Gabriel DeOliveira, OMS 2026; Hunter Scott, OMS 2026; Benjamin Mugg, OMS 2026; Evan Lucey, OMS 2026; Geoffrey McCullen, MD, MS

University of New England College of Osteopathic Medicine

DOI: http://doi.org/10.70709/lin8gn4yjc

Abstract

Background

Failed Back Surgery Syndrome (FBSS) involves persistent pain and disability when surgical outcomes do not meet preoperative expectations and represents a significant and continuing burden for patients and providers. This study evaluates the possible role of preoperative autonomic dysfunction as a potential overarching modulator of FBSS through established comorbidities.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines. PubMed, Embase, and Scopus were searched from 2009 to August 2024. Included studies were screened for bias and quality using the QUIPS tool, Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, and USPSTF guidelines.

Results

A total of 21 studies (16 retrospective, 5 prospective) including over one million patients were analyzed. Chronic opioid therapy, COPD, psychiatric diagnosis, and diabetes emerged as the most prevalent comorbidities possibly associated with FBSS and may share a common underlying mechanism: autonomic dysfunction.

Conclusion

The findings suggest autonomic dysfunction may represent a physiological framework linking multiple risk factors of FBSS. Causality cannot be inferred from the current evidence, but it supports a hypothesis that autonomic dysfunction potentially modulates surgical outcomes through established comorbidities. Further investigation may guide improved preoperative stratification and treatment strategies. Future prospective studies should assess for diseases related to autonomic dysfunction and physiological evidence of preoperative autonomic imbalance pre-operatively.

Keywords: Failed Back Surgery Syndrome, Persistent Spinal Pain Syndrome Type 2, Chronic Pain, Autonomic Dysfunction, Preoperative Risk Factors, Spine Surgery

INTRODUCTION

Poor postoperative outcomes following spine surgery have been historically referred to as Failed Back Surgery Syndrome (FBSS), previously defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) as “lumbar spinal pain of unknown origin either persisting despite surgical intervention or appearing after surgical intervention for spinal pain originally in the same topographical location” (1). More recently FBSS has also been called Persistent Spinal Pain Syndrome Type 2 (PSPS-2), defined as chronic axial and/or limb pain occurring after spinal surgery (2). This new term further emphasizes the chronicity of the pain, allows more detailed subclassification, and incorporates an inclusive framework for future study (3). FBSS covers a wide range of conditions pertaining to persistent low back pain following one or more spinal surgeries that may or may not be accompanied by sciatica (4). A functional definition can simply be described as when the outcomes of spinal surgery do not meet the preoperative expectations of the patient and surgeon (5). Regardless of definition and despite technological advancements, FBSS remains a prevalent issue with a considerable negative impact on patients’ quality of life (6).

Chronic pain is linked to autonomic dysfunction, an imbalance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems (7,8). The autonomic nervous system (ANS) controls involuntary bodily functions, including pain modulation and tissue repair (9,10). Pathophysiology varies among body regions and involves disrupted afferent or efferent signaling between the central nervous system (CNS) and target organs (11). Dysfunction can arise intrinsically (from direct ANS nerve damage) or extrinsically (autonomic changes secondary to another disease) (11). Autonomic dysfunction is a prevalent health problem that remains underdiagnosed, undertreated, and underappreciated across healthcare systems (9). Recent research has suggested an association between FBSS and autonomic dysfunction (12,13).

Psychiatric diagnoses, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and others have been linked to FBSS and poor postoperative outcomes (14,15). For the purposes of this review, autonomic dysfunction-associated comorbidities refers to these diseases and conditions with established literature linking them to autonomic dysfunction. Autonomic dysfunction may be a modulator and potential overarching risk factor for FBSS, yet studies are lacking. To our knowledge, no studies have directly examined the relationship between autonomic dysfunction and FBSS specifically through preoperative comorbidities. Recognizing preoperative autonomic imbalance could impact operative management, and inform novel, multidisciplinary treatment strategies for FBSS that address both the autonomic and mechanical aspects of the patient.

The aim of this study is to evaluate the literature and determine the quantity, quality, and type of prognostic studies that found autonomic dysfunction-associated comorbidities to be associated with an increased risk for developing complications related to FBSS or FBSS directly. An additional aim of this study is to investigate the prevalence of autonomic dysfunction-related comorbidities found to be significantly associated with the development of FBSS or related complications and symptoms in the literature.

METHODS

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines (16). On August 4th, 2024, a systematic search of PubMed, Scopus, and EMBASE was performed on articles that included risk factors for PSPS Type 2 and the recently antiquated terminology FBSS. The following search protocols were applied to all three databases: “Failed back surgery syndrome risk factors”, “Post laminectomy syndrome risk factors”, “Chronic pain after spinal surgery risk factors”, “Chronic pain after back surgery risk factors”, “Persistent spinal pain syndrome type 2 risk factors”, “Failed back surgery syndrome” AND “risk factors”, “Post laminectomy syndrome” AND “risk factors”, “Chronic pain after spinal surgery” AND “risk factors”, “Chronic pain after back surgery” AND “risk factors”, and “Persistent spinal pain syndrome type 2” AND “risk factors”.

A PRISMA Flow Diagram depicting the process of identifying, including and excluding pertinent literature can be observed in Figure 1. Included were English written articles with adult patient populations (>18 years of age) retrieved using our specified search protocols. Excluded were studies that did not measure risk factors associated with autonomic dysfunction, measured outcomes that were not FBSS, evaluated other interventions when combined with spinal surgery. Outcomes of interest included the autonomic dysfunction-associated comorbidities found to be significant risk factors for the development of FBSS or FBSS associated risk factors. The presence of FBSS was based on the functional definition (5). For consistency with terminology used in the included studies, the term “risk factor” is used throughout this review to describe variables reported as being associated with postoperative complications or FBSS-related outcomes. These associations should not be interpreted as implying causality.

Autonomic Dysfunction Inclusion Criteria

There is no established list of diseases linked with autonomic dysfunction. Given the absence of an accepted diagnostic list, inclusion relied on literature-supported associations between comorbidities and ANS imbalance. As risk factors were identified, authors investigated if they were associated with autonomic dysfunction. These conditions include chronic opioid therapy (COT) (17,18), a psychiatric diagnosis (19,20), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (21), diabetes (22), obesity (23,24), peripheral vascular disease (25-27), osteoporosis (28), pain perception (30-32), fibromyalgia (33-35), hypertension (HTN) (36-38), hyperlipidemia (39,40), rheumatic disease (41), and tobacco use (42,43).

Data Extraction

Each retrieved study was reviewed by 3 independent reviewers (E.L., G.D., H.S.). Most articles were excluded during the initial title and abstract screening. References that could not be unequivocally excluded were evaluated by all three reviewers by full text report. In cases where a decision still could not be made, a consensus was reached after deliberation amongst all three reviewers. From the included articles, the following data was extracted: Study type, level of evidence, study population, purpose, measured outcomes, results. Because several included studies were authored by the same research group, we also referred to them by assigned study numbers (study 1, study 2, etc) to distinguish multiple publications from the same authors.

