Gabrielle Aluisio, OMS-III, MBA; Dr. Lindsey Tjiattas-Saleski, DO, MBA

Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine – Carolinas

DOI: 10.70709/1njnwlyldh

Abstract

Case: A 41-year-old female with Klippel-Trenaunay Syndrome (KTS) presented with worsening left lower extremity cellulitis and non-healing ulcers. Her medical history included epilepsy and hemiplegic migraines. Physical examination revealed ulcerations, erythema, and vascular malformations. Laboratory tests indicated leukocytosis and systemic inflammation. MRI confirmed vascular malformations and infection. The patient was treated with antibiotics and wound care, leading to improvement in her condition.

Conclusion: This case highlights the increased risk of cellulitis in patients with KTS due to vascular malformations and chronic venous insufficiency. It also underscores the importance of early intervention and a multidisciplinary approach to prevent recurrent cellulitis and related complications, such as osteomyelitis.

Keywords: Klippel-Trenaunay Syndrome, cellulitis, lymphedema, vascular malformations, osteomyelitis

Introduction

Klippel-Trenaunay Syndrome (KTS) is a congenital vascular disease classically characterized by a triad of cutaneous capillary malformations (port-wine stains), anatomically abnormal varicosities, and limb hypertrophy involving soft tissues and/or bones (1-4). First described by Maurice Klippel and Paul Trenaunay in 1900, KTS can be diagnosed clinically when at least two of these three components are present (1-3). The estimated frequency of occurrence is between 2 and 5 in 100,000, with no sex predominance (5)

Capillary hemangiomas, often present at birth as red or purple port-wine strains, are the most common vascular malformation in KTS, occurring in 98% of cases (6). The vascular abnormalities are slow-flow combined capillary-lymphatico-venous malformations devoid of arterio-venous fistulas seen in Parkes-Weber Syndrome (2,3). Anomalous superficial veins develop in the extremities, predisposing patients to cellulitis, pain, edema and an increased risk of thrombophlebitis (2,3). These manifestations, most commonly involving a unilateral lower extremity, contribute to significant morbidity, including chronic venous insufficiency and tissue overgrowth (7,8).

Orthopaedic conditions are common in KTS due to limb hypertrophy, with approximately 50% requiring surgical intervention (9). Among KTS patients, 84% experience limb-length discrepancy, 9% scoliosis, and 7% osteoporosis (9). Orthopaedic intervention was more likely in patients with lymphatic malformations and/or soft-tissue hypertrophy of the lower extremity or foot (9).

KTS is linked to somatic mutations in the phosphatidylinositol-4-5-bisphosphate 3 kinase catalytic subunit (PIK3CA) gene, which drives cellular overgrowth via the AKT/mTOR pathway(1,10). It is grouped under the PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndromes (PROS) spectrum which also includes other syndromes such as congenital lipomatous overgrowth, vascular malformation and epidermal naevi (CLOVE syndrome), megalencephaly-capillary malformation (MCAP), Hemihyperplasia Multiple Lipomatosis (HHML) (1,10,11).

Venous disease is a major source of morbidity in KTS, which affected limbs exhibiting complex reflux patterns, severe valvular incompetence, and other characteristics that are characterized by an advanced venous clinical severity (VCSS) and CEAP grade (12). Though arteriovenous malformations are common, intracranial AVMs are rare but, if present, may cause neurological complaints such as seizures, headaches, and progressive numbness (7).

Common symptoms of KTS may include pain, lymphedema, bleeding, stasis dermatitis, poor wound healing, and superficial thrombophlebitis. Less common manifestations include intraosseous vascular malformations and spina bifida (4,9). Skin complications such as ulceration, vascular ectasia, and infection occur in nearly 45% of patients with KTS, with cellulitis being a frequent manifestation (6,13,14). Up to 22% of patients with KTS report cellulitis (13).

Cellulitis presents as a warm, erythematous, edematous, poorly demarcated area as a result of a local bacterial infection of the skin or subcutaneous soft tissue affecting the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue, potentially moving into the bone, leading to osteomyelitis (15). Osteomyelitis is a serious infection of bone that can develop due to hematogenous dissemination, direct inoculation, or contiguous spread from an adjacent area of soft tissue infection (16).

A literature search showed that although cellulitis is a common complication for an uncommon disease, septicemia secondary to skin-related conditions is rarely reported, making this case significant. Additionally, KTS in regard to osteomyelitis risk progression is rarely discussed among literature.

Statement of Informed Consent

The patient was informed that data concerning the case would be submitted for publication, and the patient agreed.

