Robleh A. Omar OMS41; Micah Jones, DO2

1Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine

2Kleinert and Kutz/University of Louisville Adult Hand, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Pediatric hand/upper extremity

DOI: http://doi.org/10.70709/so8qwmyie

Abstract

The Carpometacarpal (CMC) joint of the thumb is crucial for hand function and relies heavily on ligamentous stability. Osteoarthritis of the first CMC joint, also known as basilar thumb arthritis (BJA), is a common degenerative disease, particularly among the elderly and postmenopausal women. This paper aims to explore the effectiveness of nonoperative treatment modalities in managing BJA by offloading the basal joint. This is a comprehensive review of existing literature on nonoperative treatments for BJA, focusing on orthoses, activity modification, and ergonomic tools. The study involves a detailed analysis of clinical studies and reviews addressing the conservative management of BJA. Key treatment modalities, such as orthoses for joint stabilization, exercises for improving flexibility, and ergonomic tools for offloading the joint, are evaluated for their efficacy in pain relief and functional improvement. The findings of this review suggest modalities to offload the basal joint and improve daily function in patients with BJA. Orthoses provide joint stabilization and, while ergonomic modifications and exercises help offload the CMC joint, addressing the increased forces experienced by the joint. Despite the prevalence of BJA, there is a significant gap in research on conservative management, highlighting the need for further studies to optimize non-surgical treatment strategies.

Introduction

The Carpometacarpal (CMC) joint of the thumb is a saddle-shaped joint that relies heavily on ligamentous stability.

Osteoarthritis of the first CMC joint also known as basilar thumb arthritis, and basal joint arthritis, is a degenerative disease of the first CMC joint. Typical symptomatology includes pain at the base of the thumb with activities such as pinching and loading the basal joint. Pain is commonly caused by twisting doorknobs, opening jars, turning car keys among other common activities. In the context of basal joint arthritis, it’s crucial to consider the impact of hand positions on the integrity and stress levels experienced by the carpometacarpal (CMC) joint, particularly the dorsal CMC ligament complex. A flat hand position, often used in various daily activities, can place significant stress on the dorsal CMC ligament complex. This increased stress may exacerbate the symptoms of basal joint arthritis, leading to pain and further joint degeneration. Understanding and mitigating the stress on this ligament complex through ergonomic hand positioning and supportive orthotics can be beneficial in managing the condition and preventing further deterioration. The diagnosis of CMC osteoarthritis can be made with a history of pain at the basal joint, pain with physical examination maneuver sensitive for BJA (such as the lever test, grind test, or metcarpophalangeal extention test), and a positive radiographic reading1. Positive radiographic findings can include joint space narrowing, osteophytes, subchondral sclerosis, and subchondral cysts as described later in this paper. Radiographic imaging is also useful in determining the severity of the disease. In general treatment can be conservative with adjusting activities of daily living, or operative depending on factors such as symptom severity and the stage of the disease. For the sake of uniformity, this disease will be referred to as basal joint arthritis (BJA).

Epidemiology

BJA is a very common arthritis of the hand. In terms of prevalence, it is only second to distal interphalangeal joint (DIP) arthritis. BJA is seen in 25% of men and 40% of women over the age of 75 years old2. This disease is more common in women and Caucasians. Postmenopausal women in their fifth to sixth decade of life are at increased risk compared to men of similar age. This is thought to be due to hormonal influences2.

Pathoanatomy

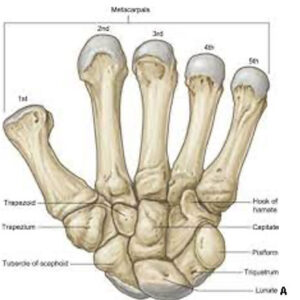

The pathophysiology of BJA is due to attenuation of volar, dorsal, and ulnar ligaments which have been named as primary stabilizers of the CMC joint. This joint has unique demands and is prone to arthritis due to many factors as presented by Ladd et al. These factors include joint instability, ligament laxity, and repetitive stress as key contributors. There is evolutionary pressure for a less constrained joint, delicate kinematics, and large compressive loads with activity, as well as hormonal influences related to sex and age3. Metacarpal phalangeal hyperextension deformity is a compensatory change that is commonly seen in patients. The patho-mechanics related to metacarpophalangeal (MCP) hyperextension play a significant role. The hyperextension of the MCP joint can lead to increased stress on the CMC joint, particularly when the dorsal ligament complex becomes attenuated. This attenuation reduces the stability of the CMC joint, often resulting in subluxation. Over time, this misalignment can worsen the wear and tear on the joint surfaces, exacerbating the symptoms of CMC arthritis. The first CMC joint is biconcave saddle joint. There are four articulations of the joint as can be seen in Figure 14. These consist of the Trapezimetacarpal, trapeziotrapezoid, scaphotreapezial, and the trapezium-index metacarpal.