Study Quality

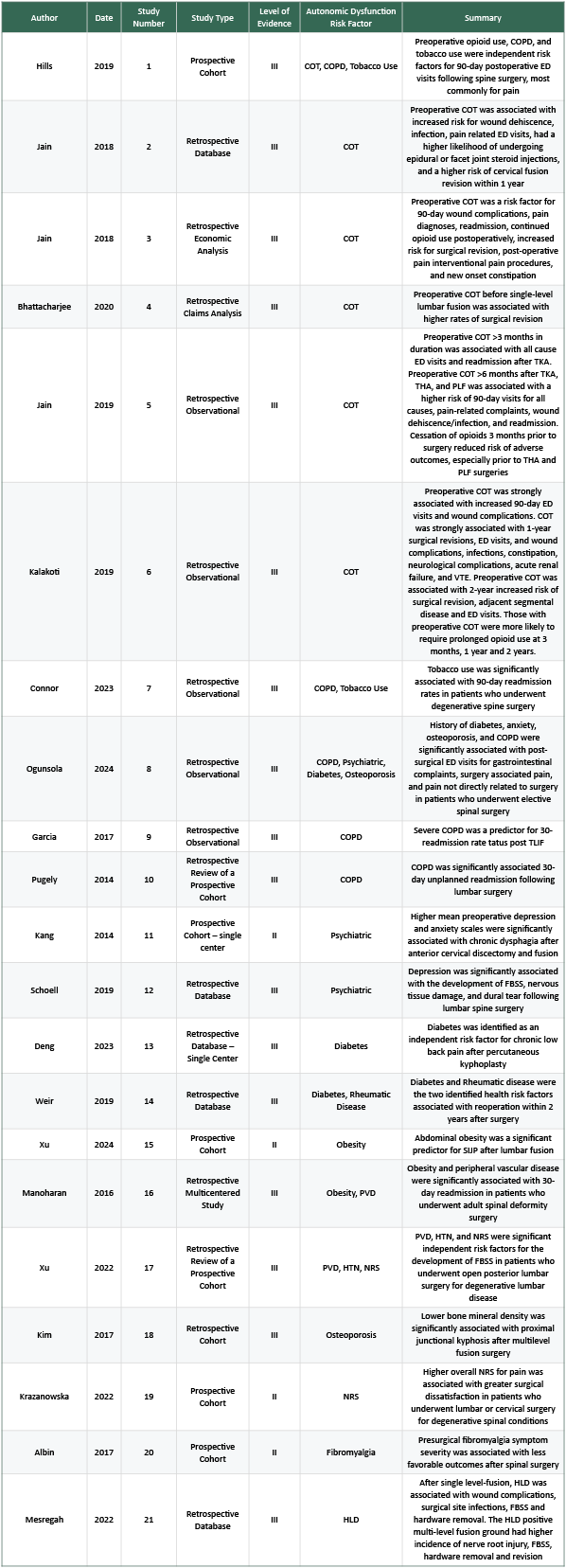

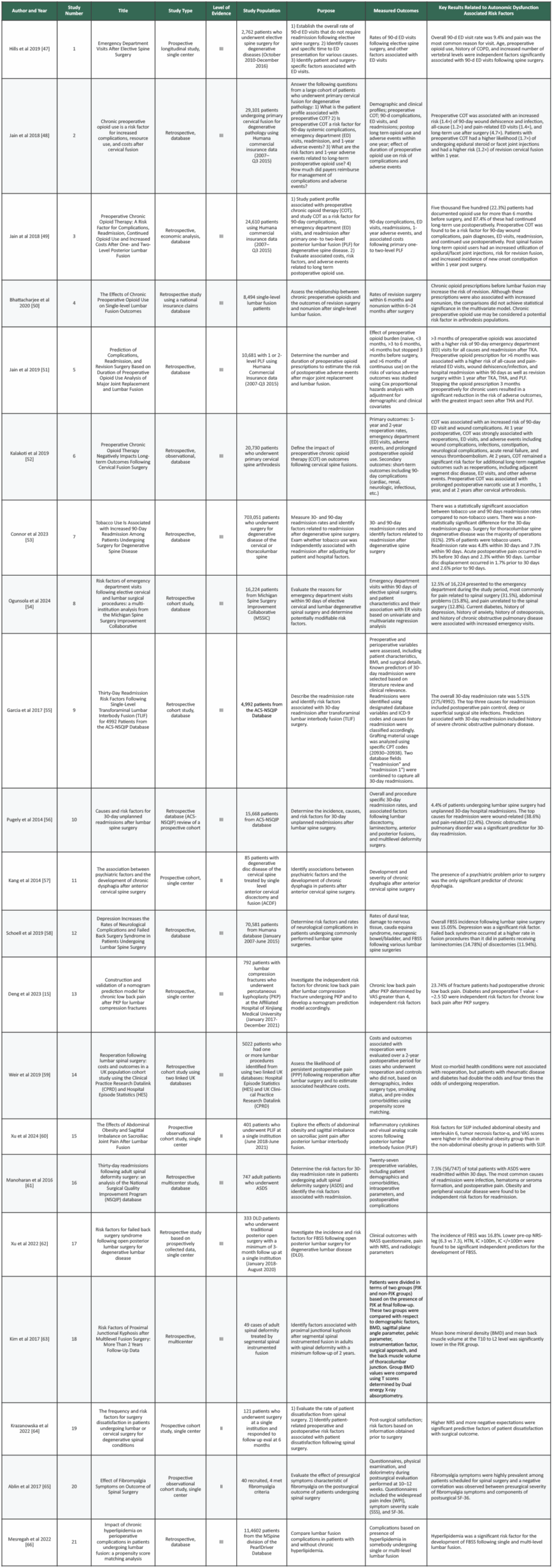

This literature review included 21 articles (Table 1, Supplementary Table 3). Each study received a level of evidence grading using the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force (44). The quality and risk for bias were assessed using the Quality in Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) tool and the Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) (45,46).

QUIPS assesses study quality and bias risk across six domains: 1) Study participation 2) Study attrition 3) Prognostic measurement 4) Outcome measurement 5) Confounding risk 6) Statistical Analysis and Reporting (45). Each domain is scored as LOW, MODERATE, or HIGH risk for bias. A study is low risk if all domains are rated as low with up to 1 moderate domain. Papers are deemed high risk if there are >3 domains rated as moderate or at least 1 high domain. Moderate risk studies fall between the criteria.