Case Report

A 41-year-old Caucasian female with a history of KTS, epilepsy, and hemiplegic migraines presented to the emergency department with worsening left lower extremity cellulitis and non-healing ulcers that had been progressively worsening over two weeks (Figure 1). She initially noticed an ulcer on the lateral aspect of her left lower extremity, which progressively spread with increasing erythema. She reported a two-day history of escalating pain, erythema, and purulent drainage, accompanied by fever and generalized weakness. Relevant history includes diagnosis of epilepsy at age 2 following multiple grand mal seizures, which was treated with phenobarbital and later transitioned to topiramate and valproate. At age 35, she was formally diagnosed with KTS leading to a switch to lamotrigine for further seizure management.

On examination, the left dorsal foot and second toe exhibited warmth, erythema, induration, purulence, and tenderness. The left lateral ankle exhibited a stage III ulceration on the Wagner Classification System with full thickness tissue loss, exposed subcutaneous fat, and surrounding erythema. There was no exposed bone, tendon, or muscle. The left lower extremity showed a birthmark consistent with a faded port-wine stain, prominent venous and capillary discoloration, and cyst-like venous malformations (Figure 2).

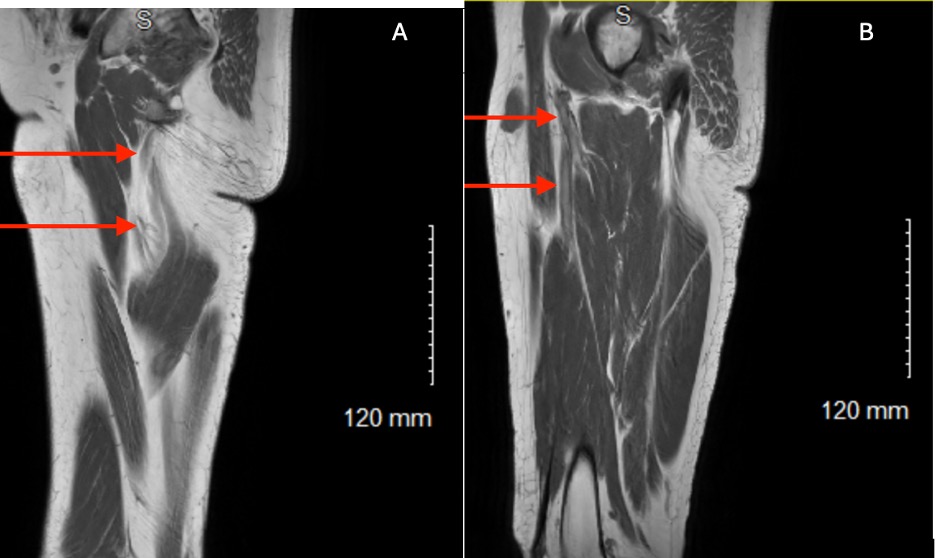

Laboratory results revealed leukocytosis [18.9 x 109/L (range: 4.5-11 x 109/L), elevated procalcitonin [59.35 ng/mL (range: <0.1 ng/mL)], and systemic signs of inflammation [102°F (range: 97-99°F)]. MRI of the left femur demonstrated vascular malformations within the vastus lateralis muscle and inflamed inguinal lymph nodes consistent with infection (Figure 3). Prior venous reflux studies confirmed superficial venous insufficiency of the left great saphenous vein.

She was treated with intravenous vancomycin and ceftriaxone, leading to an improvement in her cellulitis with concurrent wound care (figure 4). Neurological symptoms remained stable under lamotrigine therapy. Her wound was treated with pressure bandages, silver nitrate for chemical cautery, 1% hydrocortisone and 1% chloramphenicol compound cream for hyper granulation, along with compression stockings.

Discussion

Patients with KTS are at an increased risk for developing venous ulcers and cellulitis, which can progress to osteomyelitis and malignancy (17). Vascular malformations present in patients with KTS lead to lymphedema and venous insufficiency, which are two major risk factors for cellulitis (18).

Cyst-like lesions in the superficial skin layer of patients with KTS lead to chronic lymphatic leakage and bleeding on the skin surface leading to a breakdown of the skin barrier and an entry point for bacteria (13,14). Patients with chronic venous disease (CVD), such as KTS, may develop soft tissue infections even in the absence of gross skin breakdown (19). Vascular malformations lead to an increased presence of protein and nutrient rich lymphedema which may make the environment favorable to bacterial infection (14,19). Lymphedema results in sustained fluid accumulation, fat deposition, fibrosis, and impaired immune response (18,20). In some studies, up to 87% of lower limb cellulitis show lymphatic abnormalities on lymphoscintigraphy scans (18,21).

