute carpal tunnel” led to fewer than twenty publications. Additionally, a search with the key words “dorsal bridge plate” and carpal tunnel yielded few results. While the vast majority of distal radius fracture in patients greater than 65 can be managed nonoperatively, it is crucial to assess the fracture and goals of each patient individually, especially with radiographic findings concerning for median nerve compression. A delay in median nerve compression leads to worse patient outcome (3,8). There have been several reported predictors of ACTS including high energy trauma, degree of comminution, degree of displacement, and distance of reduction (8). The most associated risk factor is OTA Type C fractures likely due to the proximity of the median nerve to the articular surface as it passes under the flexor retinaculum (2).

It also is important to distinguish ACTS from median nerve neuropraxia (MNN). This is done primarily by monitoring the course of the injury. In the traumatic setting, ACTS usually results from hemorrhage, fracture edema, or fracture fragments (3). It typically presents as initial paresthesias with progressive loss of two-point discrimination, monofilament testing and grip strength in the medial nerve distribution. There can be eventual loss of thenar motor function (3,8). Compartment measuring can be performed but is often not necessary or practical. Pressures greater than 30 mmHg have been shown to be clinically significant (3,8). Imaging is often not needed, but advanced imaging can be obtained for operative planning. MNN can occur from any mechanism(s) that stretches the nerve. In the traumatic setting, it often occurs at the point of maximal displacement of the fracture. Thus at initial examination, the sensory abnormalities will be apparent and are likely not to progress (3). Compartment pressures would not be increased.

The treatment of ACTS requires surgical intervention as soon as possible. If done within 36 hours of ACTS onset, functional score outcomes have been excellent (9). When done in combination with internal fixation of the fracture, there is no reported differences in patient reported outcomes, symptom severity, and functional status compared with the outcomes of an elective carpal tunnel release, which indicates the effectivity of the intervention if done acutely (8).

There has not been a reported difference in which operative management is recommended. There are similar functional scores and patient reported outcomes for volar locking plates and dorsal bridge plating. It is important to consider patient factors and utilize patient shared decision making. In comminuted, intraarticular fractures, dorsal distraction plating has been shown to allow for restoration of radial height, radial inclination and volar tilt (10, 11). Additionally, dorsal bridge plating has been shown to allow earlier weight bearing for walker dependent patients which can help with patients who utilize assistive devices for ambulation or those with polytrauma (12). In our case, we chose the dorsal bridge plating method based on fracture pattern and patient needs.

Clinical Message

This case report was written to highlight the importance of early recognition of acute carpal tunnel syndrome in distal radius fractures. This is especially true in the elderly who are often discharged quickly after closed reduction and splint application.

Consent

Consent was obtained from the patient herself.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Jhattu, H., Klaassen, S., Ying, C., & Hussain, M. A. (2012). Acute carpal tunnel syndrome in trauma. European Journal of Plastic Surgery, 35(9), 639–646. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00238 012-0732-0

- Leow, Jun Min, et al. “The Rate and Associated Risk Factors for Acute Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Complicating a Fracture of the Distal Radius.” European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery & Traumatology, vol. 31, no. 5, 23 Apr. 2021, pp. 981–987, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-021-02975-5.

- Holbrook, Hayden S., et al. “Acute carpal tunnel syndrome and median nerve neurapraxia.” Orthopedic Clinics of North America, vol. 53, no. 2, Apr. 2022, pp. 197–203, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocl.2021.11.005.

- Pope, David, and Peter Tang. “Carpal Tunnel Syndrome and Distal Radius Fractures.” Hand Clinics, vol. 34, no. 1, 1 Feb. 2018, pp. 27–32, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0749071217301130?via%3Dihub, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hcl.2017.09.003.

- Shah, Kalpit N., et al. “Acute Carpal Tunnel Syndrome in Inpatients with Operative Distal Radius Fracture.” Orthopedics, vol. 42, no. 4, 28 May 2019, pp. 227–234, https://doi.org/10.3928/01477447-20190523-04.

- Cooper, Alexus M, et al. “Nonsurgical management of distal radius fractures in the elderly: Approaches, risks and limitations.” Orthopedic Research and Reviews, Volume 14, 15 Aug. 2022, pp. 287–292, https://doi.org/10.2147/orr.s348656.

- Kamal, Robin Neil, and Lauren Michelle Shapiro. “Practical Application of the 2020 Distal Radius Fracture AAOS/ASSH Clinical Practice Guideline: A Clinical Case.” Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, vol. 30, no. 9, 1 May 2022, pp. e714–e720, https://doi.org/10.5435/jaaos-d-21-01194. Accessed 6 May 2022.

- Gillig, Jonathan D, et al. “Acute Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Review of Current Literature.” The Orthopedic Clinic of North America, vol. 47, no. 3, 1 Jan. 2016.

- Samuel, Thomas D., et al. “Acute Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: Early Nerve Decompression and Surgical Stabilization for Bony Wrist Trauma.” Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Global Open, vol. 11, no. 4, 5 Apr. 2023, p. e4929,www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov pmc/articles /PMC10079339/, https://doi.org/10.1097/GOX.0000000000004929.

- Perlus, R., et al. “The use of dorsal distraction plating for severely comminuted distal radius fractures: A review and comparison to Volar Plate fixation.” Injury, vol. 50, June 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2019.03.052.

- Fares, Austin B. et al. Dorsal Bridge Plate for Distal Radius Fractures: A Systematic Review. Journal of Hand Surgery, Volume 46, Issue 7, 627.e1 – 627.e8

- Raducha, J. E., Hresko, A., Molino, J., Got, C. J., Katarincic, J., & Gil, J. A. (2022). Weight-Bearing Restrictions With Distal Radius Wrist-Spanning Dorsal Bridge Plates. The Journal of Hand Surgery, 47(2), 188.e1–188.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2021.04.008