NOS assesses bias in non-randomized studies, scoring across three domains: 1) Selection of study groups 2) Comparability of study groups 3) Methods of outcome measurement (46). Each domain has three sub-criteria. Scores can range from 0-9, with scores >7 being classified as “good”, 2-6 being “fair”, and <1 being “poor”.

In this study, three independent reviewers (E.L., G.D., H.S.) assessed each article using QUIPS and NOS using separate standardized spreadsheets. Any discrepancies were discussed until a consensus was reached (Table1, Supplementary Table3).

Analysis

A descriptive analysis was conducted to summarize the characteristics of the included studies, including study type, level of evidence, study population, purpose, measured outcomes, methods/interventions, key results, and the prevalence of reported risk factors. Prevalence was determined by quantifying the number of studies that identified each risk factor. Due to heterogeneity in reported outcomes, statistical analysis for significant associations was not performed.

RESULTS

A total of 663 studies were identified. After removing duplicates, 345 studies remained for title and abstract screening, resulting in 61 studies for full-text review. Of these, 40 studies were excluded: 14 lacked an autonomic dysfunction-associated risk factor, 13 did not assess FBSS as the outcome, 4 were not in English, 2 included non-spine surgical populations, 2 were either adolescent or elderly only studies, and 5 were the wrong study type. Ultimately, 21 studies evaluating autonomic dysfunction-associated risk factors for FBSS were included (Figure1, Table1, Supplementary Table3). Although the term “risk factor” is used to maintain consistency with terminology, these variables represent associative findings, rather than proven causal predictors of FBSS.

The 21 included studies encompassed 1,029,086 patients with cohorts ranging from 40 (Ablin et al 2017) to 703,051 (Connor et al 2023) (65,53). Most studies were retrospective (76.2%, 16/21), of which 81.3% (13/16) were database analyses. The remaining retrospective studies included two single-center and one multicenter study. All five prospective studies were single-center.

The QUIPS assessment showed low risk of bias across most domains. Moderate risk of bias was found in the prognostic factor measurement domain for all studies due to inconsistent definitions of predictors.

The NOS assessment demonstrated moderate to high quality among included studies. Scores ranged from 6-7/9, with strong performance in the selection domain, but limited adjustment for confounders in comparability. Most scores were 2/3 in outcome assessment.

Abbreviations: COT=Chronic Opioid Therapy; COPD=Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; ED=Emergency Department; TKA=Total Knee Arthroplasty; THA=Total Hip Arthroplasty; PLF=Posterior Lumbar Fusion; VTE=Venous Thromboembolism; TLIF=Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion; FBSS=Failed Back Surgery Syndrome; SIJP=Sacroiliac Joint Pain; PVD=Peripheral Vascular Disease; HTN=Hypertension; NRS=Numeric Rating Scale (pain); HLD=Hyperlipidemia

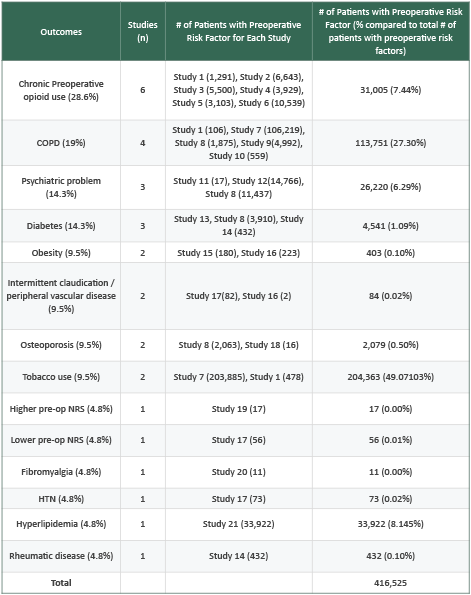

Risk factors linked to autonomic dysfunction with a significant relationship to FBSS development or postoperative complications related to the development of FBSS

Autonomic dysfunction-related risk factors found to have significant association with the development of FBSS or related postoperative complications included: chronic opioid therapy (COT), a psychiatric diagnosis, COPD, diabetes, obesity, peripheral vascular disease, osteoporosis, pain numerical rating scale (NRS), fibromyalgia, HTN, hyperlipidemia, rheumatic disease, and tobacco use. Although comorbidities were reported as “risk factors,” the retrospective nature of the evidence indicates correlation rather than proven risk. A detailed breakdown of these risk factors is provided in Table 2.

Chronic opioid therapy

Six studies (28.6%) including 31,005 patients with a preoperative history of chronic opioid therapy (COT) identified COT as a significant risk factor for postoperative FBSS-related complications. Hills et al 2019 (study 1), a prospective registry of 2,762 patients undergoing spine surgery for degenerative diseases, found that preoperative COT independently predicted 90-day ED visits (odds ratio [OR] 1.57, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] 1.17-2.12, p=.003) (47). Jain et al 2018 (Study 2), a retrospective review of 29,101 primary cervical fusion patients, found that preoperative COT for >6 months increased the risk of 90-day wound dehiscence and infection (OR 1.39, 95% CI 1.16-1.66, p<.001), pain-related ED visits (1.39,1.24-1.59, p<.001), epidural or facet joint injections within one year after surgery (1.68,1.47-1.92, p<.001), and repeat cervical fusion within one year compared to patients without preoperative COT (1.21,1.47-1.92, p=0.03) (48). Jain et al 2018 (Study 3), in 24,610 lumbar fusion patients, found that preoperative COT for >6 months increased the risk of 90-day wound complications (OR 1.19, 95% CI 1.05-1.35, p=.005), new pain diagnosis (1.10,1.02-1.19, p=.009), pain-related ED visits (1.31,1.15-1.49, p<0.001), and readmission for lumbar spine related pain diagnoses (1.80,1.24-2.57, p=.001) (49). Bhattacharjee et al 2020 (Study 4), using 8,494 database patients undergoing single-level lumbar fusion, found COT within 6 months of surgery independently increased 6-month revision risk (OR 1.45, 95% CI 1.11-1.90, p=.006) (50). Jain et al 2019 (Study 5), using a cohort of 10,681 posterior lumbar fusion patients, preoperative COT >6 months predicted all cause (hazard ratio [HR] 1.30, 95% CI 1.13-1.47, p<.001) and pain related ED visits (1.54, 1.28-1.86, p<.001), wound dehiscence and infection (1.30, 1.04-1.63, p<.02), 90-day hospital readmission (1.44, 1.19-1.74, p<.001) and 1-year revision surgery (1.42, 1.01-2.00, p=0.04) (51). Kalakoti et al 2019 (Study 6), a retrospective database analysis of 20,730 primary cervical arthrodesis patients, reported that 3-month preoperative COT increased the risk of 90-day ED visits (OR 1.25, p<.001), wound complications (1.24, p=.036) and reoperation rates at 1 and 2 years (1.17-1.21, all p=<0.05) (52).