Additionally, patients with KTS are at increased risk for developing chronic wounds and ulcers, which act as a port of entry for bacteria (18,22). Chronic wounds often develop bacterial biofilms, delaying wound healing and increasing the risk of infection (18,23). Stasis dermatitis and lipodermatosclerosis from chronic venous insufficiency further heighten the risk of ulcers and infections (20). Compromised blood supply impairs wound healing to the lower extremities which, in turn, promotes the contiguous spread of infection to an adjacent area, such as bone (24).

Prevention of cellulitis in this patient population is difficult, however, conservative measures, such as compression stocking and limb elevation, may reduce lymphedema and venous insufficiency. Although cellulitis may respond to antibiotic therapy, patients with KTS often remain edematous, predisposing them to recurrent episodes with progressively worsening edema and pain (19). Recurrent cellulitis further damages the lymphatic system, leading to progressive lymphedema and increasing osteomyelitis risk (20). Early intervention is necessary to prevent complications such as abscess, bone deformity, systemic infection, septic arthritis, and tissue death (24).

KTS is a spectrum of clinical variations, with vascular malformations severity influencing prognosis. Treatment of patients with KTS is optimized with a multi-disciplinary team approach with care coordination.

Orthopaedic surgeons can provide a key role in managing KTS-related complications. Special considerations are needed when operating due to the risk of excessive bleeding from venous malformations as well as the prevalence of poor bone quality (25). Surgical options include limb-length discrepancy corrections, amputations, or synovectomies for intra-articular vascular malformations. Early synovectomy may slow the rapid destructive arthritis in patients with KTS (26). Total knee arthroplasty has been effective in treating arthritis with appropriate vascular assessments to determine the malformation severity (27,28). In regard to osteomyelitis management, Orthopaedic surgeons may perform surgical debridement, dead space management, appropriate antibiotic therapy, and soft tissue reconstruction, if necessary (29).

This case highlights the importance of increased awareness of KTS and the special considerations necessary when treating affected patients, particularly regarding their heightened risk of cellulitis and its progression to osteomyelitis. Although this patient did not present with classic orthopaedic manifestations of KTS, it remains essential for orthopaedic specialists to consider patients with KTS due to their underlying vascular malformations, which predispose them to orthopaedic complications not commonly associated with the syndrome, such as osteomyelitis.

References

- Naganathan S, Tadi P. Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber Syndrome. StatPearls [Internet]. 2023;

- Harnarayan P, Harnanan D. The Klippel-Trénaunay Syndrome in 2022: Unravelling Its Genetic and Molecular Profile and Its Link to the Limb Overgrowth Syndromes. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2022;18:201-209. doi:10.2147/vhrm.S358849

- Sung HM, Chung HY, Lee SJ, et al. Clinical Experience of the Klippel-Trenaunay Syndrome. Arch Plast Surg. 09.2015 2015;42(05):552-558. doi:10.5999/aps.2015.42.5.552

- Asghar F, Aqeel R, Farooque U, Haq A, Taimur M. Presentation and Management of Klippel-Trenaunay Syndrome: A Review of Available Data. Cureus. May 8 2020;12(5):e8023. doi:10.7759/cureus.8023

- Alwalid O, Makamure J, Cheng QG, et al. Radiological Aspect of Klippel-Trénaunay Syndrome: A Case Series With Review of Literature. Curr Med Sci. Oct 2018;38(5):925-931. doi:10.1007/s11596-018-1964-4

- Jacob AG, Driscoll DJ, Shaughnessy WJ, Stanson AW, Clay RP, Gloviczki P. Klippel-Trénaunay Syndrome: Spectrum and Management. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 1998/01/01/ 1998;73(1):28-36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-6196(11)63615-X

- Sadiq MF, Shuaib W, Tiwana MH, Johnson J-O, Khosa F. Klippel-Trénaunay Syndrome with Intracranial Arteriovenous Malformation: A Rare Presentation. Case Reports in Radiology. 2014/01/01 2014;2014(1):202160. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/202160

- Madhavan AA, Kim DK, Carr CM, et al. Association Between Klippel-Trenaunay Syndrome and Spontaneous Intracranial Hypotension: A Report of 4 Patients. World Neurosurg. Jun 2020;138:398-403. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2020.03.148