Figure 1a4. First CMC Joint.

Figure 1b5 Ligaments of the first CMC joint

There is very important ligamentous stabilization that surrounds the CMC joint. The Anterior oblique ligament also known as the volar beak ligament is the primary stabilizing force that counteracts the tendency for the CMC joint to go into subluxation. The intermetacarpal ligament is the primary restraint for radial translation of the 1st metacarpal. The dorsal radial ligament is the primary restraint to dorsal dislocation and is commonly injured during dislocation of the CMC dorsally. The posterior oblique ligament is also visible in Figure 1b5 above. Interestingly due to the biomechanics of the saddle joint, pinch force is applied 13x more in the basal joint6. This is important to consider when discussing modalities to offload the joint.

Classification of BJA

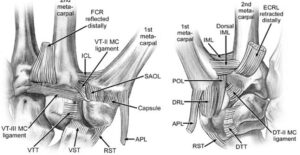

The most used classification system for Basilar thumb arthritis is the Eaton and Littler Classification system7. This system divides the progression of BJA into a stepwise progression ranging from stage 1- stage 4. Stage 1 consists of slight joint space widening, articular contours are normal, and there is <1/3 subluxation. Stage 2 shows slight narrowing of the CMC joint with sclerosis, significant capsular laxity, 1/3 subluxation of the joint, and osteophytes <2mm. Stage 3 displays mild narrowing of the CMC joint with osteophytes, >1/3 subluxation of the joint, and osteophytes > 2mm. Stage 4 has severe degenerative changes, major subluxation of the joint, very narrow joint space, cystic and sclerotic subchondral bone changes, significant erosion of the scaphotrapezial joint, and importantly there will be pantrapezial arthritis. Examples of these stages can be seen in Figure 28.

Figure 28 Eaton/Littler classification system

Imaging

Radiographic imaging is important to diagnose the stage of BJA. The recommended view is an AP, Lateral and Roberts view. The Roberts view is when the x-ray beam is centered on the trapezium and the metacarpal with the thumb flat on the table. The thumb will also be hyper pronated. This positioning can be seen in figure 39.

Figure 39 Roberts view x-ray positioning.

Treatment Options

Nonoperative treatment is the first line of treatment for BJA. Lopez et al. found in a long term outcomes cohort study that non-operative treatment strategies showed positive outcomes for no worsening of pain or limitations in activities of daily living after 12 months10. Treatment options that will not be discussed include injections, CMC arthroscopic debridement, 1st metacarpal osteotomy, trapeziectomy +/- ligament reconstruction, CMC arthrodesis, CMC denervation, and CMC prosthetic arthroplasty11. This paper will serve as a reference for modalities to offset the need for surgical intervention and alleviate symptoms while patients are still in the mild-moderate symptom stages. The offloading techniques can also be used by patients who have had injections, and prior surgical procedures as well.

According to a systematic review performed by Spaans Et al., There are only a few high-quality studies addressing the conservative treatment of BJA. These studies suggest some effect of orthoses and intra-articular hyaluronate or steroid injections12. Orthoses support the thumb in abduction and support inherent stability by maximizing the thumb web space. Pain management is achieved if the splint is worn for longer than three months. Daytime pain relief is possible even if only worn at night13. Examples of these splints can be seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4. CMC orthoses

Exercises are recommended to aid in improving joint flexibility and range of motion. These exercises are designed to strengthen the muscles around the CMC joint, improve joint stability, and reduce strain on the ligaments, particularly the dorsal ligament complex. By targeting the muscles that support the thumb, these exercises can help prevent MCP hyperextension, decrease the likelihood of subluxation at the CMC joint, and ultimately alleviate pain and slow the progression of arthritis. Exercises should be done routinely to maintain the benefits gained14. Various exercises exist but any exercise done should be done slowly and smoothly. Exercises should not cause pain and can be supplemented with rest and stretching15. Examples of some exercises can be seen in Figure 516.

Figure 5. Examples of Exercises for Increasing flexibility and range of motion

Regarding pinch strength, there are 3 major types of pinches which include tip pinch, palmar pinch, and lateral pinch (key pinch). Tip pinch is achieved by approximating the tip of the thumb with the index finger. Palmar pinch is achieved by approximating the tips of the thumb, index finger and middle finger. Lateral or key pinch is described clinically as the force generated while achieving thumb contact with the side of the index finger17. The ability to perform a lateral pinch is important for many activities of daily living and is critical to hand function. The CMC joint is vital to the function of lateral pinch and pain is often a limiting factor in gaining enough force in a lateral pinch to perform task such as writing, opening doors, opening jars, and performing activities of daily living. It has been found that maximum lateral pinch strength decreases 13.7% in patients with BJA, and maximum pinch strength can be achieved at 4-5cm of width18. This is important to consider when evaluating devices to augment the pinch.