COPD

Five studies (23.8%) including 113,192 patients with COPD found COPD to be a significant risk factor for postoperative complications related to the development of FBSS. Hills et al 2019 (Study 1), in a prospective cohort of 2,762 patients reported that a history of COPD had a significant association with 90-day ED visits following elective spine surgery for degenerative disease (OR 1.83, 95% CI 1.05-3.19, p=0.03) (47). Connor et al 2023 (Study 7), a retrospective database study of 703,051 degenerative spine surgery patients found that chronic lung disease was associated with a significantly increased risk of 30-day (OR 1.21, 95% CI 1.18-1.24, p<.0001) and 90-day (1.27, 1.24-1.30, p<.0001) readmission after surgery (53). Ogunsola et al 2024 (Study 8), a database study of 16,224 patients reported a history of COPD was associated with a significant risk of 90-day ED visits after elective cervical and/or lumbar surgery for degenerative pathology (relative risk [RR] 1.19, 95% CI 1.06-1.34, p=.003) (54). Garcia et al 2017 (Study 9), a retrospective database study of 4,992 transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF) patients reported a history of severe COPD was associated with a significantly increased risk of 30-day readmission after TLIF (OR 1.81, 95% CI 1.11-2.96, p=0.02) (54). Pugely et al 2014 (Study 10), a retrospective study of 15,668 lumbar spine surgery patients identified history of COPD as a significant risk factor for 30-day readmission (OR 1.73, 95% Cl 1.24-2.41, p<0.001) (56).

Psychiatric problems

Three studies (14.3%) including 26,220 patients with psychiatric problems identified a preoperative psychiatric diagnosis as a predictor of FBSS-related outcomes. Kang et al 2014 (study 11), a prospective cohort study of 85 cervical discectomy patients found the presence of a psychiatric diagnosis prior to surgery was the only significant predictor of postoperative chronic dysphagia (p=.005) (57). Schoell et al 2019 (study 12), a retrospective database study of 70,581 patients undergoing commonly performed lumbar spine procedures (initial posterior lumbar interbody fusion, transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion, anterior lumbar interbody fusion, posterolateral fusion, discectomy, laminectomy) found that depression was a significant risk factor for the development of FBSS (RR 1.74, 95% CI 1.67-1.80 p<.0001) (58). Ogunsola et al 2024 (study 8) also found that history of depression (RR 1.13, 95% Cl 1.03-1.25, p=.014) and anxiety (1.32, 1.19-1.46, p<.001) were associated with increased emergency department visits within 90 days of elective spinal surgery (54).

Diabetes

Three studies (14.3%) including 4,541 diabetic patients identified diabetes as a significant risk factor of postoperative complications related to FBSS. Deng et al 2023 (study 13), a retrospective analysis of 792 patients undergoing percutaneous kyphoplasty (PKP) identified diabetes as an independent risk factor for chronic low back pain postoperatively (OR 1.61, 95% CI 1.16-3.21) (15). Ogunsola et al 2024 (study 8) determined that diabetes was associated with increased 90-day ED visits in patients undergoing elective spinal surgery (RR 1.13, 95% Cl 1.01-1.26, p=.029) (54). Weir et al 2019 (study 14), a retrospective cohort study with 5,022 lumbar spine surgery patients found that diabetes had quadrupled the odds of undergoing reoperation (OR 4.70, 95% CI 1.41-15.74) (59).

Obesity

Two studies (9.5%) analyzing 403 obese patients reported obesity as a significant predictor of postoperative complications related to FBSS. Xu et al 2024 (study 15), a prospective observational cohort study of 401 patients undergoing posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF) found abdominal obesity to be significantly associated with increased postoperative sacroiliac joint pain (SIJP), visual analog scale (VAS) scores and levels of inflammatory markers (IL-6 and TNF-alpha) (p<0.05) (60). Manoharan et al 2016 (study 16), a retrospective study in 747 adult spinal deformity surgery patients found obesity to be an independent risk factor for 30-day readmission (OR 1.80, 95%CI 1.01-3.21, p=.047) (61).

Peripheral vascular disease

Two studies (9.5%) including 84 patients with peripheral vascular disease (PVD) identified PVD as a risk factor for FBSS and related postoperative complications. Xu et al 2022 (study 17), a retrospective study of 333 degenerative lumbar disease patients found that intermittent claudication with walking distance > 100 m (OR 4.07, 95%CI 1.75-9.47, p=.001) and waking distance ≤ 100 m (12.4, 5.54-27.92, p<.001) was an independent predictor for the development of FBSS (62). Manoharan et al 2016 (study 16) also identified preoperative PVD as an independent risk factor for 30-day readmission following adult spinal deformity surgery (OR 17.5, 1.10-288, p=.045) (61).

Osteoporosis

Two studies (9.5%) including 2,079 patients with osteoporosis or decreased bone mineral density (BMD) reported osteoporosis or BMD as significant risk factors for postoperative FBSS related complications. Ogunsola et al 2024 (study 8), found osteoporosis to be associated with increased 90-day ED visits after elective spine surgery (RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.09–1.34, p=.029) (54). Kim et al 2017 (study 18), a retrospective study of 49 patients with adult spinal deformity who underwent segmental spinal instrumental fusion (63). Patients were divided by presence of proximal junctional kyphosis (PJK) on follow up and mean bone mineral density was significantly lower in the PJK group compared to the group without PJK (PJK Mean T Score -2.30±0.85, non-PJK -1.01±0.67, p=.027) (63).

Tobacco use

Two studies (9.5%) analyzing 204,363 patients who smoke, reported tobacco use as a significant risk factor for postoperative complications related to FBSS. Connor et al 2023 (study 7) found that tobacco use increased 90-day readmission rates following degenerative spine surgery (OR 1.05, 95% CI1.03-1.07, p<.0001) (53). Hills et al 2019 (study 1) reported higher 90-day ED visits after spine surgery for degenerative disease among smokers 26.4% vs 17.8%, p=.001) (47).

Numeric Rating Scale (NRS)

Two studies (9.5%) examined pain severity’s association with FBSS through numerical rating scale (NRS). Xu et al 2022 (study 17) found lower pre-op NRS-leg (6.3 vs 7.3) predicted FBSS (p<0.05) (62). Krzanowska et al 2022 (study 19), a prospective study with 121 patients, reported that higher post-op NRS scores were associated with dissatisfaction 6 months post-operatively and negative expectations of surgical outcome (p<.001) (64).

Fibromyalgia

One study (4.8%) examined effects of surgery fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS), a risk factor for FBSS. 11 patients diagnosed with fibromyalgia were analyzed. Ablin et al 2017 (study 20) conducted a prospective observational cohort study of 40 patients measuring pre and postsurgical symptom severity scale (SSS) and widespread pain index (WPI) scores 10-12 weeks post operation on patients meeting criteria of fibromyalgia compared to those who did not. WPI decreased by 42.9% (p<.001) for FMS-negative patients (65). For FMS-positive patients, WPI decreased by 20.3% (р=0.04). SSS did not improve in FMS-positive patients (p=0.76). Presurgical WPI had a negative correlation with postoperative physical role functioning (r=-0.42, p=0.01) (65).