- Schoch JJ, Nguyen H, Schoch BS, et al. Orthopaedic diagnoses in patients with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. J Child Orthop. Oct 1 2019;13(5):457-462. doi:10.1302/1863-2548.13.190065

- Vahidnezhad H, Youssefian L, Uitto J. Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome belongs to the PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum (PROS). Experimental Dermatology. 2016/01/01 2016;25(1):17-19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/exd.12826

- Keppler-Noreuil KM, Rios JJ, Parker VER, et al. PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum (PROS): Diagnostic and testing eligibility criteria, differential diagnosis, and evaluation. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2015/02/01 2015;167(2):287-295. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.36836

- Delis KT, Gloviczki P, Wennberg PW, Rooke TW, Driscoll DJ. Hemodynamic impairment, venous segmental disease, and clinical severity scoring in limbs with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. J Vasc Surg. Mar 2007;45(3):561-7. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2006.11.032

- Anderson KR, Nguyen H, Schoch JJ, Lohse CM, Driscoll DJ, Tollefson MM. Skin-Related complications of Klippel–Trenaunay Syndrome: a retrospective review of 410 patients. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2021/02/01 2021;35(2):517-522. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.16999

- Kobayashi T, Fujino A, Furugane R, et al. Seasonal incidence of cellulitis in cystic lymphatic malformation and Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome. Global Pediatrics. 2023/09/01/ 2023;5:100071. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gpeds.2023.100071

- Brown BD, Watson KLH. Cellulitis. StatPearls [Internet]. 2023;

- Wald ER. Risk factors for osteomyelitis. Am J Med. Jun 28 1985;78(6b):206-12. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(85)90386-9

- Collins L, Seraj S. Diagnosis and treatment of venous ulcers. Am Fam Physician. Apr 15 2010;81(8):989-96.

- Ong BS, Dotel R, Ngian VJJ. Recurrent Cellulitis: Who is at Risk and How Effective is Antibiotic Prophylaxis? Int J Gen Med. 2022;15:6561-6572. doi:10.2147/ijgm.S326459

- Raju S, Tackett P, Neglen P. Spontaneous Onset of Bacterial Cellulitis in Lower Limbs with Chronic Obstructive Venous Disease. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 2008/11/01/ 2008;36(5):606-610. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2008.03.015

- Toro RE, Gaitán J, Acevedo AM, Oliveros E, Montenegro Arenas AC. Recurrent Cellulitis as Clinical Presentation of Klippel–Trénaunay Syndrome: A Case Report. Annals of Internal Medicine: Clinical Cases. 2024/02/01 2024;3(2):e230399. doi:10.7326/aimcc.2023.0399

- Soo JK, Bicanic TA, Heenan S, Mortimer PS. Lymphatic abnormalities demonstrated by lymphoscintigraphy after lower limb cellulitis. British Journal of Dermatology. 2008;158(6):1350-1353. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08423.x

- Akita S, Houbara S, Akatsuka M, Hirano A. Vascular anomalies and wounds. Journal of Tissue Viability. 2013;22(4):103-111. doi:10.1016/j.jtv.2013.08.001

- Roujeau J-C, Sigurgeirsson B, Korting H-C, Kerl H, Paul C. Chronic Dermatomycoses of the Foot as Risk Factors for Acute Bacterial Cellulitis of the Leg: A Case-Control Study. Dermatology. 2004;209(4):301-307. doi:10.1159/000080853

- Momodu I, Savaliya V. Osteomyelitis. StatPearls [Internet]. 2023;

- Nahas S, Wong F, Back D. A case of femoral fracture in klippel trenaunay syndrome. Case Rep Orthop. 2014;2014:548161. doi:10.1155/2014/548161

- Johnson JN, Shaughnessy WJ, Stans AA, et al. Management of knee arthropathy in patients with vascular malformations. J Pediatr Orthop. Jun 2009;29(4):380-4. doi:10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181a5b0b3

- Leal J, Davies AP, Selmi TAS, Neyret P. Knee Arthroplasty in Klippel-Trenaunay Syndrome : A Case Presentation with 5 years follow-up. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2008;23(4):623-626. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2006.12.116

- Li J, Lv G, Han Z, Xin X. Total knee arthroplasty in patients with Klippel Trenaunay syndrome and knee osteoarthritis: A case report and a literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). Jan 26 2024;103(4):e37000. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000037000

- Lari A, Esmaeil A, Marples M, Watts A, Pincher B, Sharma H. Single versus two-stage management of long-bone chronic osteomyelitis in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research. 2024/06/14 2024;19(1):351. doi:10.1186/s13018-024-04832-7