Some activities that cause pain to patients include bottle opening and jar opening. These activities can be augmented with the assistance of devices that decrease the need for lateral pinch. An example of a device to augment bottle/jar opening can be seen in Figure 6a below. Notice how the lateral pinch width has been augmented to be wider into the 4-5 cm range. There are also devices available to offload the basal joint almost entirely through the implementation of accessory muscles to perform tasks that would otherwise be heavily reliant on lateral pinch and the basal joint. One of these devices can be seen below in Figure 6b. Note how the primary action that would be required to open the jar would be supination of the forearm thus offloading of the basal joint.

Figure 6a and Figure 6b (left to right)

Offloading the basal joint is important because the thumb CMC joint experiences up to 13 times the force transmitted at the tip of the thumb19. An arthritis cup is any cup that augments the grip so that the CMC joint is not stressed. These can include cups with a wider thick gripped handle, specially designed cups designed to drink from two hands, as well as handles that can be added to any thermos to augment the gripping experience. Examples of these respective modalities can be seen in Figure 7. These modalities are inexpensive and widely attainable for patients with online shopping or through brick and mortar department stores. When considering the effect of the lateral pinch on the CMC joint, it is clear to see how holding a conventional travel mug (such as the one pictured below) increases the lateral pinch force required for holding. Comparing that to a travel mug with a handle as also pictured in figure 7, it is evident that the force required to hold the mug is dispersed through the 2nd-5th digits and the basal joint is minimally required to bare any weight or exert force through lateral pinch.

Figure 7. Cups to offload the basal joint.

Another option to offload the basal joint that is especially useful for those patients who work at a desk is to use an ergonomic mouse and keyboard. The traditional mouse that is used with computers exacerbates the pinch mechanism which loads the first CMC joint. Pain can also be managed by using an ergonomic keyboard. By using an ergonomic mouse such as the one pictured in figure 8, the basal joint will be significantly offloaded by decreasing the pinching force that is required when using a standard mouse. Holding the keyboard in a position that maintains the webspace and abduction will also provide comfort. There is little research providing evidence to support the usage of these modalities, however it may be reasonable to attempt these changes as they are very low risk.

Figure 8. Ergonomic mouse and keyboard

Changes can also be made when the patient is writing. There are many different techniques to lessen the amount of strain that is placed upon the basal joint during the writing process. One of these techniques is to start to use wider grip pens and pencils that require decreased pinch strength to operate. There are also attachments that can be added to existing pens and pencils to facilitate decreased pinch strength as well. This can be applied to paintbrushes and toothbrushes as well. Making these minor adjustments with devices such as the ones seen below offload the basal joint and can make for an improved quality of life. Activities such as teeth brushing and writing are great targets for augmentation because these are typically activities that are undertaken multiple times daily. These can be seen in Figure 920,21. Finally, by changing the traditional grip of the pencil to hold the pencil between the 2nd and 3rd phalanges, there is a decreased load placed upon the first CMC joint and decreased pinch as well. This grip is demonstrated in Figure 9 below.

Figure 9. Basal joint hand instrument augmentation.

In today’s day and age, cell phone usage is one of the newest activities of daily living (ADL). Being able to operate a smartphone effectively and efficiently is a life skill that is very important for functioning in modern society. Unfortunately, many people who have BJA have difficulty operating modern smartphones due to the ever-increasing size of the latest models. As displayed in Figure 10 below, the standard way of holding the phone can cause stress to the basal joint. This stress results in pinch pain which is disruptive to everyday life. Offloading can be achieved by using a case that has a loop to pass your fingers through, as well as using a kickstand for the device when possible. The kickstand allows the content on the device to be viewed without requiring the user to physically hold the smartphone. These modalities can be added in the form of cases or stand-alone additions such as pop-sockets as can be seen in Figure 10. These modalities can be purchased online and at many department stores at relatively affordable prices.

Figure 10: Notice the alternate way of holding the smartphone by using a case that has a loop, the weight of the device is supported by alternative fingers.

Conclusion

BJA is a debilitating disease that has well defined operative interventional research. There is however a lack of research surrounding non-operative modalities to off load the first CMC joint. There is however strong research that links BJA with a decreasing lateral pinch strength. We have explored in the article the anatomy, pathophysiology, and non-operative treatment modalities to improve activities of daily living in patients afflicted with BJA. Non-operative modalities are the first line treatment for the management of this disease and should be implemented prior to surgical intervention. Many modalities to off load the basal joint were explored including orthoses, exercises, activity modification devices, ergonomic office supplies, changes to writing techniques and ergonomic cellphone cases/additions. At the heart of all these therapies is one of two key points. Either maximizing the amount of lateral pinch force that can be generated through optimizing lateral pinch width and off-loading the basal joint. There is a need for research on the efficacy of non-operative treatment modalities to recommend the best non-surgical management for patients and this could be an area of further exploration in the future.