Hypertension (HTN)

One study (4.8%) with 73 patients with hypertension (HTN) examined the risk of FBSS in patients with HTN. Xu et al 2022 (study 17) identified hypertension as an independent predictor for development of FBSS following posterior lumbar surgery for DLD (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.10-4.51, p= 0.027) (62).

Hyperlipidemia

One study (4.8%) with 33,922 patients with hyperlipidemia examined the risk of FBSS in patients with hyperlipidemia. Mesreagah et al 2022 (study 21), a retrospective database study with 114,602 patients found hyperlipidemia to be a significant risk factor for the development of FBSS following single level and multi-level lumbar fusion [single-level fusion: 11.3% hyperlipidemic vs 9.5% non-hyperlipidemic (p<.001)] [multi-level fusion: 14.2% hyperlipidemic vs 11.5% non-hyperlipidemic (p<.001)] (66).

Rheumatic disease

One study (4.8%) with 432 patients with rheumatic disease examined rheumatic disease as a risk factor for postoperative complications related to FBSS. Weir et al 2019 (study 14) found that patients with preoperative rheumatic disease had double the odds of reoperation after lumbar spine surgery (OR 2.166, p<0.05) (59).

DISCUSSION

Failed Back Surgery Syndrome, also known as Persistent Spinal Pain Syndrome Type 2, severely impacts quality of life following spine surgery. This review explored whether preoperative conditions previously linked to autonomic imbalance were also associated with unfavorable surgical outcomes. Among autonomic dysfunction-associated comorbidities, COT was the most prevalent, followed by COPD, psychiatric diagnoses, and diabetes. Obesity, peripheral vascular disease, osteoporosis, pain (NRS), and tobacco use were less prevalent. Fibromyalgia, HTN, hyperlipidemia, and rheumatic disease were the least prevalent. While these findings reveal consistent associations, they do not confirm that autonomic dysfunction itself causes FBSS. Instead, they support the hypothesis that autonomic imbalance may serve as a unifying physiologic context influencing postoperative recovery in patients with these comorbidities.

Several studies have investigated the presence of autonomic dysfunction in FBSS patients (12,13). Sahin et al and El-Badawy et al evaluated sympathetic skin response (SSR) and pain intensity with VAS, finding statistically significant increased SSR latency in FBSS patients compared to controls, suggesting sympathetic nervous system dysfunction contributes to the intensity and chronicity of pain in FBSS (12,13). These studies excluded patients with comorbidities such as diabetes, renal disease, neuropathic disease, peripheral vascular disease, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, drug abuse, osteoporosis, psychiatric diagnoses and obesity, minimizing interference and supporting autonomic dysfunction as a factor in the pathophysiology of FBSS in the absence of these comorbidities (12,13). However, it remains uncertain how these comorbidities may impact the findings if present preoperatively.

Other reviews have demonstrated related findings. Masood et al found that patients with fibromyalgia develop more complications and worse overall postoperative outcomes after spine surgery, consistent with Albin et al (study 5) (65,67). Similarly, Baber and Erdek identified smoking, obesity, and psychiatric diagnoses as risk factors for FBSS development (1). Our study extends this by using these risk factors to indicate the potential presence of preoperative autonomic dysfunction. Wu et al analyzed the potential structural and non-structural causes of chronic pain after spinal surgery (CPSS), which is analogous with the functional definition of FBSS, and highlighted central sensitization’s role in chronic pain (68). They concluded that further research is warranted to investigate the role of spinal neuronal mechanisms into the pathogenesis of CPSS (68). Bordoni and Marelli suggested diaphragm dysfunction may contribute to FBSS due to inadequate carotid body baroceptor activation, leading to elevated sympathetic tone and heightened sensitization to pain (69). This complements the findings of our review further supporting autonomic dysfunction as a potential modulator of FBSS pathophysiology.

Therapeutic approaches targeting the sympathetic nervous system have shown efficacy in FBSS patients. Pulsed radiofrequency (PRF), although poorly understood, was as effective as a sympathetic block in patients with chronic regional pain syndrome (70). Like FBSS, their symptoms may be related to sympathetic overstimulation (70). Baronio et al utilized PRF in FBSS patients who failed standard therapy and showed significant reduction in lumbar and radicular pain, reported disability, and the number of analgesic drugs prescribed (71). Goudman et al found spinal cord stimulation significantly lowered heart and respiratory rates of FBSS patients, suggesting modulation of the ANS (72). While they were unable to properly control for or measure pain, these findings support ANS involvement in FBSS pathophysiology (72). Overall, these studies 1) further support a potential role of autonomic dysfunction contributing to the pathophysiology responsible for the pain in FBSS and 2) show that treatments aimed at decreasing sympathetic input can help patients suffering from FBSS.

Limitations of this review include the diagnostic ambiguity surrounding FBSS and PSPS-2. While these syndromes are clinically important, they remain diagnostically difficult to define and encompass a diverse patient population. This diversity may reflect differing degrees of autonomic imbalance. It is difficult to discern if patients included from studies with one listed risk factor, such as preoperative COT, truly have autonomic dysfunction. Still, recognizing this possible connection provides an opportunity to identify and assess risk factors and anticipate the clinical sequelae of autonomic dysfunction before spine surgery.

Additionally, most included studies evaluated short-term outcomes such as emergency department visits or readmissions within 90 days, rather than long-term pain persistence that defines FBSS. While such early complications may contribute to chronic pain syndromes, they do not independently establish FBSS. Therefore, the current evidence should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating and reflective of shared physiologic vulnerability rather than direct causation.

Methodological limitations include potential omission of studies not found in PubMed, Embase or SCOPUS, non-English publications, studies published before 2009, and studies reporting non-significant outcomes. In addition, randomized control trials (RCTs) examining FBSS were notably lacking, likely due to inherent impractical and ethical concerns with conducting RCTs in this surgical population. Third, our inclusion criteria relied heavily on the functional definition of FBSS (1,5). This allowed for a more accurate capture of surgical outcomes which may have been overlooked if we strictly focused on the IASP definition. However, this introduced heterogeneity and limits comparability across studies not using the functional definition. Finally, there is no established list of diseases or comorbidities associated with autonomic dysfunction, which limited standardized guiding for our inclusion criteria. Our approach introduces the potential for misclassification bias, however, this limitation is also a strength. Identification of comorbidities that may be associated with autonomic dysfunction provides a starting point for additional investigation, which could improve preoperative assessment and patient outcomes.

Future studies should aim to establish a comprehensive list of autonomic dysfunction-related comorbidities. While studies identifying autonomic dysfunction in FBSS patients exist, specific examination of a preoperative population is lacking. Prospective studies should evaluate preoperative autonomic function, utilizing HRV or SSR, without excluding comorbidities to assess their impact on the development of FBSS. If autonomic dysfunction is truly a common denominator among the established risk factors, it’s identification would benefit and optimize preoperative management, patient selection, and further aid in refinement of FBSS treatment strategies.

Conclusions

Autonomic dysfunction may provide a physiologic framework through which established comorbidities influence postoperative recovery and could contribute to poor outcomes after spinal surgery. Although we are not the first to propose this relationship, our review is the first to examine it through the lens of preoperative comorbidities. We propose that many established FBSS risk factors possibly share a common central mechanism: autonomic dysfunction. Despite the absence of an established list of autonomic dysfunction-associated diseases, we reframed the current evidence and highlight future directions. The evidence supports a hypothesis that systemic autonomic imbalance may modulate postoperative recovery. While it does not directly establish autonomic dysfunction as an independent risk factor, it highlights a potential association that should be investigated. Prospective studies using objective measures could clarify a relationship between autonomic dysfunction and FBSS and are necessary to validate this potential link. Insights may enhance preoperative risk stratification and open new avenues for FBSS therapeutic interventions. Additionally, raising awareness among spine surgeons, anesthesiologists and health professionals is essential to increase advocacy and improve outcomes for this complex patient population. Addressing FBSS through autonomic dysfunction may significantly improve outcomes and quality of life.

Supplementary Material

Table 3 provides a comprehensive evaluation of the included studies incorporating population, purpose, measured outcomes, and key results related to autonomic dysfunction associated risk factors.

References

- Baber Z, Erdek MA. Failed back surgery syndrome: current perspectives. J Pain Res. 2016 Nov 7;9:979-987. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S92776. PMID: 27853391; PMCID: PMC5106227.

- van de Minkelis, J., Peene, L., Cohen, S. P., Staats, P., Al-Kaisy, A., Van Boxem, K., Kallewaard, J. W., & Van Zundert, J. (2024). 6. Persistent spinal pain syndrome type 2. Pain practice: the official journal of World Institute of Pain, 24(7), 919–936. https://doi.org/10.1111/papr.13379

- Nick Christelis, Brian Simpson, Marc Russo, Michael Stanton-Hicks, Giancarlo Barolat, Simon Thomson, Stephan Schug, Ralf Baron, Eric Buchser, Daniel B Carr, Timothy R Deer, Ivano Dones, Sam Eldabe, Rollin Gallagher, Frank Huygen, David Kloth, Robert Levy, Richard North, Christophe Perruchoud, Erika Petersen, Philippe Rigoard, Konstantin Slavin, Dennis Turk, Todd Wetzel, John Loeser, Persistent Spinal Pain Syndrome: A Proposal for Failed Back Surgery Syndrome and ICD-11, Pain Medicine, Volume 22, Issue 4, April 2021, Pages 807–818, https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnab015

- Chin-wern Chan, Philip Peng, Failed Back Surgery Syndrome, Pain Medicine, Volume 12, Issue 4, April 2011, Pages 577–606, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01089.x

- Alexis Waguespack, Jerome Schofferman, Paul Slosar, James Reynolds, Etiology of Long-term Failures of Lumbar Spine Surgery, Pain Medicine, Volume 3, Issue 1, March 2002, Pages 18–22, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1526-4637.2002.02007.

- Daniell JR, Osti OL. Failed Back Surgery Syndrome: A Review Article. Asian Spine J. 2018;12(2):372-379. doi:10.4184/asj.2018.12.2.372

- Yeater TD, Clark DJ, Hoyos L, Valdes-Hernandez PA, Peraza JA, Allen KD, Cruz-Almeida Y. Chronic Pain is Associated With Reduced Sympathetic Nervous System Reactivity During Simple and Complex Walking Tasks: Potential Cerebral Mechanisms. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks). 2021 Jul 7;5:24705470211030273. doi: 10.1177/24705470211030273. PMID: 34286166; PMCID: PMC8267022.

- Koenig, Julian Dr. sc. hum.; Loerbroks, Adrian PD Dr. sc. hum.; Jarczok, Marc N. Dr. sc. hum.; Fischer, Joachim E. MD, MSc; Thayer, Julian F. PhD. Chronic Pain and Heart Rate Variability in a Cross-Sectional Occupational Sample: Evidence for Impaired Vagal Control. The Clinical Journal of Pain 32(3):p 218-225, March 2016. | DOI: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000242

- Sánchez-Manso JC, Gujarathi R, Varacallo MA. Autonomic Dysfunction. [Updated 2023 Aug 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430888/

- Theocharidis G, Veves A. Autonomic nerve dysfunction and impaired diabetic wound healing: The role of neuropeptides. Auton Neurosci. 2020 Jan;223:102610. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2019.102610. Epub 2019 Nov 26. PMID: 31790954; PMCID: PMC6957730.

- Goldberger JJ, Arora R, Buckley U, Shivkumar K. Autonomic Nervous System Dysfunction: JACC Focus Seminar. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Mar 19;73(10):1189-1206. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.12.064. PMID: 30871703; PMCID: PMC6958998.

- Sahin N, Müslümanoğlu L, Karataş O, Cakmak A, Ozcan E, Berker E. Evaluation of sympathetic response in cases with failed back surgery syndrome. Agri. 2009;21(1):10-15.

- El-Badawy, M. A., & El Mikkawy, D. M. (2016). Sympathetic Dysfunction in Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain and Failed Back Surgery Syndrome. The Clinical journal of pain, 32(3), 226–231. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000250

- Schoell, Kyle BA; Wang, Christopher BS; D’Oro, Anthony BA; Heindel, Patrick BA; Lee, Larry MD; Wang, Jeffrey C. MD; Buser, Zorica PhD. Depression Increases the Rates of Neurological Complications and Failed Back Surgery Syndrome in Patients Undergoing Lumbar Spine Surgery. Clinical Spine Surgery 32(2):p E78-E85, March 2019. | DOI: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000000730

- Deng GH. Construction and validation of a nomogram prediction model for chronic low back pain after PKP for lumbar compression fractures. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102(43):e34752. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000034752

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. Published 2021 Mar 29. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71

- Kienbaum P, Heuter T, Michel MC, Scherbaum N, Gastpar M, Peters J. Chronic mu-opioid receptor stimulation in humans decreases muscle sympathetic nerve activity. Circulation. 2001;103(6):850-855. doi:10.1161/01.cir.103.6.850

- Roberts RL, Garland EL. Association between opioid use disorder and blunted heart rate variability among opioid-treated chronic pain patients. Addict Biol. 2022;27(6):e13230. doi:10.1111/adb.13230