References

- Model, Z., Liu, A. Y., Kang, L., Wolfe, S. W., Burket, J. C., & Lee, S. K. (2016). Evaluation of Physical Examination Tests for Thumb Basal Joint Osteoarthritis. Hand (N Y), 11(1), 108–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558944715616951

- Van Heest AE, Kallemeier P. Thumb carpal metacarpal arthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008 Mar;16(3):140-51. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200803000-00005. PMID: 18316712.

- Ladd, A. L., Weiss, A. -P. C., Crisco, J. J., Hagert, E., Wolf, J. M., Glickel, S. Z., & Yao, J. (2013). The Thumb Carpometacarpal Joint: Anatomy, Hormones, and Biomechanics. Instr Course Lect, 62, 165–179. PMID: 23395023. PMCID: PMC3935621.

- Ayhan, Çiğdem, and Egemen Ayhan. “Kinesiology of the wrist and the hand.” Comparative kinesiology of the human body. Academic Press, 2020. 211-282.

- Berger, R. A., & Weiss, A.-P. C. (2004). Hand Surgery (1st ed.) [Reproduced image]. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Higgenbotham, C., Boyd, A., Busch, M., Heaton, D., & Trumble, T. (2017). Optimal management of thumb basal joint arthritis: challenges and solutions. Orthop Res Rev, 9, 93–99. https://doi.org/10.2147/ORR.S138809

- Eaton RG, Lane LB, Littler JW, Keyser JJ. Ligament reconstruction for the painful thumb carpometacarpal joint: A long-term assessment. J Hand Surg Am. 1984;9:692–99

- Nuessle N., Vogelin E, Hirsiger S. (2021). Trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis – a stepwise therapeutic approach. Swiss Medical Weekly, 151(13), Article number 20465. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2021.20465

- Eaton Hand. (n.d.). Roberts view Xray beam angle 90 degrees, AP of the thumb. Eaton Hand. Retrieved from https://www.eatonhand.com/ray/ray012.htm

- Esteban Lopez, L. M. J., Hoogendam, L., Vermeulen, G. M., Tsehaie, J., Slijper, H. P., Selles, R. W., & Wouters, R. M. (2023). Long-Term Outcomes of Nonsurgical Treatment of Thumb Carpometacarpal Osteoarthritis: A Cohort Study. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 105(23), 1837–1845. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.22.01116

- Young, S. D., & Mikola, E. A. (2004). Thumb carpometacarpal arthrosis. Journal of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand, 4(2), 73-93.

- Spaans AJ, van Minnen LP, Kon M, Schuurman AH, Schreuders AR, Vermeulen GM. Conservative treatment of thumb base osteoarthritis: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Am. 2015 Jan;40(1):16-21.e1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.08.047. PMID: 25534834.

- Shridhar, V., & Williams, S. (2020). Basal thumb arthritis: Treatment strategies for managing pain. [Journal Name], 49(11), Page range. https://doi.org/10.31128/AJGP-06-20-5504

- 9 exercises to help hand arthritis. Arthritis Foundation. https://www.arthritis.org/health-wellness/healthy-living/physical-activity/other-activities/9-exercises-to-help-hand-arthritis. Accessed March 16, 2024.

- Health Education & Content Services. Active hand exercises. Mayo Clinic; 2010.

- Mayo Clinic. (n.d.). Arthritis exercises. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/arthritis/multimedia/arthritis-exercises/img-20008003

- Kong, S., Lee, K. S., Kim, J., & Jang, S. H. (2014). The Effect of Two Different Hand Exercises on Grip Strength, Forearm Circumference, and Vascular Maturation in Patients Who Underwent Arteriovenous Fistula Surgery. Annals of Rehabilitation Medicine, 38(5), 648-657. doi:10.5535/arm.2014.38.5.648

- Hock, Nancy, “Pinch Span and Force: Normative Data, Requirements for Functional Tasks and Life Roles, and the Influence of Carpometacarpal Joint Osteoarthritis” (2020). Dissertations. 3571. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/3571

- Berger AJ, Meals RA. Management of osteoarthrosis of the thumb joints. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40(4):843–850.

- Mayo Clinic. “Joint protection for people with hand arthritis.” Mayo Clinic, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/arthritis/in-depth/joint-protection/art-20546794, Accessed March 13, 2024

- Arthritis Supplies. (n.d.). BipGrip Pen Grip. Retrieved from https://www.arthritissupplies.com/bipgrip-pen-grip.html