- Carnevali L, Mancini M, Koenig J, et al. Cortical morphometric predictors of autonomic dysfunction in generalized anxiety disorder. Auton Neurosci. 2019;217:41-48. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2019.01.001

- Sgoifo A, Carnevali L, Alfonso Mde L, Amore M. Autonomic dysfunction and heart rate variability in depression. Stress. 2015;18(3):343-352. doi:10.3109/10253890.2015.1045868

- van Gestel AJ, Steier J. Autonomic dysfunction in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). J Thorac Dis. 2010;2(4):215-222. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2010.02.04.5

- Vinik AI, Maser RE, Mitchell BD, Freeman R. Diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(5):1553-1579. doi:10.2337/diacare.26.5.1553

- Sant Anna Junior Md, Carneiro JR, Carvalhal RF, et al. Cardiovascular Autonomic Dysfunction in Patients with Morbid Obesity. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2015;105(6):580-587. doi:10.5935/abc.20150125

- Fidan-Yaylali G, Yaylali YT, Erdogan Ç, et al. The Association between Central Adiposity and Autonomic Dysfunction in Obesity. Med Princ Pract. 2016;25(5):442-448. doi:10.1159/000446915

- Nattero-Chávez L, Redondo López S, Alonso Díaz S, et al. Association of Cardiovascular Autonomic Dysfunction With Peripheral Arterial Stiffness in Patients With Type 1 Diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(7):2675-2684. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-02729

- Khalaf K, Jelinek HF, Robinson C, Cornforth DJ, Tarvainen MP, Al-Aubaidy H. Complex nonlinear autonomic nervous system modulation link cardiac autonomic neuropathy and peripheral vascular disease. Front Physiol. 2015;6:101. Published 2015 Mar 27. doi:10.3389/fphys.2015.00101

- Vinik AI, Ziegler D. Diabetic cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy. Circulation. 2007;115(3):387-397. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.634949

- Tosun A, Doğru MT, Aydn G, et al. Does autonomic dysfunction exist in postmenopausal osteoporosis?. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;90(12):1012-1019. doi:10.1097/PHM.0b013e31822dea1a

- Sohn R, Assar T, Kaufhold I, et al. Osteoarthritis patients exhibit an autonomic dysfunction with indirect sympathetic dominance. J Transl Med. 2024;22(1):467. Published 2024 May 16. doi:10.1186/s12967-024-05258-9

- McBenedict B, Petrus D, Pires MP, et al. The Role of the Insula in Chronic Pain and Associated Structural Changes: An Integrative Review. Cureus. 2024;16(4):e58511. Published 2024 Apr 18. doi:10.7759/cureus.58511

- Overmann L, Schleip R, Anheyer D, Michalak J. Myofascial release for adults with chronic neck pain and depression. Acta Psychol (Amst). 2024;247:104325. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104325

- Jose Paz Solis, Cristian Rizea, Rafael Martínez-Marín, Javier Díaz De Terán, María Román De Aragón, Beatriz Mansilla, Heleen Scholtes, Que Doan, Ismael Huertas, P157 SPINAL CORD STIMULATION AS A HOLISTIC TREATMENT FOR PAINFUL DIABETIC PERIPHERAL NEUROPATHY (PDPN): OUTCOMES FROM THE INSPIRE STUDY, Neuromodulation: Technology at the Neural Interface, Volume 28, Issue 1, Supplement, 2025, Page S261, ISSN 1094-7159, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurom.2024.09.394.

- Kingsley JD. Autonomic dysfunction in women with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14(1):103. Published 2012 Feb 20. doi:10.1186/ar3728

- Mahroum N, Shoenfeld Y. Autoimmune Autonomic Dysfunction Syndromes: Potential Involvement and Pathophysiology Related to Complex Regional Pain Syndrome, Fibromyalgia, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Silicone Breast Implant-Related Symptoms and Post-COVID Syndrome. Pathophysiology. 2022;29(3):414-425. Published 2022 Jul 28. doi:10.3390/pathophysiology29030033

- Staud R. Autonomic dysfunction in fibromyalgia syndrome: postural orthostatic tachycardia. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2008;10(6):463-466. doi:10.1007/s11926-008-0076-8

- Dissanayake HU, Skilton MR, Polson JW. Autonomic dysfunction in programmed hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2019;33(4):267-276. doi:10.1038/s41371-018-0142-2

- Cuspidi C, Carla S, Tadic M. Sleep, hypertension, and autonomic dysfunction. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2020;22(8):1491-1493. doi:10.1111/jch.13952

- Inanc IH, Sabanoglu C. The relationship of masked hypertension with autonomic dysfunction and cardiometabolic parameters: a case-control study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2022;26(17):6265-6272. doi:10.26355/eurrev_202209_29650

- Lohman, T., Kapoor, A., Engstrom, A.C., Shenasa, F., Nguyen, A., Alitin, J.P.M., Gaubert, A., Rodgers, K.E., Bradford, D., Mather, M., Han, D., Head, E., Thayer, J.F. and Nation, D.A. (2024), Central Autonomic Dysfunction and Plasma Ab42/40. Alzheimer’s Dement., 20: e089443. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.089443

- Upadhyay, S., Mazumder, A., Pentela, B., Bansal, P., Agarwal, N., & Baghel, D. S. (2025, January 1). Immunological implications in diabetes: A review on various diseases and Conditions. Natural Products Journal, The. https://www.benthamdirect.com/content/journals/npj/10.2174/0122103155298605240303181317

- Koopman FA, Tang MW, Vermeij J, et al. Autonomic Dysfunction Precedes Development of Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Prospective Cohort Study. EBioMedicine. 2016;6:231-237. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.02.029

- Middlekauff HR, Park J, Moheimani RS. Adverse effects of cigarette and noncigarette smoke exposure on the autonomic nervous system: mechanisms and implications for cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(16):1740-1750. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.06.1201

- Makhoul N, Avivi I, Barak Lanciano S, et al. Effects of Cigarette Smoking on Cardiac Autonomic Responses: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(22):8571. Published 2020 Nov 19. doi:10.3390/ijerph17228571

- Manchikanti L. Comment on Proposed LCD for Pain Management. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coverage/DeterminationProcess/Downloads/Manchikanti_comment.pdf. Accessed May 21, 2025.

- Hayden JA, van der Windt DA, Cartwright JL, Côté P, Bombardier C. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(4):280-286. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00009

- Pope D, Bruce N. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analysis. University of Liverpool; 2003. Accessed May 21, 2025. https://www.evidencebasedpublichealth.de/download/Newcastle_Ottowa_Scale_Pope_Bruce.pdf

- Hills JM, Khan I, Sivaganesan A, et al. Emergency Department Visits After Elective Spine Surgery. Neurosurgery. 2019;85(2):E258-E265. doi:10.1093/neuros/nyy445

- Jain N, Brock JL, Phillips FM, Weaver T, Khan SN. Chronic preoperative opioid use is a risk factor for increased complications, resource use, and costs after cervical fusion. Spine J. 2018;18(11):1989-1998. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2018.03.015

- Jain N, Phillips FM, Weaver T, Khan SN. Preoperative Chronic Opioid Therapy: A Risk Factor for Complications, Readmission, Continued Opioid Use and Increased Costs After One- and Two-Level Posterior Lumbar Fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2018;43(19):1331-1338. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000002609

- Bhattacharjee S, Pirkle S, Shi LL, Lee MJ. The Effects of Chronic Preoperative Opioid Use on Single-level Lumbar Fusion Outcomes. Clin Spine Surg. 2020;33(8):E401-E406. doi:10.1097/BSD.0000000000000953

- Jain N, Brock JL, Malik AT, Phillips FM, Khan SN. Prediction of Complications, Readmission, and Revision Surgery Based on Duration of Preoperative Opioid Use: Analysis of Major Joint Replacement and Lumbar Fusion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101(5):384-391. doi:10.2106/JBJS.18.00502

- Kalakoti P, Volkmar AJ, Bedard NA, Eisenberg JM, Hendrickson NR, Pugely AJ. Preoperative Chronic Opioid Therapy Negatively Impacts Long-term Outcomes Following Cervical Fusion Surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2019;44(18):1279-1286. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000003064

- Connor M, Briggs RG, Bonney PA, et al. Tobacco Use Is Associated With Increased 90-Day Readmission Among Patients Undergoing Surgery for Degenerative Spine Disease. Global Spine J. 2022;12(5):787-794. doi:10.1177/2192568220964032

- Ogunsola O, Linzey JR, Zaki MM, et al. Risk factors of emergency department visits following elective cervical and lumbar surgical procedures: a multi-institution analysis from the Michigan Spine Surgery Improvement Collaborative. J Neurosurg Spine. 2024;40(6):751-757. Published 2024 Mar 1. doi:10.3171/2024.1.SPINE23842

- Garcia RM, Khanna R, Dahdaleh NS, Cybulski G, Lam S, Smith ZA. Thirty-Day Readmission Risk Factors Following Single-Level Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion (TLIF) for 4992 Patients From the ACS-NSQIP Database. Global Spine J. 2017;7(3):220-226. doi:10.1177/2192568217694144

- Pugely AJ, Martin CT, Gao Y, Mendoza-Lattes S. Causes and risk factors for 30-day unplanned readmissions after lumbar spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39(9):761-768. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000000270

- Kang SS, Lee JS, Shin JK, Lee JM, Youn BH. The association between psychiatric factors and the development of chronic dysphagia after anterior cervical spine surgery. Eur Spine J. 2014;23(8):1694-1698. doi:10.1007/s00586-014-3281-3

- Schoell K, Wang C, D’Oro A, et al. Depression Increases the Rates of Neurological Complications and Failed Back Surgery Syndrome in Patients Undergoing Lumbar Spine Surgery. Clin Spine Surg. 2019;32(2):E78-E85. doi:10.1097/BSD.0000000000000730

- Weir S, Kuo TC, Samnaliev M, et al. Reoperation following lumbar spinal surgery: costs and outcomes in a UK population cohort study using the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) and Hospital Episode Statistics (HES). Eur Spine J. 2019;28(4):863-871. doi:10.1007/s00586-018-05871-5

- Xu HW, Fang XY, Chen H, et al. The Effects of Abdominal Obesity and Sagittal Imbalance on Sacroiliac Joint Pain After Lumbar Fusion. Pain Physician. 2024;27(1):59-67.

- Manoharan SR, Baker DK, Pasara SM, Ponce B, Deinlein D, Theiss SM. Thirty-day readmissions following adult spinal deformity surgery: an analysis of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database. Spine J. 2016;16(7):862-866. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2016.03.014

- Xu W, Ran B, Zhao J, Luo W, Gu R. Risk factors for failed back surgery syndrome following open posterior lumbar surgery for degenerative lumbar disease. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23(1):1141. Published 2022 Dec 31. doi:10.1186/s12891-022-06066-2

- Kim DK, Kim JY, Kim DY, Rhim SC, Yoon SH. Risk Factors of Proximal Junctional Kyphosis after Multilevel Fusion Surgery: More Than 2 Years Follow-Up Data. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2017;60(2):174-180. doi:10.3340/jkns.2016.0707.014

- Krzanowska E, Liberacka D, Przewłocki R, et al. The frequency and risk factors for surgery dissatisfaction in patients undergoing lumbar or cervical surgery for degenerative spinal conditions. Psychol Health Med. 2022;27(5):1084-1094. doi:10.1080/13548506.2020.1859562

- Ablin JN, Berman M, Aloush V, et al. Effect of Fibromyalgia Symptoms on Outcome of Spinal Surgery. Pain Med. 2017;18(4):773-780. doi:10.1093/pm/pnw232

- Kalakoti P, Volkmar AJ, Bedard NA, Eisenberg JM, Hendrickson NR, Pugely AJ. Preoperative Chronic Opioid Therapy Negatively Impacts Long-term Outcomes Following Cervical Fusion Surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2019;44(18):1279-1286. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000003064

- Masood R, LeRoy TE, Moverman MA, Feldman MW, Rogerson A, Salzler MJ. Functional Somatic Syndromes Are Associated With Varied Postoperative Outcomes and Increased Opioid Use After Spine Surgery: A Systematic Review. Global Spine J. 2024;14(5):1601-1608. doi:10.1177/21925682231217706

- Wu Q, Cui X, Guan LC, et al. Chronic pain after spine surgery: Insights into pathogenesis, new treatment, and preventive therapy. J Orthop Translat. 2023;42:147-159. Published 2023 Sep 30. doi:10.1016/j.jot.2023.07.003

- Bordoni B, Marelli F. Failed back surgery syndrome: review and new hypotheses. J Pain Res. 2016;9:17-22. Published 2016 Jan 12. doi:10.2147/JPR.S96754

- Freitas DG, Fonoff ET, Casamassima AC, et al. Pulsed radiofrequency of sympathetic lumbar plexus versus sympathetic block in the management of lower limb complex regional pain syndrome type 2. J Pain Relief. 2013;2(6):138.doi:10.4172/2167-0846.1000138.

- Baronio M, Baglivo M, Natalini G, et al. Genetic and physiological autonomic nervous system factors involved in failed back surgery syndrome: A review of the literature and report of nine cases treated with pulsed radiofrequency. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(13-S):e2020020. Published 2020 Nov 9. doi:10.23750/abm.v91i13-S.10533

- Goudman L, De Smedt A, Louis F, et al. The Link Between Spinal Cord Stimulation and the Parasympathetic Nervous System in Patients With Failed Back Surgery Syndrome. Neuromodulation. 2022;25(1):128-136. doi:10.1111/ner.13400